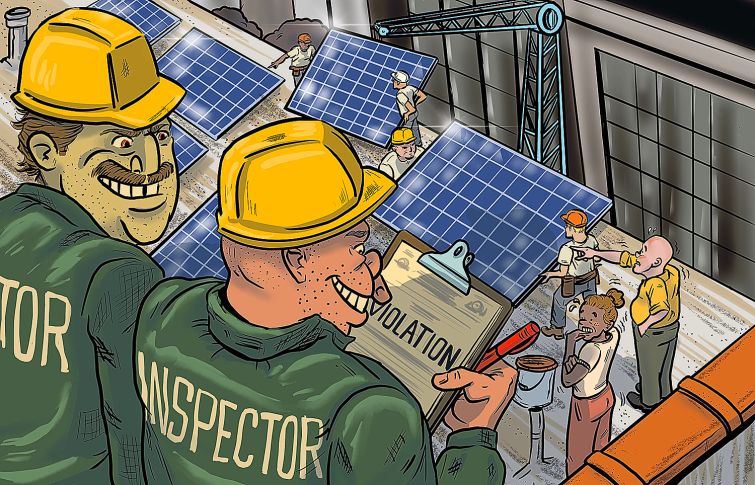

Emission Omission: Is New York’s Big Carbon Reduction Law for Buildings on Track?

New York’s rollout of Local Law 97 — a first-in-the-nation set of rules aimed at shrinking buildings’ carbon footprint — has been full of holes so far. Will that change under Eric Adams?

By Rebecca Baird-Remba January 19, 2022 2:54 pm

reprints

Nearly three years after then-Mayor Bill de Blasio signed a groundbreaking law aimed at forcing building owners to reduce their carbon footprint, the New York real estate industry and many of its observers claim that implementation of the environmental legislation has been slow and that the city office responsible for enforcing the law doesn’t have the funding or staff to do so. Some charge that the city itself isn’t on track to comply with its own rules.

Local Law 97, passed by the City Council in March 2019, requires owners of buildings that are 25,000 square feet or larger to begin reducing their greenhouse gas emissions starting in 2024 and to meet lower benchmarks every five years until 2050.

The law created a new office within the Department of Buildings — dubbed the Office of Building Energy and Emissions Performance — that would handle enforcement of the new emissions standards. Gina Bocra, the chief sustainability officer at the DOB, leads the six-person office. Her team oversees the complex rulemaking process for the law, processing applications from owners who want a variance because they can’t meet the law’s requirements, and deciding penalties for owners who don’t comply with the emissions standards. They will also, ultimately, be responsible for monitoring buildings’ emissions — largely via reports submitted by landlords — and for auditing specific properties to ensure that they are reporting their energy use truthfully.

“Too few people are working on this in DOB,” said Adam Roberts, the director of policy for the Architects Institute of America, one of the groups that advocated for the law. “The city has not devoted enough resources to the Department of Buildings. If we don’t have enough staff at the Department of Buildings, landlords are going to be able to lie [about emissions] and get away with it.”

A spokesman for DOB said that its “Sustainability Unit and Office of Building Energy and Emissions Performance (OBEEP) are effectively implementing and enforcing Local Law 97.”

Roberts said that he had heard from his members — many of whom are architects employed by the city government — that the city does not have a concrete plan for its own buildings to meet the emission standards set by Local Law 97.

“City buildings are not on track to comply,” Roberts said. “One of the first things the mayor [de Blasio] did during the pandemic was choose to stop public works. Your school is going to open a year later, as is your library and your police station. So the city buildings are also a year behind on complying.”

In response, a spokesman for the Department of Citywide Administrative Services, which is overseeing the retrofits for city properties, said that the city had spent $715 million on 2,700 energy efficiency projects in city buildings since 2014. However, sources familiar with the agency say that it has struggled to stay on track with Local 97 work, amid significant budget cuts and a staff shortage. And the team responsible for the energy retrofits faces more potential budget and staff cuts under the Adams administration.

He added that even new public buildings that are under construction or in the pipeline don’t seem to take Local Law 97 into account.

“There also has not been a real cohesive effort to make new or existing city buildings comply,” Roberts said. “And that’s really unfortunate, because the city is the one that provides services for the most vulnerable. It does not seem like they are undertaking any massive campaign to retrofit buildings. If the city isn’t planning for 2024 and 2030, they’re not going to be able to comply. We’ve asked many times and they are not going to be on the path to compliance.”

Supporters of Local Law 97 say it will be hard to convince private-sector landlords to retrofit their buildings and reduce their energy usage if the city isn’t planning to do the same.

“And if the city isn’t complying and they’re championing the law, how do we expect everyone else to take it seriously?” asked Roberts. “And the economic benefits and jobs won’t come about if there’s no compliance. And the quality of our homes and offices continues to decline compared to other cities in America.”

The city has announced plans to buy electricity from a Canadian hydropower transmission line, the Champlain Hudson Power Express, in order to power its own buildings. The hydroelectricity project, one of two set to bring “clean” electricity to the five boroughs by 2025, is being built by Blackstone and Hydro-Québec.

One of de Blasio’s last acts in office, on Dec. 22, 2021, was to sign an executive order with a Local Law 97 implementation plan for city agencies. The press release from the mayor’s office promised to “invest in cost-effective emissions reductions opportunities,” reduce energy consumption at city buildings 20 percent by 2030, and expand solar installations at city properties “to generate more than 110 million kilowatt-hours of solar energy per year by 2025, enough to power 26,000 New York City homes.” The order also required city agencies to develop plans for reducing their specific carbon footprints as part of their capital plans.

“I think there’s a bigger question about how serious this effort was and will be,” Roberts said. “It was done in the last days of the administration, received no press coverage, and wasn’t even floated with the multitude of groups who advocated for the law. This is the first time I have even heard about it, and, based on conversations with my colleagues at other organizations, I don’t think they are aware that the former mayor made this announcement.”

A City Hall spokesman said that Mayor Eric Adams “supports the goals of Local Law 97 and encourages building owners to use the NYC Accelerator program, which provides assistance to building owners, including retrofit advice, help securing PACE financing, and help applying for available incentive programs. The mayor acknowledges that in order to reach our environmental goals, the city needs to reduce the cost of retrofits and upgrades, and avoid overly punitive fines that do nothing to advance our sustainability goals. That is why he has supported city subsidies to assist property owners in need with the cost of retrofitting and called for significant investment in retrofitting the city’s own buildings as part of a broader strategy to ensure NYC is a national leader in reducing carbon emissions and in creating a green economy.”

Meanwhile, the Real Estate Board of New York slammed the city for its glacial rollout of programs that are supposed to be implemented as part of the Climate Mobilization Act, which was the package of laws passed in conjunction with Local Law 97.

Alex Shapanka, a vice president of policy for the real estate trade organization, said that the rollout of the Property Assessed Clean Energy financing program — commonly known as PACE — was delayed by 18 months to two years after climate legislation passed. PACE loans, which are also offered by the state’s energy agency, are a common tool landlords use to help finance the upfront costs of making energy efficiency upgrades.

“It was approved by the city but the first loans were not granted until the end of 2021,” Shapanka said. “It took them almost two years to get the program up and running and then allow applicants to receive money. They were talking about this program being available without actually conferring the benefits.”

He pointed out that developers of new commercial buildings couldn’t apply for the financing until mid-2021, and the city still has not finalized rulemaking and guidelines for new commercial applicants.

Shapanka also noted that the city had delayed the release of a number of reports required by Local Law 97, including a carbon trading study — released 10 months late in November 2021 — as well as reports on the city’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 and 2019. The city has also pushed back the release of its long-term energy plan — which was supposed to include benchmarks for decarbonizing its energy grid — another six months, until the middle of 2022.

Several large landlords are also still waiting for major pieces of guidance from the DOB on the law, sources told Commercial Observer. DOB officials have told them the rulemaking process may not be complete until 2023 or 2024. The buildings department has also been slow to notify the owners of roughly 90 buildings who applied for a variance to the law regarding whether or not they are eligible for a reduction in emissions standards. Major commercial owners and their staff — many of whom are facing hundreds of millions of dollars in necessary renovations and upgrades — have struggled to plan for the law’s upcoming deadlines in 2024 and 2030 without the DOB guidance.

In response, DOB spokesman Andrew Rudansky noted that “Local Law 97 requires that certain rules be in effect by January 1, 2023. The Department is working on that rulemaking process already. The Department will also continue to work to reduce uncertainty for owners and will be publishing guidance in both rules and bulletins throughout 2022.”

As for the variances, Rudansky said in a statement that “every applicant that submitted for an adjustment to their LL97 Limits prior to the deadlines in 2021 has heard back from the Department, including many who have received detailed objections from the Department regarding their application. Some of the applicants have not responded yet to the Department’s initial objections and request for required documentation that was missing from their applications. Incomplete applications cannot be reviewed.”

Anthony Malkin, the president and CEO of Empire State Realty Trust, is the only landlord serving on the main advisory board responsible for Local Law 97 implementation and declined to be interviewed for this story.

Alex Heil, the vice president of research for the nonpartisan, nonprofit Citizens Budget Commission, argued that the law wouldn’t be effective until landlords had more concrete guidelines from the DOB.

“This is a complex piece of legislation that is going to have a big impact on the sector that produces 70 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions for the city,” he said. “It’s not like anybody who owns real estate is going to do this a couple months before. The more certainty you provide, the more effective these policies will be.”

Pete Sikora of advocacy group New York Communities for Change, who was heavily involved in advocating for the law and now serves on the city’s advisory board, defended the slow rulemaking and implementation process.

“Do they want a poorly thought out, slapdash rulemaking process?” he asked. “The industry is saying things are moving too slowly but there’s a contradiction there. Either you want it to be fine, well-thought-out categorizations of those different kinds of uses and occupancies, or you want it to be fast.”

He added that the advisory board, along with the DOB and the city’s Department of Finance, were working on more fine-grained ways of evaluating commercial buildings. For example, the law, as written, treats all office buildings the same. Sikora said the city’s guidance would create different emissions standards for office buildings with more energy-intensive uses, such as data centers.

He also felt that the DOB’s energy efficiency office had not received the necessary staff and funding.

“One thing the city did not do well was allocate enough staff lines to that office,” Sikora said. “But they did allocate $10 million a year to the accelerator to guide building owners for advice.”

However, his greatest fear is that Adams would water down the law, either by lowering the financial penalties for landlords or by not giving the DOB enough staff and funding to enforce it.

“When Eric Adams’ spokespeople talk about the law, they’ve been using the industry’s lingo, and saying, ‘We agree with the law but the structure of the law is unfair, these penalties are unfair.’ We want to see the Adams administration continue the good work of this issue, an issue that New York is at the forefront of. Eric Adams should not listen to the real estate industry and weaken this law or cut the penalties.”

He added that it’s “certainly the wrong thing to do substantively and morally, and a big mistake politically. It’s our hope that Adams listens to his better angels rather than the real estate devils whispering in his ear.”