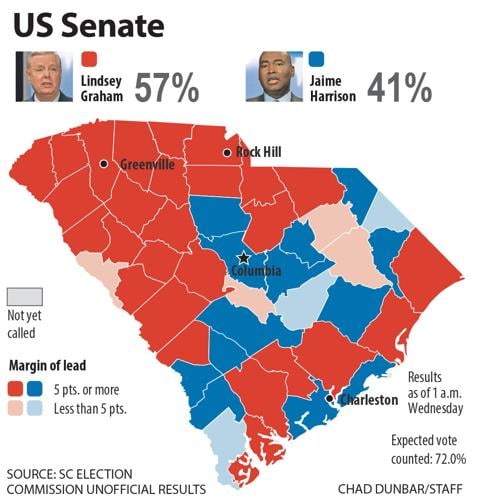

COLUMBIA — Republican incumbent Lindsey Graham survived the most daunting threat of his political career Tuesday, comfortably defeating well-funded Democratic challenger Jaime Harrison to win reelection and secure another six-year term representing South Carolina in the U.S. Senate.

The Associated Press declared Graham the winner shortly before 10 p.m, just three hours after the polls closed.

With 72 percent of precincts reporting, Graham held a commanding 15 percentage point lead, according to the AP.

In a victory speech to supporters, Graham thanked South Carolina for keeping faith in him, touting his victory as a signal to Democratic donors around the country that the Palmetto State will stay solidly Republican for years to come.

"To those who have been following the race from afar: I hope you got the message," Graham said. "I will do everything I can to stop the radical agenda coming from Nancy Pelosi."

Graham praised Harrison for "an incredible campaign," including his record-breaking fundraising — though he attributed much of that to liberal opposition to himself.

"You're a good father, you're a good husband, you're a good man," Graham said of his opponent.

Democratic Senate candidate Jamie Harrison speaks at a watch party after losing the Senate race in Columbia, S.C. Tuesday, Nov. 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Richard Shiro)

Conceding a few miles away from Graham's celebration in Columbia, Harrison delivered an aspirational concession speech that reiterated his vision for a "new South" and repeatedly praised the staffers who drove his record breaking campaign.

“You can all hold your heads up high, because you beat all of the odds,” Harrison told a crowd of a few dozen campaign aides who gathered on a frigid night at the Hunter-Gatherer Brewery in Columbia.

Harrison congratulated Graham on winning reelection and publicly wished the Seneca Republican "will maintain the spirit of cooperation he is known for" as he returns to the Senate.

He spoke of his campaign as a movement that sought to remove the barriers, such as poor infrastructure and shoddy internet access, that stand between South Carolinians and a better life.

"We proved that a new South is rising," Harrison said. "Tonight only slowed us down."

U.S. Rep. Jim Clyburn, who won re-election Tuesday, told the crowd Harrison would not go away after a campaign that broke U.S. Senate fundraising records.

"Jaime did not get elected to the United States Senate tonight. But Jaime is a real winner," the Columbia Democrat said. "He is going to live his life committed to this country, to this state and our human race, and I want to congratulate him for a great race."

After entering the race as the clear favorite in a historically conservative state that has not elected a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in more than two decades, Graham went on to face a stronger challenge from Harrison than many political observers initially expected en route to his fourth term.

The contest emerged as one of the most closely watched in the country during the final few months of the race as polls showed Harrison narrowing Graham’s lead, and in some cases even overtaking him, in what had long been considered a reliably Republican state.

But Graham successfully unified conservatives in the home stretch, buoyed by a Supreme Court confirmation that he attributed with helping remind Republican-leaning voters about the policy consequences at stake in the race.

Harrison harnessed national outrage from Democrats toward Graham over his transformation from one of President Donald Trump’s fiercest critics during the 2016 campaign to one of his closest congressional allies in recent years to raise more money than any U.S. Senate candidate in history.

By Election Day, Harrison had raised well over $100 million, a staggering sum that allowed him to blanket South Carolina airwaves for months with ads that both introduced himself to voters in a positive light and attacked Graham as a political shape-shifter more concerned with his own influence than the well-being of the state.

But Graham, while unable to match Harrison’s fundraising juggernaut, built a formidable campaign operation of his own and was boosted by a late flood of outside spending from Republican groups swooping in to defend him.

Republicans remained confident that no amount of spending from Harrison would be enough to overcome South Carolina's conservative tilt.

As chairman of the Senate Judiciary committee, Graham touted his work confirming more than 200 conservative judicial nominees in recent years — including, most prominently, Trump’s latest Supreme Court pick, Amy Coney Barrett, just eight days before the election.

Graham also leaned on his friendly relationship with Trump, who remains popular with many Republican voters in South Carolina, as well as his conservative credentials on issues like taxes, abortion and the military.

Republican colleagues lauded Graham’s ability to help South Carolina in Washington, pointing to him as the most influential member of the state’s congressional delegation whose seniority they said would bolster the state for years to come.

Though Harrison was the former S.C. Democratic Party chairman and had spent much of his adult life working in politics, this race represented his first run for public office.

The Democratic challenger highlighted his rags-to-riches personal story, rising from an impoverished childhood as the son of a single mother in Orangeburg to attend Yale and Georgetown Law School before going on to work in the highest echelons of American politics on Capitol Hill.

In the closing weeks of the race, Graham also began to remind South Carolina voters of his own humble upbringing, including being raised in his family’s bar in Central and caring for his sister after both of their parents died when he was 21.

To avoid alienating moderate voters, Harrison declined to back some of the more progressive proposals from members of his own party, like single-payer government funded health care and a sweeping Green New Deal to drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Instead, Harrison emphasized his preference to build on the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, by adding a public option, and to take a more piecemeal approach to tackling the threat of climate change.

He talked openly about his experiences combatting racism as a Black man in America and the historic symbolism of his candidacy, hoping to mobilize the African American voters who comprise almost a third of South Carolina’s electorate.

In a bid to split the conservative vote, Harrison also spent some of his campaign funds in the last month of the race elevating the profile of Constitution Party candidate Bill Bledsoe.

Though Bledsoe ended his campaign and endorsed Graham in early October, that decision came too late to remove his name from the ballot. Harrison began running ads and sending out mailers to Republicans warning that Bledsoe was “too conservative” and “too pro-Trump,” neglecting to mention that Bledsoe had backed Graham.

In the end, Bledsoe was only garnering less than 2 percent of the vote with a majority percent of precincts reporting, far too little to drag down Graham enough for Harrison to overcome him. Graham's lead also appeared to be considerably higher than would be needed for Bledsoe to even make it close.

Like elections up and down the ballot nationwide, the race between Harrison and Graham required novel approaches to campaigning due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Harrison, who has preexisting health conditions that he feared could present complications if he contracted the virus, spent the past eight months of the race campaigning almost exclusively online through virtual forums, emerging to hold drive-in rallies only towards the end of the contest.

Graham, on the other hand, continued attending more in-person events, though generally with smaller and more distanced crowds than would typically be expected for a race of this magnitude.

The reduction of in-person campaigning placed even more importance on other forms of getting their messages out, leading to an onslaught of television and radio ads, mailers, billboards and other promotional methods from both the candidates and outside groups supporting them.