Image by: joethegoatfarmer.com/

Note: In writing this post, I relied heavily on information presented in the book “Excellence Gaps in Education: Expanding Opportunities for Talented Students” by Jonathan Plucker and Scott Peters (Harvard Education Press, 2016). All page numbers referenced below can be attributed to this excellent resource. I highly recommend reading this book if you haven’t already!

“National norms” vs “local norms” in GT identification

When students are being identified for inclusion in a GT program, it is common for some kind of standardized academic, ability, or achievement test to be used. National norms take these standardized test results and compare and rank test takers in relation to one another using national standards. Then the raw scores of students from across the United States are used to establish national norms. In the case of gifted and talented students, identification criteria often uses norm-referenced cut scores — for example, students who score at 130 or higher on a given test, or score above the 95th percentile, may then be identified as being appropriate candidates for a GT program.

With local norms, however, students are compared against other students from their local educational setting, as opposed to a nationally-normed group, using some sort of assessment that is universally given to an entire grade level. With the usage of local norms, the standardization and validation of test scores is conducted within a local population and these community-based norm yielded scores are then used to represent the student scores of a school district and/or individual school.

The problem with using national norms

Gifted researchers are beginning to understand that using national norms for gifted identification is problematic because it makes the excellence gap — the disparity in the percent of students who reach advanced levels of academic performance based on income level, race, or ethnicity — worse.

Decisions made that are based on national norms tend to over-identify students in high-performing schools and under-identify those from low-performing schools. Additionally, students from black, Hispanic, Native American, and low-income families receive lower scores on nearly all tests of academic achievement, meaning cut scores based on a nationally-normed test will result in an under-representation of these students. This can turn into a ugly cycle. Students who do receive educational interventions through GT programming are presumed to make academic gains as a result; that is, the advanced students continue to advance. Meanwhile, the under-represented students are not receiving educational interventions through GT programming because they missed getting identified and therefore do not get the resultant increased academic achievement that would be expected. This only serves to widen the excellence gap. (See page 60 in “Excellence Gaps in Education”.)

The “gap”, once it appears in elementary school then continues as students move through middle school, high school, college and beyond. This leads to generations of black, Native American, Hispanic, and low-income students whose academic talents have not been developed. They have a greater likelihood of attending schools where access to educational opportunities and opportunities to learn may not have been developed to the degree that can be found at high-performing schools, which tend to have larger high-income and dominant-culture populations. Lower-performing schools tend to have fewer GT-identified students, meaning fewer talent development programs or access to high-level classes and GT programming and services. Fewer educational opportunities mean fewer chances to develop talent. (See pages 51, 60, and 93.)

Why using local norms could help

Teachers and administrators are going into their classrooms and schools trying to figure out which of their students are the most advanced in the class, the most talented in the school, the most likely to be under-challenged. These questions are answered by local comparisons, not national comparisons. If the criteria for identification are set at the 95th percentile of a national norm, some schools will have no gifted students while others may have a majority population of students that have been identified as gifted. But, if local norms are used, then the same percentage of students would be identified in every school, irrespective of the level of content mastery. For example, one school’s eighth grade GT math class might have kids working on Algebra II or trigonometry while in another school the 8th grade GT math class could be working on pre-algebra or Algebra I. In this manner, students who are the most under-challenged or not being well-served in their current educational setting would receive additional academic services and this would be happening in every school — not just the high-performing ones. (See pages 93-95.)

Want to do some more reading about the use of local norms?

The National Association for Gifted Children has a number of blog posts that discuss this:

“One such place is Montgomery County, Maryland, a large district in the Washington, D.C., area that’s made strides in diversifying the students served by its gifted education programs. By expanding the number of seats, universally screening every third grader, using more holistic identification criteria, and selecting students based on how they perform compared to kids at their school instead of the entire district (using “local norms”), administrators increased the proportion of black and Hispanic elementary-school participants from 23 percent in 2016 to 31 percent today . . . First, instead of creating a centralized gifted program in separate buildings or a single locale, base services in each school and use a combination of local and national norms to identify the high-potential students within each building. This gets around curricular and pedagogical worries by allowing educators to tailor their efforts to the top students in each school. Parents would be less concerned about who gets selected to go to the special school because rigorous academic services are provided right in the home school.” https://www.nagc.org/blog/diversify-gifted-education-dont-stop-there

“But such screening identifies advanced performers, not all students with advanced potential. That second number is much higher than the first, and probably a heck of a lot higher than people realize. Using local norms helps in this regard—and I’m about the fullest-throated proponent of local norms you’ll find—but it still doesn’t close opportunity gaps. The opportunity gap I’m most worried about is access to high-quality advanced learning with frontloading to ensure students are ready to capitalize on those opportunities. That’s the gap that vexes us, and that’s also where the authors’ third recommendation comes into play.” https://www.nagc.org/blog/every-american-school-has-talented-students-its-time-start-acting-we-believe

“Ability grouping? “Not in our district, people don’t believe in it.” Universal screening? “Too expensive.” Use of local norms? “Politically tricky. Pass.” Teacher and administrator training? “Preparation programs will never do it, and we don’t have the bandwidth at the district level.” And the kicker, which is so common that I’ve become numb to it: “This is an important topic, but my urban/rural district doesn’t have any bright kids” (a comment I’ve heard from principals, superintendents, and even a state school chief).” https://www.nagc.org/blog/washington-suburbs-praiseworthy-plan-narrow-excellence-gap

“To reverse these trends, the authors call for universal screening and other solutions to make for a more equitable identification, such as using local norms and multiple criteria, to identify talent. The study also notes the importance of a diverse teaching corps to support these efforts.” https://www.nagc.org/about-nagc/media/press-releases/there-gifted-gap

“Now we need to focus on moving a new bill that will increase equity and access through universal screening, evaluation using multiple criteria, and eligibility for services based on local norms. Additionally, the bill recognizes the importance of professional development and accountability.” https://www.nagc.org/blog/creating-change

“High-achieving children in poverty and from minority groups are 250 percent less likely to be identified for, and served in, gifted and talented programs in schools.

SOLUTION: Equitable Identification

All children deserve fair identification strategies. Screening all children, using multiple measures, and benchmarking against local norms increases fairness and the diversity of children identifies and served in gifted programs while keeping standards high.” https://www.nagc.org/build-understanding-provide-solutions-inspire-action

“The second marker is a bill awaiting signature by Governor Jay Inslee of Washington State. Senate Bill 6362 requires that school districts establish state of the art identification methods that promote equity of access for all students, particularly those who live in poverty or are English Language Learners. The bill calls for the use of multiple objective criteria; criteria benchmarked on local norms; screening and assessment in native languages or non-verbal screening and assessments, and clear guidance and best practices from the state Office of Public Instruction.” https://www.nagc.org/blog/giftedness-valued-recognized-nurtured

“The new bill – SB 6508 and HB 2927, Equity in Highly Capable Identification – will require the Superintendent of Public Instruction to confirm that each school district has policies and procedures in place to identify highly capable children and that these screening practices be nondiscriminatory and prioritize equitable identification of students from low-income families.

The legislation will require universal screening of all students at distinct times in their educational journeys. Districts must use multiple criteria that include multiple pathways for students to qualify for HCP and should base decisions against local norms for that district. Testing must occur during the school day and in the student’s home school, meaning no student will ever be missed because he or she could not travel to a test site on a weekend.” https://www.nagc.org/blog/close-gap-washington%E2%80%99s-gifted-children-deserve-better

Want to better understand disparities in your district?

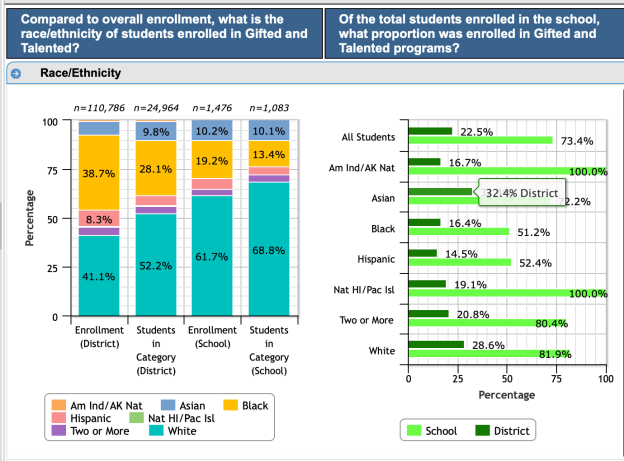

The U.S. Department of Education has conducted the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) to collect data on key education and civil rights issues in America’s public schools since 1968. It collects a variety of information including student enrollment and educational programs and services, much of which is disaggregated by race/ethnicity, sex, limited English proficiency, and disability. The most recent data (for the 2015/16 school year) was just released in April of 2018 and can be accessed here: https://ocrdata.ed.gov

You can go to the site and look up the most recent data available for your school or district, look at detailed data tables, access data analysis tools, and view special reports for schools and districts.

If you are curious about an individual school, go to the school and district search option, search the school name, and then click on the “pathways to college and career readiness” on the left sidebar.

That will allow you to see a breakdown of the school’s overall enrollment and also show you how many students are enrolled in GT (and how proportionally they are represented).

After that, click “gifted/talented enrollment” on the right sidebar.

That will give even more detailed information that compares that particular school’s data to the district’s data.

Once you’ve looked at one school, just repeat the process for any other school you are interested in to see how they compare.

Pingback: Using local norms for more equitable representation in gifted and talented programs | BCPS GT CAC