When I requested a copy of my police files from the Australian federal police I had no idea how far they would show the government had gone to track down my confidential sources for reporting on Australia’s asylum seeker policies.

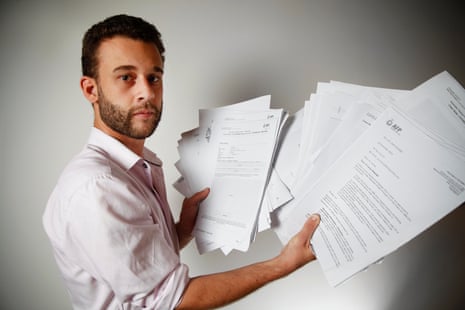

Sitting on my desk now are more than 200 pages of heavily redacted police files. Every journalist, in fact every Australian, has a right under the country’s privacy law to access personal information held on them by government agencies.

The files are made up of operational centre meeting minutes, file notes, interview records and a plan for an investigation the AFP undertook into one of my stories. Most concerning is what appears to be a list of suspects the AFP drew up, along with possible offences they believe they may have committed.

The documents show that during the course of an investigation into my sources for a story I had written, an AFP officer logged more than 800 electronic updates on the investigation file.

It’s a mosaic in document form of state surveillance of journalists by police. The files give an insight into the fragile state of journalism in Australia and the ease with which the police choose to take up these investigations because of poorly defined laws.

What’s behind the blacked-out redactions in the files is perhaps more alarming. The details of the steps the AFP took in the investigation, who they spoke to, what they planned to do, have all been withheld using a range of exemptions.

These files relate to one particular story I worked on. Just over 18 months ago I learnt that the federal police had taken on an investigation into what they considered to be an “unauthorised disclosure” of information to me. In April 2014 I reported for Guardian Australia that one of the vessels involved in Australia’s unlawful incursions into Indonesian waters, the Ocean Protector, had gone far deeper into Indonesian waters than the government had disclosed.

We put forward strong evidence that those on board the Ocean Protector knew they were entering Indonesian waters. Our findings contradicted what the government had said in a review of the incursions. We found the review itself was flawed – it had not even interviewed the vessel’s crew.

The public interest in the report about the Ocean Protector was significant. It disclosed more details about Australia’s unlawful entry into Indonesian waters. This took place to turn back an asylum seeker vessel under one of Australia’s most controversial asylum policies. We also published the first images of the Ocean Protector, which was the vessel later used to detain asylum seekers held at sea who became the subject of a high court challenge.

A short time after our report, the government backed down on a key point. It acknowledged that a customs officer in charge of the Ocean Protector did not respond to a crew member’s concerns that the vessel was charting a course into Indonesian waters.

None of that appears to have been taken into account from a policy perspective by the AFP. A short time later, it took a referral from the immigration department chief, Michael Pezzullo, to investigate who had leaked information to me, and prosecute them. On the files in front of me, there’s no evidence the AFP even paused to consider they were prying into the affairs of a journalist working on a public interest investigation.

It’s more than just an issue of AFP policy. It goes all the way to the enormous breadth of disclosure offences under Australian law, and the limited protection afforded to journalists.

There is a catch-all offence for public servants and contractors who make “unauthorised disclosures” of information to third parties. This offence is contained in section 70 of the Crimes Act. The first iteration of it actually appeared in the Queensland criminal code in 1899; at the time it was used to prohibit the disclosure of information about the state’s battery and fortifications.

Under this very broad offence the disclosure need not have caused harm to trigger investigation. There is no public interest defence. And certainly no defence for journalists. This is despite recommendations from the Australian Law Reform Commission that the offence be substantially wound back because it had “real concerns” that “disclosure of any information regardless of its nature of sensitivity” could be caught by it.

In the face of this offence, journalists are at great peril in their craft if they are taking on government agencies in serious public interest reporting. A plethora of other gag laws , such as the new Australian Border Force offence, could also be applied. The cumulative effect of these laws, in combination with the relatively easy access that police agencies have to journalists’ phone records, creates a hostile environment for reporters that is far more difficult to navigate than in countries such as the UK and the US.

Going after our sources is bad enough. But these offences have been crafted so broadly it would not be difficult for the police to at least make a case that a journalist has aided and abetted or acted as an accessory to a breach of one of these disclosure offences.

My police files have been heavily redacted by the AFP. I’m challenging their decision to deny me access to parts of my files with the privacy commissioner. I hope to be able to see more about the police surveillance that has taken place in the course of this investigation, and what the AFP has been doing with my personal information.

Many other journalists have been referred to the police for investigations of disclosure offences. Quite a few have been referred over their reporting on the government’s asylum seeker policies. They may find that requesting their own police files – at both the state and federal level – into exactly what steps the police are taking to investigate journalists working on public interest stories is an illuminating exercise.

In the UK privacy laws have been used to highlight the extent of surveillance on a list of “domestic extremists” that includes activists and journalists.

Ryan Shapiro in the US has used freedom of information laws to find out about FBI investigations of animal rights activists.

Perhaps it’s time for some of Australia’s most watched citizens to start doing the same.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion