By Jenny Miglus, Preservation/Special Collections Librarian

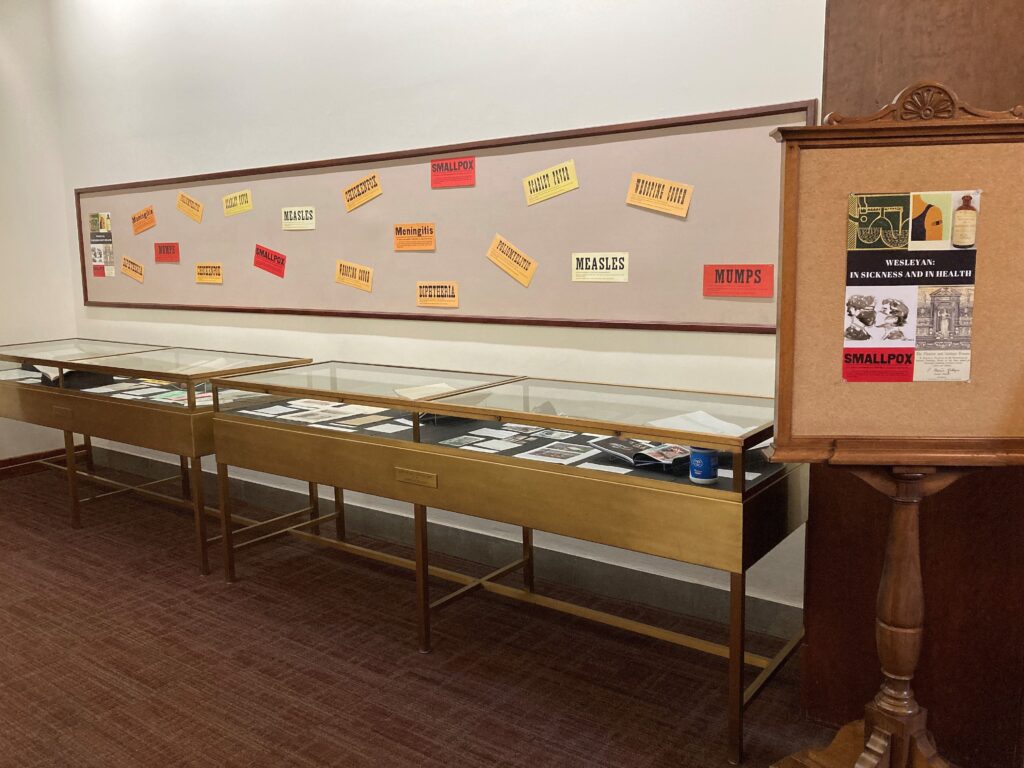

A new exhibit, Wesleyan: In Sickness and in Health, is on display in Olin Library. “Why this topic?” you say, “Haven’t we heard enough about disease lately?” Good point. We are sick of hearing about people getting sick. On the other hand, people throughout history have worked to understand, cure and prevent disease, and they continue to do so. We can focus on this. Wesleyan has had its share of sickness, but it has also contributed significantly to treatment and prevention. Sickness – – Health; two sides of the same (human) coin. Let’s flip it and see what comes up.

Up through the end of the 19th century the causes of disease were mysterious and treatment was often ineffective. At Wesleyan, the records show that there were several outbreaks of typhoid, and at least one of smallpox. There was no provision for health services at that time and students simply recovered in their dorm rooms or went home, if they were able to. In the early 20th century Wesleyan had an arrangement with Middlesex Hospital to care for ailing students. In spite of this, seven students died during the 1918 influenza epidemic. The generosity of George Davison finally allowed the construction of the Davison Infirmary in 1936. A patient room from that time looks homey and comfortable.

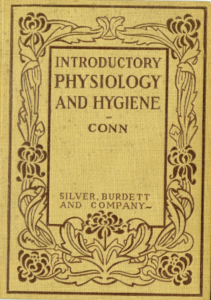

In the 20th century researchers identified the causes of many diseases and developed effective ways to treat them. Along with improved diagnosis and treatment, the discipline of public health emerged in the 19th century and blossomed in the early 20th. This led to improved sanitation and better test facilities for disease-causing agents in food and in people. Wesleyan’s Professor Herbert W. Conn was the first to trace an outbreak of typhoid on campus to oysters that were grown in polluted waters. Professor Conn also started a lab on the grounds of Wesleyan to test for bacterial disease. He published a book for dairymen about sanitation in milk production and a book for school children about good hygiene.

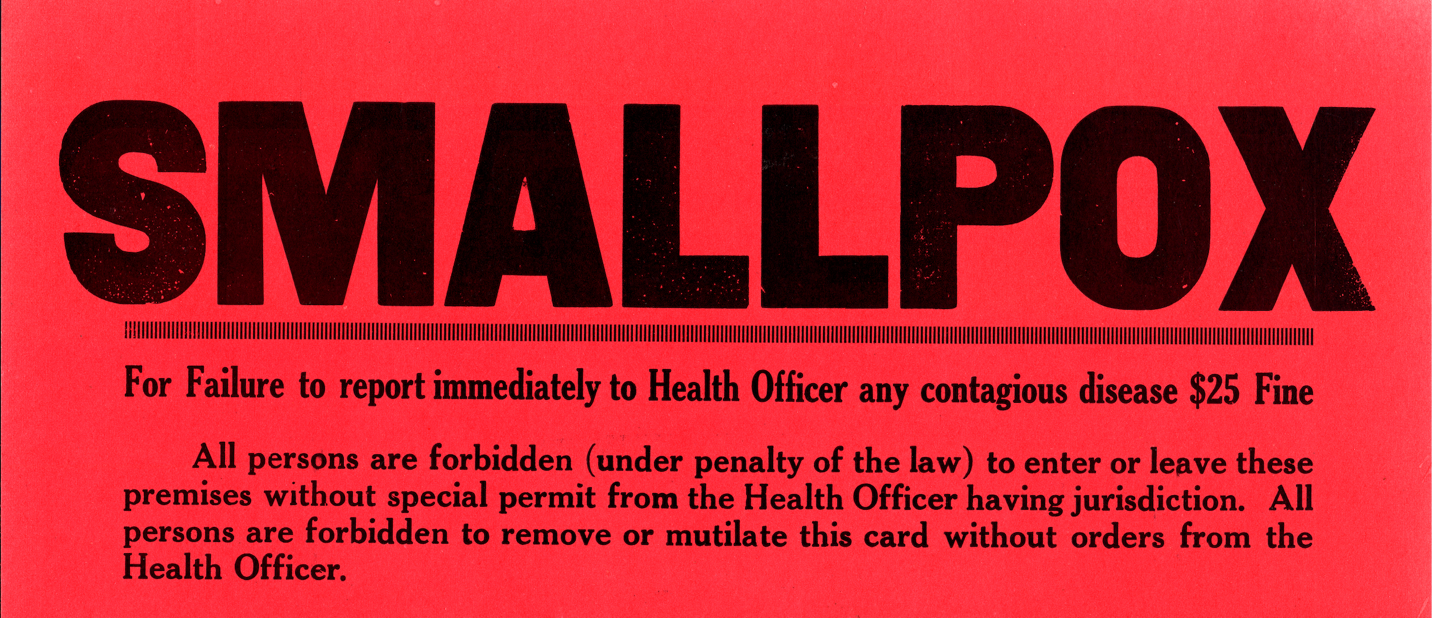

Unlike typhoid and cholera which are caused by bacteria, smallpox is caused by a virus. Historically, protection from smallpox could be obtained through “variolation”, although why this worked was not understood at the time. During variolation, infected matter from a patient is inserted under the skin or dry matter breathed in by a healthy individual. This was dangerous because you were being exposed to the active virus, but mortality was only 10% of what it was if you contracted the disease directly.

Vaccines are different from variolation because they use a modified or different virus to induce immunity and are far less dangerous. Edward Jenner first used this technique using cow pox, a viral disease related to, but different from smallpox, to vaccinate against smallpox.

Vaccines have rid the world of smallpox and are keeping diseases such as measles, polio and chickenpox at bay.

Covid-19 has been a reminder that we have not conquered disease, even though we have much better tools to detect and manage it. The biggest obstacles to global health today are misinformation, climate change, and racial, social and financial inequalities.

Medicine and biomedical research work at the microscopic or individual level and are reactive. Clinicians and researchers confront a disease and try to eradicate it. Public Health operates at the level of community and is proactive. Practitioners in this field work to prevent disease in the first place. We need both of these strong disciplines to continue to improve health outcomes. However this century calls for a global approach to health. We have to reduce environmental inequalities, also inequalities of financial and social resources. We need to come up with new ways to communicate with one another. How can we teach people to accept differences and to disagree respectfully? If the focus of the 19 century was on microorganisms, the 20th on social and medical systems, then the 21st should be on the total human organism and its whole-earth ecosystem. The scope is huge, but all of our lives depend on it.

To learn more, visit the exhibit on the main floor of Olin Library, east side, just down the hall from Special Collections & Archives.