Archaeologists have mapped a complete Roman city for the first time using ground-penetrating radar, revealing highly detailed images that they say could revolutionise our understanding of how such sites worked.

As well as a bath house, theatre, shops and several temples, the team from the universities of Cambridge and Ghent have discovered a large public monument of a kind never seen before, which may relate to the religious practices of the people who lived in the area before the Romans.

The detailed scanning of the town of Falerii Novi, just over 30 miles (50km) north of Rome, has uncovered the layout of the city’s water system, offering new clues to how it was planned and laid out.

In addition, experts say their research reveals evidence of a route around the outskirts of the city that was probably used as a religious processional way, and which was unlikely to have been uncovered by excavation alone.

“If you’re interested in the Roman empire, cities are absolutely critical because that is how the Roman empire worked – it ran everything through local cities,” said Martin Millett, a professor of classical archaeology at the University of Cambridge.

“Most of what we’ve got, apart from in sites like Pompeii, are little bits. You can dig a trench and get little insights, but it’s very difficult to see how they work as a whole. What remote sensing does is enable us to look at very large, complete sites, and to see in detail the structure of those cities without digging a hole.”

A walled city that was first occupied in 241BC, Falerii Novi survived until around AD700, but very few ruins remain visible above ground today. Unusually, the 30 hectare site – around half the size of Pompeii – has not been built over, allowing it to be scanned quickly by a series of antennae towed behind a quad bike. The architectural detail revealed by such a technique, such as at the city’s temple sites, is “amazing”, Millett said.

One notable discovery, he said, was the location of the city’s water system. Rather than running along the network of streets, the GPR showed it was laid out underneath the buildings before they were built, suggesting the city was highly planned “in a way that’s familiar today, but not expected, I think, in the third century BC”.

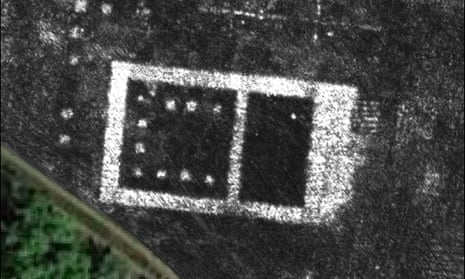

The team were also surprised to find a peripheral route circling the city lined with sacred buildings. One of these is a “big and spectacular” public monument, lined with colonnades and 60 metres in length, containing two smaller buildings with niches for statues or fountains – “and no one I’ve yet shown it to yet knows what it is”.

While the meaning and function of the building remains a mystery for now, Millett said it may be derived from the religious and cultural practices of the Faliscan people, who occupied this part of Italy before it was conquered by Rome.

“One of the big areas of discussion about the Roman empire is the way individual local communities worked, and how that interacted with the overall structures of Roman imperial power. What you’re seeing at Falerii, with this religious element to the landscape around the edge of the city, is probably the product of the local Faliscan identity. We’re seeing elements of their religious practice, we imagine, recreated within the Roman sphere.”

Millett and his team have already used GPR scanning on a number of smaller ancient sites, including at Aldborough in North Yorkshire, but now hope to use it at the ruins of larger cities. “As I wander around the Roman empire, I look at all kinds of places and think, ‘Wow, what we could do there’,” he said.

“It is exciting and now realistic to imagine GPR being used to survey a major city such as Miletus in Turkey, Nicopolis in Greece or Cyrene in Libya.

“We still have so much to learn about Roman urban life and this technology should open up unprecedented opportunities for decades to come.”

The team’s research is published in Antiquity.