There is certainly no shortage of one thing in the world, and that's a lack of goodwill to all men. And women. And children. If it isn't Russia introducing laws against homosexuality, then it's Saudi Arabia resisting the idea that women should drive cars. If it isn't Burma, spoilt for choice, decade after decade, as to which ethnicity to cleanse, then it's a bunch of African countries extolling female genital mutilation.

And outrageous as these horrors are, even the countries that we in the UK see as our natural allies, and consider as sharing our values, are hardly perfect. The US clings to capital punishment, thwarted only by a lack of the chemicals necessary to kill. Australia stands against gay marriage. Israel continues to favour the needs of settlers over established populations. Europe continues to harbour virulent antisemitism.

Britain is hardly without problems either. Hardly a day goes by without some giant, discriminatory insult provoking heated indignation. If it isn't a forgotten X Factor winner blithely sharing his homophobia, then it is a little-known university rule-making body being blasted for promoting gender segregation. If it isn't some obscure politician demanding that all Europeans should be sent back to Europe, then it's some woeful cliche of a lawyer bemoaning the horrors of sexually predatory children.

Our own transgressions against human rights may seem minor compared to those being perpetrated abroad, and our condemnations of them satisfyingly uncompromising. But it is surely helpful to remind ourselves that our own anti-discriminatory consensus is an extremely recent development. Living adults remember when their sexuality was illegal, when women had the right to complete an undergraduate course, but not to receive a degree. While people continue to count racism against them as part of their daily experience, their parents can remember when this wasn't even against the law. People who expected to die without being brought to account for their sexual crimes against children, as Jimmy Savile did, are belatedly seeing the inside of a court of law.

Sometimes, bearing in mind the novelty of our enlightenment, angry anti-discrimination Britons can seem like evangelically disapproving former smokers, which is never a good look. But that's not important. What is important is to recognise that once a breakthrough is made, change can be fast and profound. Transformations in British attitudes haven't even been generational. Individuals have moved from being sexist, racist and homophobic to realising they were wrong to harbour such prejudices.

It is crucial to remember that people can learn and change, quickly and en masse. One of the sad things that followed Nelson Mandela's death was the sight of people on the left recounting the past pro-apartheid beliefs of others, real and imagined. The anti-apartheid movement existed to change minds. Lingering suspicions that some of the most spectacular converts are only pretending undermines and belittles the movement's most necessary and hard-won achievements.

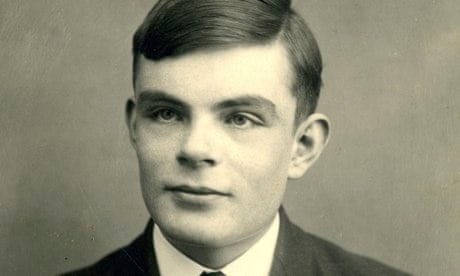

Also, it is useful, this recent history of vast social change in the west. Not only does it remind us that people who don't think as we do now are no less human and fallible than we are. It also offers a handy primer on how to achieve change. The human rights movement was born out of violence – the violence of the second world war in general and of the Holocaust in particular. In simple terms, there was, on the one hand, a realisation that the war could not have been won without brave and resourceful working-class people, without brave and resourceful women, without brave and resourceful gays – Alan Turing, Enigma code-breaker having been fully "pardoned" for being gay only this year. On the other, it offered the most abject lesson the world has yet known in the genocidal atrocities that bigotry can unleash.

In Britain, some postwar change came quickly, such as the establishment of the welfare state. Other postwar changes, such as the strengthening of the trade union movement, have already been quashed. Some change – in attitudes to women, to racism, to homophobia – needed concerted effort from activists. What underpins it all, however, is the idea of human rights, an idea that has done so much to make the world a fairer place, but continues to be misrepresented and maligned.

Human rights are often mocked as imaginary. "How can a baby, born of nature, have inherent 'rights', any more than a newborn rabbit?" goes one argument. But human rights are not imaginary. They're conceptual. They rest on a single idea – that all humans have a common need for certain conditions if they are to flourish as productive members of society, and that all humans have a responsibility to ensure that everyone attains and maintains those rights. (The second part of the covenant is more often overlooked than the first, it's true.)

It is no accident that the human rights that require no infrastructural investment made such progress in the 1980s and 90s. Those were times, after all, when rights that came with a large bill – the right to shelter, the right to earn a living, and so on – were being eroded. You could argue that the left timidly retreated into identity politics during that time of Rout By Neo-liberalism. You could also argue that it chose its battles pragmatically – those it could win.

The human rights that come without the need for direct financial investment are also the simplest. If some people can go about their business without their skin colour being an issue, that's how it should be for all humans. If some adults are allowed to conduct their consensual sexual lives as they wish to, then all should. If some adults are encouraged to utilise their skills and intelligence fully, then all should. And so on.

It's significant, of course, that these ideas of common rights flourished in Britain at a time when religious belief was in decline. For many, these days, religious belief is seen as one of the greatest bars to the spread of human rights. (Although the worship in some quarters of economic inequality and the power it confers to the few gives religion a run for its money.) It looks simple: if some people are allowed to practise their religious beliefs, then all should be able to. How easy that is to say. How hard it is to implement. Multiculturalism, really, can be seen as an attempt to put that simple, treacherous idea into practice. It can also be seen as an aspect of identity politics that has fared less well than others. With good reason.

For human rights to flourish, religious rights have to come second to them. We are all human. We are not all of the same religion, or religious at all. One cannot protect religious rights if they are used as a reason to abuse human rights, human equalities, as so often they are. Britain may not be able to export its new-found anti-discriminatory zeal to the rest of the world with much ease. But Britain is in a good position to start working out a framework whereby people with diverse beliefs can live together without conflict, safe in the knowledge that the religious beliefs of all who respect human rights will be respected in turn. People need to answer on Earth to our fellow humans. We can square things with our God, if we have one, when and if that day arrives. Compliments of the season, whatever that means to you.