Vast expanses of lush green fields are multiplying in the Arizona desert, forming agricultural empires nourished with billions of gallons of groundwater in the otherwise parched landscape.

Arizona’s groundwater levels are plummeting in many areas. The problem is especially severe in unregulated rural areas where there are no limits on pumping. The water levels in more than 2,000 wells have dropped more than 100 feet since they were first drilled. The number of newly constructed wells is accelerating, and wells are being drilled deeper and hitting water at lower levels.

This free-for-all is draining away the water that homeowners also depend on, leaving some with dry wells.

As the groundwater is depleted, Arizona is suffering permanent losses that may not be recouped for thousands of years. These underground reserves that were laid down over millennia represent the only water that many rural communities can count on as the desert Southwest becomes hotter and drier with climate change.

Unfettered pumping has taken a toll on the state’s aquifers for many years, but just as experts are calling for Arizona to develop plans to save its ancient underground water, pumping is accelerating and the problems are getting much worse.

Big farming companies owned by out-of-state investors and foreign agriculture giants have descended on rural Arizona and snapped up farmland in areas where there is no limit on pumping.

Buying property from struggling small farms and homeowners, they’ve drilled wells a thousand feet deep or more, often spending more than half a million dollars per well to irrigate tens of thousands of acres of hay, corn, pistachios and other thirsty crops, with the expectation that they’ll soon be raking in profits.

In unregulated rural areas where water tables are dropping, homeowners and politicians are calling for the state to step in to halt well-drilling, or create new rules to limit pumping.

In these predominantly conservative communities, where the ethos is to take care of yourself and be wary of government regulation, prominent local officials are suggesting a moratorium on drilling, or the formation of new managed areas where drilling would be restricted.

Even urban areas of the state where protections exist are facing major challenges. Years of drought, rapid growth and cutbacks in Colorado River water are increasing the pressures on groundwater in areas that fall under state regulation.

In an unprecedented examination of the state’s groundwater, The Arizona Republic analyzed water-level data for more than 33,000 wells throughout Arizona, including some records going back more than 100 years, and nearly 250,000 well-drilling records.

The investigation found the water levels in nearly one in four wells in Arizona’s groundwater monitoring program have dropped more than 100 feet since they were drilled, a loss that scientists and water experts say is likely irrecoverable.

Nearly half of the wells with five or more measurements have dropped more than 50 feet at some point since record-keeping began. And that’s only in a limited number of wells whose owners agreed to be voluntarily monitored.

Arizona doesn't require meters on wells in many areas, meaning no one really knows how much water is being pumped out.

Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said the lack of metering is a major hole in Arizona's groundwater laws. He said his department has proposed mandatory water-use reporting by well owners in unregulated areas. That data would enable the agency to see precisely how much water is being taken out of aquifers.

"We need that pumping data," he said.

Many of the industrial farms have located themselves in the rural areas that have already seen the largest water-level drops over time.

Arizona water consultant Marvin Glotfelty said it's difficult to determine how much the corporate farms have additionally dropped the aquifers without building complex groundwater models that can cost as much as $50,000.

"In our firm, what we are having farmers come and ask us is, 'Is there enough water for X period of time?'" Glotfelty said. "And if we say, 'OK, there's enough water to last 50 years, and it's going to result in several hundred feet of water level drawdown,' we give them that answer and they'll go forward with their farm."

These farmlands, which are forming circular islands of emerald green in the desert, are swiftly draining aquifers. People who live nearby are increasingly living in fear that their water may soon run out.

Some wells have already gone dry, leaving families struggling to cope with the costs.

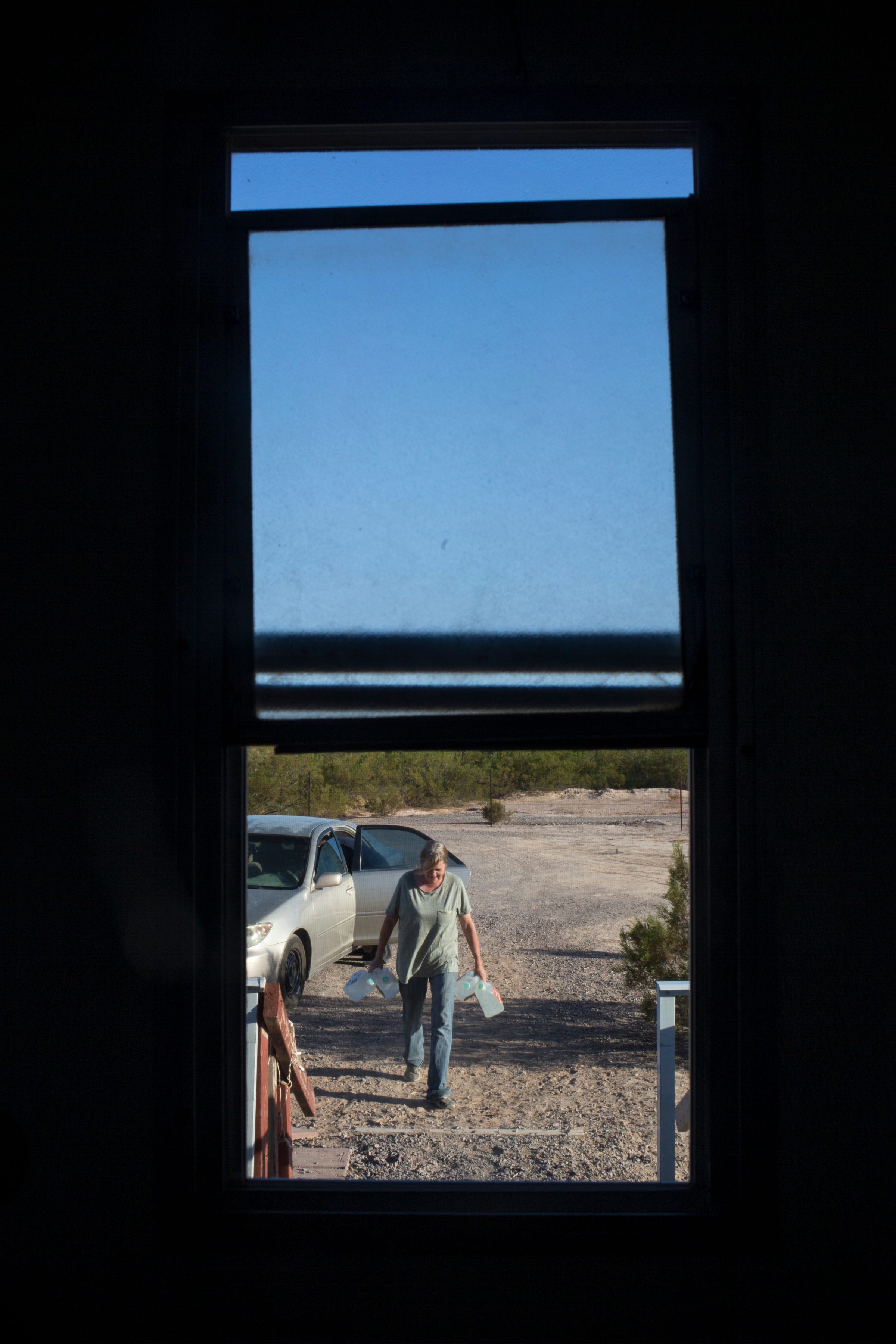

Rodney Hayes’ well went dry in July, as his wife, Nancy Blevins, was washing the dishes. Their pump burned up when the water level dropped, and the two, who live near a giant Saudi Arabian hay farm in Vicksburg, had to look for water elsewhere.

They hauled water, 100 one-gallon bottles at a time, from a friend who lent her tap. They dreamed about getting water back on for even a few hours a day.

“At least we could take showers without going to friends’ houses or truck stops or, you know, pouring water over each other,” he said.

In November, they finally managed to buy a new pump and got water running at their home again. But there's no telling how long it might last.

Regions where pumping isn’t restricted — from Mohave and La Paz counties in the west to Cochise County in the southeast — have become hotspots where groundwater is being quickly depleted.

While the water tables drop year after year, the political system seems paralyzed and incapable of limiting pumping or helping residents who are saddled with the costs.

So the status quo stays in place: Large farms continue to pump out vast quantities of water. Homeowners continue to bear the costs. And this irreplaceable supply of water continues to drop.

Long-term problem getting worse

The largest drops in groundwater levels have occurred over decades, in valleys where farms have been drawing on aquifers for 70 years or more.

Some areas of the state have dropped so much that the water likely won’t naturally recover in our lifetimes. The McMullen Valley, surrounding Salome and Wenden in the desert about 40 miles northeast of Quartzsite, has seen the average water level in state-monitored wells drop by 184 feet since the 1950s. The average well in the Gila Bend basin has dropped by 162 feet.

In Pinal County, in the Maricopa-Stanfield basin around Maricopa, monitored wells have declined by 125 feet since the 1950s. In the area around Vicksburg, where the 10,000-acre Saudi hay farming operation opened five years ago to ship hay back home, the average water level has dropped 120 feet since the '50s.

In the “active management areas” that were created by Arizona’s landmark Groundwater Management Act in 1980, average water levels have stopped falling and recovered somewhat after Colorado River water was brought by canal in the 1980s and 1990s

But in rural areas without regulation, average water levels across all monitored wells in the state have dived in recent years and are threatening to surpass all-time lows hit in the mid-1980s.

State officials estimate that 40% of the water that's used in Arizona is groundwater.

Robert Glennon, a water expert and law professor at the University of Arizona, said the sharp declines in groundwater levels are alarming.

“Those are big numbers, and it’s probably not reversible,” Glennon said. "A 50 or 100-foot drop is a big drop. And that makes it much more expensive for everyone to use what water there is."

In those unregulated rural areas of the state, the overuse of water is getting worse. Large commercial farms are ramping up, drilling wells and pumping billions of gallons from stressed aquifers every year.

"They go to the place where there’s no regulation, because they can just suck the hell out of the water and leave," Glennon said.

With water tables falling, state drilling records show that more and more wells are being drilled, and they’re being drilled deeper. The wells in the overstressed Willcox basin were drilled 358 feet deeper on average in 2018 than they were in 2010. Nearby in San Simon, wells were 211 feet deeper.

In the Wellton-Mohawk basin, which straddles Interstate 8 on the way to Yuma, the average well was drilled 741 feet deeper in 2018 than in 2010. In the Hualapai Valley around Kingman, where large corporate farms have spurred calls for regulation, wells were drilled an average of 280 feet deeper than eight years ago.

There are no state or national standards that determine how big a drop in a well is problematic. The only standard Arizona has for wells is a rule inside managed areas that a well cannot be built if it will drop a neighbor’s well by more than 10 feet over five years. Applying that standard to all monitored wells statewide reveals that 20 percent of wells dropped more than that during at least one five-year period.

In many areas, there are only rough estimates of how much extractable freshwater remains underground, and it’s unclear how much longer overpumping could continue until aquifers approach a point where the remaining water is too deep to pump economically.

“My concern is really about the future,” said Jay Famiglietti, who leads the Global Institute for Water Security at the University of Saskatchewan. “How long can it really go on before, in the case of Arizona, the water is gone?”

Famiglietti, a former NASA scientist, has used measurements from satellites to study groundwater worldwide, and has found that many of the world’s large aquifers are declining.

Groundwater levels have been falling in many areas across the United States, and the problem has been especially pronounced in farming areas of the West, from the productive nut and fruit orchards of California’s Central Valley to the cornfields atop the Ogallala Aquifer in the High Plains.

The plunging water levels in unregulated parts of Arizona parallel similar declines in other Western states. But the state's water data shows that the problem has been worsening with the arrival of industrial farms and investors.

And people who live near the expanding farmlands are paying a heavy price.

'I don't feel safe'

For companies growing crops like alfalfa and corn, Arizona offers economical land, a sunny climate with several growing seasons, and cheap, readily available water from wells. As these farms pump more water, the collective costs are passed on to neighbors and homeowners. While the water tables decline beneath their homes, wells have been going dry.

Several years ago, as alfalfa farms expanded into virgin desert and fallow farmland around the town of Salome, Mary Goodman’s well suddenly dried up.

Goodman, a 71-year-old retired nurse, and her husband, Bill, a retired mechanic, spent $16,000 of their retirement money drilling a new 680-foot-deep well. Now they worry about how long the water will last.

I don’t think I should be forced to sell my home just to feel safe. But I don’t feel safe.

“Half of me feels like we ought to just sell out now, if we can get a good price, and get the heck out of here before we run out of water,” Goodman said. “The other half says, 'you love it here. You’ve worked for 20 years to build this place up.' So I don’t think I should be forced to sell my home just to feel safe. But I don’t feel safe.”

Near the Goodmans' house, where there are two dirt runways for Bill’s aviation hobby, new industrial wells have been drilled beside Highway 60. Goodman said all the pumping in McMullen Valley is gradually taking a toll on their well.

“The only comforting thought is by the time it goes dry, we'll probably be dead — if that's a comfort,” she said.

She said it’s upsetting and scary to see the place where she planned to live out the rest of her life being drained of its water, and nobody doing anything about it.

“I think it looks very grim if something isn’t done to start protecting the water in this area,” Goodman said. “There need to be some laws put into place to protect the water.”

In her town and elsewhere in the state, calls for regulation have been growing. People have been clamoring for politicians and water officials to act to safeguard groundwater before it disappears.

HAVE A FAILING WELL OR A DRY WELL? We want to hear from you

More than 50 miles south of Goodman's home, in the remote desert straddling the Maricopa-Yuma County line, a ghost town stands as a reminder of the potential consequences of unchecked groundwater pumping.

An abandoned hotel, with its windows boarded up, lies at the base of a rocky hill. This was once a popular hot spring resort, an oasis for travelers to stop and rest.

The Agua Caliente hot spring has a history that goes back well before Arizona became a state, said Matt Bischoff, a historian who has studied the area.

A Spanish mission was built there in 1774 and in the 1800s the springs became a resort for people traveling by horse and stagecoach along the trail that followed the Gila River.

In the 1860s, noted author John Ross Browne wrote about a visit in the book "Adventures in the Apache Country." He wrote: "An abundant supply of water flows ... We had a glorious bath in the springs next morning, which completely set us up after the dust and grit of the journey."

The 22-room hotel was built next to the hot springs in 1897, Bischoff said. During World War II, troops trained nearby at Camp Hyder and swam in the springs.

Now, if you drive down Old Agua Caliente Road in Hyder, you’ll find “No Trespassing” signs posted on the shuttered hotel. Near it, the remnants of wooden buildings are splintering and decaying in the sun.

The road near the Agua Caliente ghost town is lined with dead mesquite trees. Their roots no longer reach the water, and their branches have been transformed into brittle charcoal-gray skeletons.

The hotel shut down after the war, when the completion of the highway allowed drivers to bypass Agua Caliente. But it was groundwater pumping from farms, Bischoff said, that drew down the water table and dried up the springs.

"The overpumping is what killed it off completely," Bischoff said.

Arizona politics offers little hope for fix

Nearly 40 years ago, Arizona adopted a landmark law regulating groundwater in Phoenix, Tucson, and populated, mostly urban areas. The law left the rest of the state without rules limiting drilling or pumping.

“Outside of the active management areas, you can drill a well of any size, and any place you want, and pump as much as you like,” said Kathleen Ferris, the former Department of Water Resources director who helped draft the Groundwater Management Act.

But there’s only been one addition to regulated areas since the groundwater law was approved, and that expansion occurred in 1981. Five recent efforts to limit groundwater pumping in three different counties — Cochise, La Paz and Mohave — have failed.

There is little the Arizona Department of Water Resources can do under the law to limit groundwater pumping.

“So the only thing that they can do outside of (managed areas) is to require that wells be drilled in conformance with well construction standards and by a licensed well driller and that they'd be registered with the department,” said Ferris, now a senior research fellow at Arizona State University’s Kyl Center for Water Policy.

The Department of Water Resources can also create new managed areas of the state, either by declaring the area itself or establishing one if enough landowners sign petitions. But three recent efforts to create new managed areas, one in San Simon near Willcox and two efforts requested by leaders in Mohave County, were rejected by the state.

State officials said that in those cases water levels weren’t dropping rapidly enough to create a new managed area and they couldn’t take into account potential future increases in pumping. ADWR director Buschatzke ruled the state would have to wait to see even larger declines before putting in new regulations that would create an "irrigation non-expansion area" that would freeze new irrigation.

"I'm definitely constrained by the law, I only have the authority to do certain things," Buschatzke said. "We can only look at today and yesterday in terms of decline rates."

In 2017, Buschatzke's department proposed new legislation that would give the agency the ability to project water availability decades into the future when making decisions on limiting irrigation.

The package of new rules also called for metering of wells outside managed areas. Buschatzke said the department couldn't get any legislators to take up the bills.

"That's our challenge, how to build up enough support among the stakeholders that we can get something passed at the Legislature," he said.

In addition, the calls for regulation led to a surge in well-drilling around Willcox. Completed wells surged from 43 wells in 2010 to 123 wells in 2015.

State lawmakers have declined to establish new regulations.

Legislators declined to wade into a 2015 effort by community leaders in Willcox for voluntary regulation to limit groundwater pumping there, which ultimately failed. Requests to limit wells from large corporate farms in La Paz County and prevent new irrigated farms in Mohave County were met by the Legislature with an allocation of $100,000 to create study groups to examine aquifer levels there.

Mark my words. It's just the beginning.

It’s unclear how many wells across the state have gone dry in recent years, because neither state officials nor county officials have been systematically tracking reports of dry wells — even though they’ve been getting regular complaints.

Bruce Babbitt, the former governor who signed the 1980 Groundwater Management Act into law, is calling for the state to regulate groundwater in rural areas and give county officials a leading role. In a speech in October, Babbitt said problems are mounting in unregulated rural areas.

“What we're seeing is a rise of industrial agriculture on a scale that we've never seen in this state, from New York hedge funds, from Nevada investors, from Middle Eastern investors,” Babbitt said. “That industrial agriculture is just the beginning, I submit to you, of a new era of intense, unprecedented demand."

He pointed to the arrival of big corporate farms in Mohave, La Paz and Cochise counties.

“Mark my words. It's just the beginning,” Babbitt said.

Four decades ago, the political situation was much different. When the Arizona Legislature passed the nation’s first comprehensive groundwater management law, there was a genuine crisis. A ruling by the Arizona Supreme Court had upended the state’s water rules four years earlier and the state faced the threat of losing Central Arizona Project water if it did nothing.

“We had leadership in the Legislature that believed it had to happen and had a governor who also believed it had to happen,” Ferris said.

Gov. Doug Ducey didn't respond to repeated requests for comment on Arizona's water issues. Ducey's Water Augmentation, Innovation and Conservation Council has a committee on rural groundwater outside of regulated areas. That committee is headed by Rep. Gail Griffin who at least five times in the past four years has tried to loosen groundwater regulations. She also did not respond to requests for comment.

Ferris said for real change to happen now, the Legislature must get involved again. But unless they do, Arizona’s paralyzed system continues the status quo, with homeowners bearing the costs of failing wells and large farms continuing to pump with no limitations.

“Unfortunately the people that have control of the status quo don’t want it to change,” Ferris said.

Draining fossil water

In the dusty fields near the dry bed of the Gila River in Hyder, not far from the Agua Caliente ghost town, drilling rigs are boring deep into the ground.

Companies have been buying land to lease to hay growers, and they’re putting in new wells more than 1,500 feet deep, creating Arizona’s next agricultural frontier for industrial farms.

Mark Skousen runs a second-generation family farm near the abandoned hot spring in Hyder. When his father bought the land and drilled a well in 1957, the water gushed out of the ground. At that time, the Agua Caliente hot spring was still flowing.

In the early 1960s, when Skousen was a boy, another farmer drilled wells at a farm near the hot spring. When they started pumping, the water quit flowing out of the ground and the hot spring died.

“The water table's been dropping steady since then,” Skousen said.

Some of his wells no longer produce enough water and he has had to reduce the number of acres he farms.

In the long term, the water losses may be irreversible in many rural communities. Much of the groundwater that’s flowing to farmland accumulated underground thousands of years ago. As it’s pumped out, the aquifers are suffering a hollowing-out that the rains won’t replenish for centuries to come.

In a few areas of the state, aquifers have been replenished by years of “banking” imported water from the Colorado River, and there, groundwater levels have risen.

But even in “active management areas” around Phoenix, Tucson and Pinal County, where aquifers have benefited from decades of regulation, there still have been significant declines in some areas. In more than half the subbasins in managed areas, average water levels have declined since the 1980s even with restrictions on groundwater pumping and additional CAP water.

Arizona faces its first-ever mandatory cuts in Colorado River water next year under an agreement that will shrink the amount of water that’s available to replenish aquifers in urban areas. And in the long-term, with climate change projected to put growing strains on water supplies from rivers, Phoenix and other cities plan to potentially pump more groundwater.

Groundwater also feeds desert streams and rivers, and decades of heavy pumping has left them with diminished flows. The future of remaining rivers, from the San Pedro to the Verde, hangs in the balance.

Overpumping can also drive up costs.

At deeper levels, groundwater can contain higher levels of contaminants, which can require expensive treatment. And the deeper the water table falls, the more energy costs increase to pump the water out.

If nothing changes, Ferris said, “either the groundwater runs out, or it becomes too expensive to pump, or its quality is such that it’s too expensive to treat to use.”

Environmental coverage on azcentral.com and in The Arizona Republic is supported by a grant from the Nina Mason Pulliam Charitable Trust. Follow The Republic environmental reporting team at environment.azcentral.com and @azcenvironment on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.