America began saying goodbye to a civil rights icon on Saturday, the first of six days of gatherings honoring the life of the late Congressman John Lewis.

The remembrances began in Lewis’ hometown of Troy, the small Alabama city about 200 miles southwest of Atlanta where Lewis was born and raised. By evening they shifted to Selma, the site of one of the bloodiest — and most important — moments of the civil rights movement in which Lewis played a central role.

Lewis, 80, died July 17 after a battle with pancreatic cancer. He’ll be buried Thursday in Atlanta’s South-View Cemetery, but not before memorials in five cities and a funeral service at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church. Lewis’ body will also lie in state in three capitol buildings: in Montgomery, Ala., Washington, D.C. and Atlanta.

Saturday’s first ceremony began as a relatively understated, family-focused affair and ended on a festive note as gospel great Dottie Peoples brought the crowd to its feet. Several hundred people were on hand at Troy University’s Trojan Arena for the socially distanced memorial, which included tributes from several of Lewis’ siblings, local officials and Baptist leaders.

Credit: Ryon Horne / Ryon.Horne@ajc.com and Tyson Horne / Tyson.Horne@ajc.com

Henry Grant Lewis, a brother, said the congressman “gravitated toward the least of us.” He’d feed the hungry and homeless on Thanksgiving Day, drop by his nephew’s 5th grade class and once surprised a young Troy resident who portrayed Lewis in his Black history class.

“He worked a lifetime to help others and made the world a better place in which to live,” he added.

Troy Mayor Jason Reeves noted that the head of the Alabama State Troopers, which in March 1965 ferociously beat Lewis and other voting rights marchers on Bloody Sunday, is now led by a Black man.

Col. Charles Ward, Reeves said, leads the force “not because of the color of his skin, but because of the content of his character and the ability that he has. That’s what John Lewis did for Troy, for Pike County, for the United States and for the world.”

Socially distanced events

COVID-19 gave the proceedings a surreal feel.

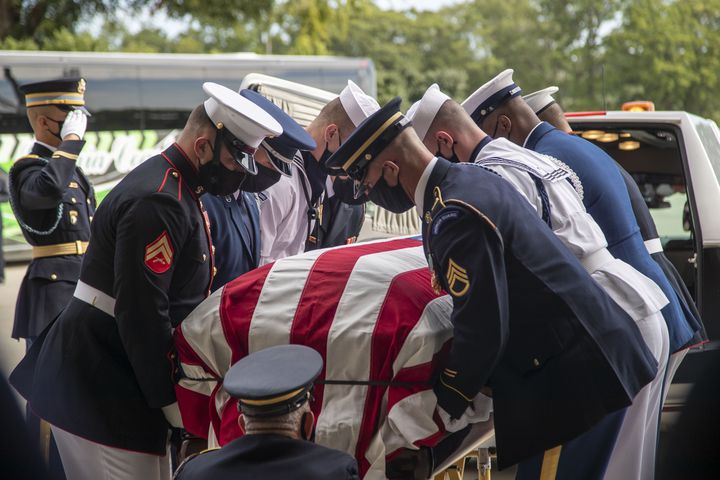

Lewis’ flag-draped casket was carried into Troy University’s arena by eight military pallbearers, all wearing black masks. Visitors sat six feet apart from one another on folding chairs.

Several of this week’s events are closed to the public because of the pandemic. Lewis’ family urged people not to travel for the events and instead show their support online and at home by tying blue or purple ribbons on their front doors. (Blue is the color of Lewis’ fraternity; purple is the ribbon color for pancreatic cancer.)

Of those who chose to attend Saturday’s event at Trojan Arena, many were extended family. Lewis’ niece, Mary Lewis-Jones, estimated there were more than 100 relatives at the memorial service.

“To come back here, and see Troy embrace him the way it has, really means a lot,” said Lewis-Jones, who now lives in Fort Lauderdale.

Pamela Lee felt compelled to drive nearly three hours, alone, from Mariana, Fla., to attend the memorial service in Troy. Lee said she told herself, “I’ve got to be there,” after hearing the news about Lewis’ death.

“I have a very big heart for freedom fighters. And John Lewis and Dr. King were true freedom fighters,” she said Saturday.

Lee, born two years before Bloody Sunday, thought of her grandparents, who lived in Alabama their whole lives, as she waited for the service to begin.

“His legacy is going to live on forever,” she said.

‘The Boy from Troy'

The day was steeped in symbolism from Lewis’ life.

Troy University helped spark Lewis’ civil rights activism. In 1958, the teenage Lewis applied to what was then the all-white Troy State, joining African American students around the country who were organizing to force the question of the “Brown vs. Board of Education” ruling.

Lewis never heard back, but the school’s silence prompted him to reach out to an inspiring preacher he’d heard on the radio: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. King sent him a bus ticket, and shortly after the two met, King bestowed the nickname “The Boy from Troy.” It was a name Lewis carried the rest of his life, and the theme of Saturday’s memorial.

A second service was held later at Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma. The church was where roughly 600 civil rights protesters, including a 25-year-old Lewis, gathered on March 7, 1965 for a planned march to Montgomery.

The violent response by Alabama State Troopers roughly six blocks away, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, galvanized the nation and paved the way for Congress’ passage of the Voting Rights Act months later.

On Sunday morning, Lewis will cross the bridge one final time, accompanied by a military honor guard. Many of those escorting the congressman’s coffin, according to Troy’s mayor, will be Alabama State Troopers.

Staff writers Tia Mitchell and Ernie Suggs contributed to this article.

Sunday’s events

The theme is “The Final Crossing.” In the late morning, a military honor guard will accompany Lewis across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge for the last time. The processional will depart from Brown Chapel at 11 a.m. EDT.

At 3 p.m., he’ll arrive at the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery. Lewis will lie in state there until 8 p.m.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/I6QQBFIHQJGZREOLT3LF44VUZI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/3RDHGIFTTPTTMWKP5PCYO55YZM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/WI3J6JHQLWN7KQFRMLPZRLAGNI.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/P7RHOXOLJ3GJOYQJO4NMZCJBCE.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/U3LXNWCC5AESUUN37UUDGCRVQY.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/ESEXCRJMD6ZW35ZPFJNAP7XODU.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/H4MKGDWO3NTHCQY4NI2QNA44HM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/256QML5PAUKHUVIAQI6GUSS5DQ.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/VX5DVGQQGMUEEDO3VYKF2D64K4.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/VXOT5IOEMOE5D6BARYDAITUB7U.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/LHB3C7N3ZHKGLJCV7IW2JRSLRQ.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/KXEYPVPMVL3SD57PFLNURXTVNU.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/Z7QBMBVTWGCZDZ36SZQTQIBQXY.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/E7ATWWACAHELK2NDPL3BB4HEIQ.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/IJMDT3XXY2RK5IEM2VUGHAX7VE.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/7GW2K5JK6D3PYFWO6KCIBACMBU.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/3426UN6GAT24IP77EXZIVHMRRY.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/EPNOTTCDXCUAI4VEKUA6DIDY5E.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/2TUIPH75FD27SJBMQNDQDQ4XAM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/ZEV7DLWM3SSITSYXONBP5QSOZM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/WI7PEZZXAM7IZVL3IMS33HRHXM.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/QGXZ6CER2LGDMOYCRC3DJ4CNAQ.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/7AGZVKE7FJHZOP2HTL55GO2JFI.JPG)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/KURU67ON5FYCJVKASBMX2ZZN2Y.JPG)