Women’s economic empowerment is the hot topic of the moment. There are relevant targets across at least seven of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Efforts to drive progress are being turbo-charged by the UN secretary general’s high-level panel on women’s economic empowerment.

The timing couldn’t be better: some serious rocket fuel is needed if governments are to deliver on their SDG promise to achieve women’s economic empowerment by 2030.

But as this agenda has moved out of the “gender ghetto” and into mainstream development practice, several myths have emerged. Here are five of the most common.

Myth 1: women’s economic contribution is limited when women are not employed

Globally, fewer women are in paid employment than men – our analysis of Gallup World Poll data from 138 countries shows that in 2015, an average of 36% of women were employed full time for an employer compared with 44% of men.

Yet women still make enormous economic contributions, including through unpaid care and domestic work. Among Gallup respondents surveyed in 46 countries in 2011, an average of 28% of women spent 3-5 hours a day on household work compared with just 6% of men.

These unpaid activities are critical to human wellbeing and maintaining the labour force, as well as in supporting the future workforce through childrearing. So although not directly remunerated, they have huge economic value.

However, recognising women’s unpaid care work is not enough to achieve women’s economic empowerment. Investment in care infrastructure is also needed to free women’s time to earn an income when they want to.

And where women’s care burden is alleviated by paid services, the priority is to improve the frequently low status, pay and working conditions of carers who are – you guessed it – overwhelmingly women and girls.

Myth 2: women’s economic participation is the same as women’s economic empowerment

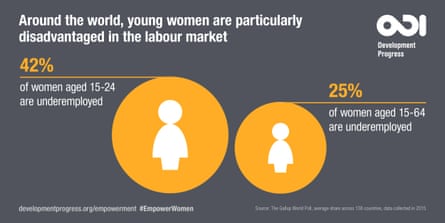

Getting women into the workforce is an important step. But empowerment is limited when women enter the labour market on unfavourable terms. This includes women’s engagement in exploitative, dangerous or stigmatised work as well as low pay and job insecurity.

Our analysis shows that having a good-quality job is “essential” or “very important” to men and women alike – on average, over 90% across 17 African and Middle Eastern countries surveyed in 2009 agreed. But in those countries, an average of only 14% of women that same year were engaged in full-time formal employment – a typical marker of a “good” job.

Tailored interventions can support women’s entry into better, more profitable and empowering work, such as investing in education and training, and removing legal restrictions to women’s employment and ability to set up businesses.

Better working conditions are also essential. For this, improving infrastructure and safety – both at the workplace and on the journey there – is critical, including for informal workers.

Myth 3: there is an automatic win-win between gender equality and wider development outcomes

There is overwhelming evidence that gender equality will help reach SDG targets on economic growth, family poverty reduction and human development. But it doesn’t always work the other way.

As a recent UN secretary general report confirms, many governments assume that faster growth will support gender equality, despite clear evidence to the contrary.

Therefore, focused effort is needed to ensure that economic empowerment delivers for women as well as families, societies and economies. Making a positive difference in the lives of half of the world’s population is a worthy objective in itself.

This means making gender equality an explicit concern across development policy, including labour and macroeconomic policy. And gender-responsive budgeting is a good way to assess the impacts of economic policy on equality and empowerment – positive examples of this include Morocco and Nepal.

Myth 4: what works for one group of women will work for another

Many of the barriers to women’s economic empowerment – such lack of access to property, assets and financial services, insufficient social protection and women’s unpaid care burdens – exist across countries. But women’s experiences of them differ vastly, depending on their particular demographic, economic or cultural context. Women shouldn’t be treated as a uniform group.

Evidence reviews confirm that while lessons should be learned from successful initiatives, direct replication is seldom entirely effective. Taking promising programmes to different contexts – including scaling up within the same country – requires careful tailoring to reflect different women’s experiences.

Myth 5: increasing women’s individual skills and aspirations is the main challenge

Support to individual women, such as training or increasing business management skills, has an important role in boosting their capacity to make the most of economic opportunities.

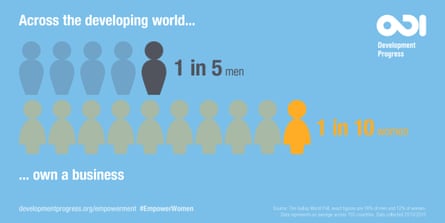

But this means little if the structural causes underpinning women’s lack of power are left intact. For example, our research shows that across 67 developing countries that Gallup surveyed in 2009, on average one in five men disagreed that women can hold any job that they are qualified for outside the home.

These kind of discriminatory attitudes limit women’s engagement in jobs they want – even when they are qualified for them. So in short, progress cannot be made without changing the wider cultural, economic and political factors that limit women’s economic empowerment.

This post was originally published by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).

Abigail Hunt is a research officer within ODI’s Development Progress project.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow @GuardianGDP on Twitter. Join the conversation with the hashtag #SheMatters.