It was a Sunday, so there was little to do but mark time and sniff glue. The shops were shut, the market half empty. With few people out and about, begging was unlikely to be a profitable enterprise.

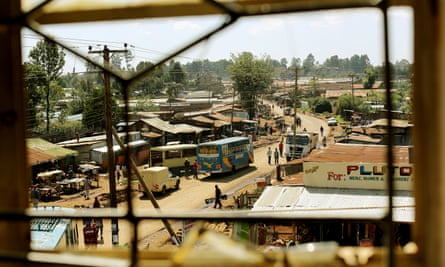

Instead, many of Eldoret’s street children had retreated to its central rubbish dump. Foetid and pestilential, this wasteland has long been a haven for the waifs of Kenya’s fifth city, the country’s highland capital and long-distance running heartland.

“California Barracks”, as it is known to the 700 homeless children and young adults who sleep there, usually provides something to eat: unwanted food dumped by local hotels or overripe fruit discarded by traders from the nearby market. It also offers a refuge, from society and from Eldoret’s police, who can rarely stomach the stench.

But not on that day, the penultimate Sunday of May. It was getting on for 4pm, the shadows lengthening on a chilly afternoon. Some of the children were asleep. Others sought solace in the cheap, hunger-suppressing fix of solvent abuse: boys inhaled glue from plastic containers clutched to their nostrils, girls in their early teens shared theirs with infants strapped to their backs.

In the warren of alleys above, the police advanced silently from three directions. Municipal officers, known as county askaris, carried cudgels and led the way; men from the Administrative Police, a feared state paramilitary unit, followed with rifles and teargas.

The inhabitants of California Barracks have grown accustomed to police brutality. Many there that Sunday had experienced it, like Samuel Asacha. A decade ago, when he was 15, he had one of his eyes gouged out by a particularly notorious officer. Or Shereen, then 10, and Shelagh, 14, both badly disfigured in 2014 when the same man, they say, threw acid in their face.

But the raid on California Barracks seemed different. This was not casual, workaday bullying but a carefully planned operation, systematic, meticulous – and one which city authorities have until now largely managed to cover up.

“They gave no warning,” said Eric Omondi, who at 20 is, like Samuel, one of the older members or “prefects” of California Barracks. “It was an ambush. Suddenly there were kids screaming, teargas being fired and officers shooting into the air.”

Advancing in a line, beating as they went, the police forced their victims towards the Sosiani river, which hugs the southern perimeter of the dump. Babies, girls, boys, disabled and able alike, were trampled down in merciless fashion.

None caught were spared, not even a 17-year-old called Mary, whom Omondi saw being beaten with such force that her baby fell headfirst from her arms onto the stony ground.

In a wheelchair after being run over by a county bulldozer clearing homeless shelters last year, Ronny, 16, had no chance of escape.

As blows rained down on his head and shoulders, he begged his tormenters to stop: “I told them ‘If you don’t stop, you are going to kill me.’ They replied: ‘We don’t care if we kill you. If killing you is what will scare others away, we will do it.”

By now some had managed to slip through the police lines, but others had been pushed to the riverbank. To escape the blows, they had no choice but to plunge into the Sosiani, then in full spate after heavy rains.

Although many did not know how to swim, prefects such as Omondi managed to help the stronger scramble for the far bank. But then the police fired teargas into the water. For the weaker, it was too much; they began to drown.

Omondi found the first body, belonging to his friend Francis Azmam – a boy of 13 known as Sudi, or “lucky” – caught in the roots of a tree overhanging the river. “He had multiple injuries on his head, chest and ribs, on his stomach and back,” he said.

Six children died in total and over the next two days the corpses of five more children would wash up downstream. The oldest, identified by social workers as Zakayo, was 16. The youngest, known as “Ndogo” or “Little”, was nine.

It was a horrific day for the street communities of Eldoret, but not the only one this year in which children have been killed.

Activists are convinced that the county government has embarked on a policy of trying to rid Eldoret of its street children population by killing them, or killing enough of them to force the others to flee.

The administration of Jackson Mandago, the county governor, denies that claim, presenting all police actions against street communities as a measured response to counter petty crime, blamed by some in the city on street children.

But activists point to a steadily escalating campaign that began in February 2015, when some 30 street children were bitten when police set dogs on them, according to the Ex-Street Children Community Organisation, a group of activists. The following October, the county authorities forcibly rounded up more than 100 street children, forced them into a lorry and dumped them 80 miles away in Malaba, a town on the Ugandan border. Most walked back to Eldoret.

The killings began after that, activists say. Ex-Street has documented the deaths of 14 minors so far this year, including three boys shot dead as they ran from police and three more whose bodies were found days after they had been arrested. At least five more are missing after being taken into custody and another two – 9-year-old Kevin Simuyu and David Kamau, eight, have not been seen since they were shot and wounded by police a fortnight after the raid on California Barracks.

Some believe that the attacks on street children are ethnically motivated. Most are not members of the county’s dominant Kalenjin community, the ethnic group of Kenya’s powerful deputy president, William Ruto.

The region around Eldoret has witnessed some of Kenya’s worst ethnic violence, often because of politically-manipulated tensions over land ownership. In 1991, Kalenjin warriors impaled foetuses ripped from dying Kikuyu women on spears which were then placed on the side of the road leading into Eldoret, as anger over Kikuyu encroachment into the ancestral lands exploded.

The violence reached a peak after a controversial election in 2007 saw Mwai Kibaki, a Kikuyu, re-elected president. At least 1,200 people were killed in the ensuing violence across Kenya, but the clashes were at their deadliest in and around Eldoret, where scores of Kikuyu women and children sheltering in a church were burned to death by Kalenjin fighters.

Although the Kalenjin and Kikuyu are now reconciled and share power (President Uhuru Kenyatta is a Kikuyu), some local politicians and clergymen say the attacks on street children appear to be part of a campaign of intimidation designed to force non-Kalenjins to leave Eldoret.

“If we don’t stop the killing of street families, this will escalate,” said Peter Chomba, a ruling party county legislator, who is Kikuyu. “If you look at what is happening, it is a pre-planned campaign. They profile professions drawn from certain communities and then attack them. What is happening is an attempt to claim this place for one community.”

Whatever the motive, few Kenyans would be particularly shocked to hear that the police were killing minors in Eldoret. Human rights groups have raised repeated concerns that extrajudicial killings have become part of police culture in Kenya. Reports of the execution of suspected Islamists, petty criminals and even human rights activists are becoming increasingly common.

Last week Kenya’s Daily Nation newspaper published a database documenting 122 police killings in the country so far this year. The database showed only two police killings in Eldoret this year and activists and some politicians say there has been a concerted effort to suppress the killings of street children in the city.

County legislators said that witnesses who had filmed the police operation at California Barracks from nearby buildings had been arrested and their mobile phones confiscated.

Benson Juma, one of directors of Ex-Street, was attacked by unidentified men who attempted to force him into a car days after leading more than a dozen witnesses to the killing of street children to the Guardian. He escaped, twice, thanks to the intervention of passersby. Juma has now fled Eldoret and is in hiding.

With Kenya set to go to the polls next year, he predicts the attacks on street children will only worsen. “It is turning into Brazil,” he said. “It is too much to bury and bury and bury our colleagues. It is too much – we may be forced to do something else to show the government that we are tired and fed up, to show them that we feel the pain.”