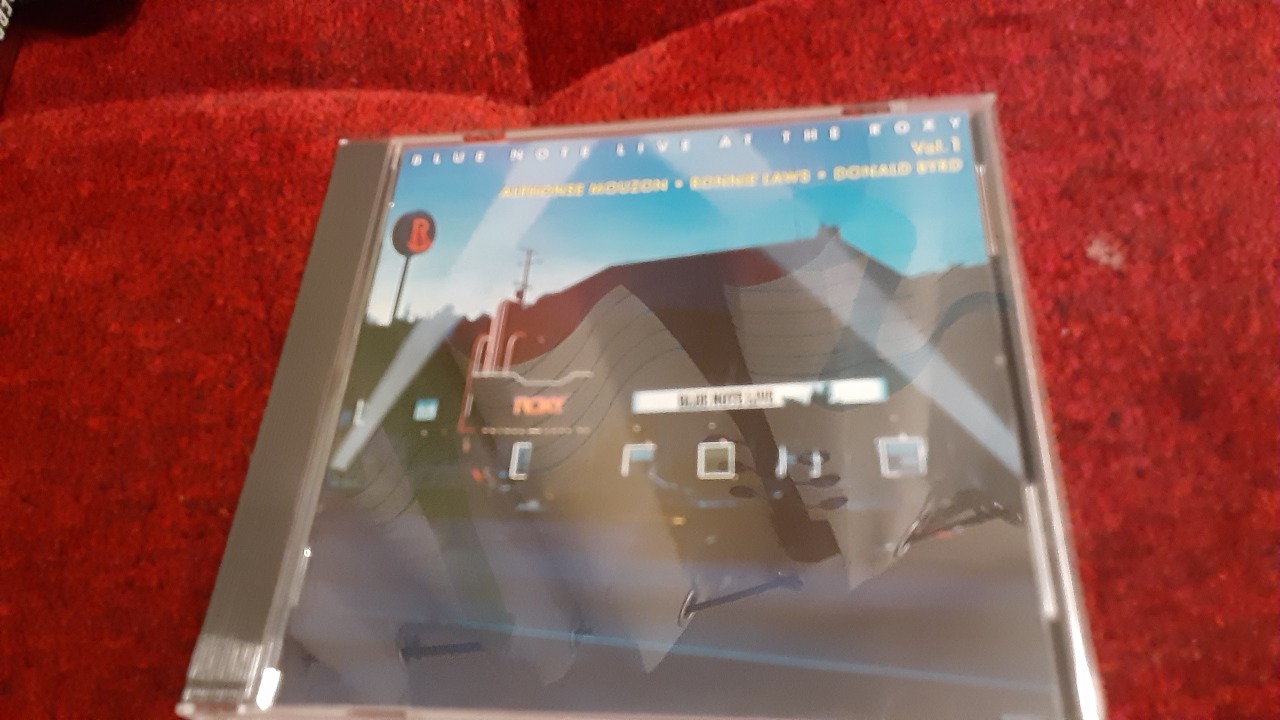

Shizuka’s Vault: A Funny Little Time Capsule of An Era: Blue Note Live At The Roxy (Blue Note, 1976)

(pictured: October 2021 Japanese CD reissues, from my collection)

Collective personnel include: Rosko: presenter; Alphonse Mouzon, Joey Baron, Steve Gutierrez, Ndugu Chancler, Keith Killgo, Gerry Brown: drums; Ronnie Laws: tenor saxophone; Robby Robinson, Bobby Lyle, Marshall Otwell, Kevin Toney, Gene Harris: keyboards; Earl Klugh, Bill Rogers: guitar; Donnie Beck; Ron Carter (bass overdubbed later), John Lee, bass; Donald Byrd: trumpet; and others.

Blue Note Live At The Roxy is one of those albums that upon its release in 1976, seems to have been just kind of “there”, and sort of sank from view with little memory of what it was. It’s a funny little time capsule of an era. Albums like this are lost to the dustbin of time, particularly in the streaming era. The release in many ways was seen as a microcosm in the Black American Music industry at the time as a product from a big corporate entity that swallowed the once influential and path breaking independent label, sort of using it as a brand, only in name (even redesigning the iconic logo). The album starts with a commercial, (yes, you heard right!) fading into the live audio from the Roxy nightclub in Hollywood. It seems to have a minor cult following amongst 70′s jazz and funk lovers, and that’s a reason besides being a part of my childhood I’m bringing attention to it.

To look at this album as product– It’s presence on vinyl is ubiquitous, regularly showing up on eBay, or Discogs, going as cheap as $2. It was released in four countries (according to Discogs) Even some sealed or near mint vinyl copies appear, a testament to how much of a machine this United Artists era of Blue Note was, that they were farming out copies of new releases in hopes an album would achieve the crossover success that the Larry and Fonce Mizell produced Donald Byrd and Bobbi Humphrey albums did, or the Larry Rosen and Dave Grusin (soon to strike a deal with Arista as a subsidiary for their GRP label, a leader in the digital recording and smooth jazz radio revolution a few short years later) produced Noel Pointer and Earl Klugh albums. Many of these, like Alphonse Mouzon’s The Man Incognito or John Lee and Gerry Brown’s Still Can’t Say Enough gained little traction outside R&B/funk circles, or gaining a small cult following in crate digging circles where recordings like these found new life in their sample laden breaks.

Blue Note was acquired by United Artists in 1971, after having been under the umbrella of Liberty Records since 1966. United Artists was under Transamerica Corporation which bought out the Liberty conglomerate. Blue Note remained an independent under founders Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff, when due to health issues Lion decided to sell the label in 1966, despite the success of Lee Morgan’s The Sidewinder (1963) and Horace Silver’s Song For My Father (1964) was in dire financial straits. Francis Wolff produced sessions often with pianist Duke Pearson overseeing A&R duties (sometimes serving as producer) and the sound of sessions like Hot Dog (1969) by Lou Donaldson, and the unreleased till 1980 Mothership, the wild, avant leaning final album for the label by organist Larry Young recorded in 1969, pretty much had the standard Blue Note sound Lion and Rudy Van Gelder created. When George Butler, who had worked at United Artists became Blue Note president in 1972, a marked shift

took place from a label with a strong legacy in artistry and innovation to a label that became something else entirely in the eyes of many, especially for purists, and fans of straight ahead jazz.

Why am I writing about such a marginal album in the first place and giving some historical background? It’s for people getting into this music, to be aware of the appearance of this much maligned era of Blue Note back into circulation (minus this album) on streaming, which very well because of the crate digging culture, may find a new audience beyond those who hit dance floors to these records in places like the UK and Japan . I also wish to mention this albums’ very brief and collectible nature on CD and the garish nature of this album, which I was introduced in my childhood makes it at least for me, memorable.

I was introduced to this album in my uncle’s vast record collection as an 8 year old. I was filing through records, saw it was a Blue Note, and saw it had the 70′s era UA logo I was crazy about which you see pictured at the top. Having grown up with Blue Note albums from the likes of Jimmy Smith and Kenny Burrell, as well as Donald Byrd, and because my mom and I also had Earl Klugh’s popular 1977 album Living Inside Your Love at home, plus my father having Donald Byrd’s Blackbyrd, I was familiar somewhat with this period of Blue Note. Blue Note Live At The Roxy also had Earl Klugh featured, as well as some other names I recognized like Ronnie Laws. Having been (and still am) a huge fan of CTI Summer Jazz At The Hollywood Bowl by the CTI All Stars, I thought this album might be similar. My uncle put it on his system and I think he played the Mouzon portion and I remember pretty heavy bass, which comes through on my Focal Chora 826 speakers loud and clear. The CD to me sounds just like the vinyl, which I had also played at my university radio station, apprenticing as a teenager long before I attended school there. Jazz record labels at this juncture in time in the 1970’s, started a trend of featuring their artists on package tours at major concert halls and clubs. While the practice of jazz in the concert hall was prominent in the 1930′s with John Hammond’s famous From Spirituals To Swing concert and through Norman Granz’ Jazz At The Philharmonic concerts starting in 1946. In the 70′s, producer Creed Taylor began the trend of record labels featuring their artists in concert to mainstream audiences starting with the CTI All Stars’ California Concert. Labels such as Arista, Pablo, ECM, Flying Dutchman, Columbia, Galaxy and Milestone followed the trend of these package tours and often times were released on double or triple album all star summits. Sometimes these albums would result in inspired, combustible playing, or just be absolute messes of awkward, incompatible musician styles. For an example of this label mega fest, there is none better than Columbia’s two infamous Montreux Summit (available on most streaming services) albums that included such incongruous style match ups as Dexter Gordon paired with Bob James, George Duke and Billy Cobham. Blue Note Live At The Roxy is a mix of both this kind of thing. Now that I’m no longer a purist and at the start of my forties, I can appreciate this album as fun and can say I enjoy it for what it is: a sort of overblown, over produced snap shot of Blue Note at the time, in the Butler era which I have often termed “the dark era of Blue Note”.

As Texas based saxophonist Jim Sangrey along with others in the industry who lived this moment in real time said on the Organissimo Jazz Forums upon Butler’s death in 2008:

The longer it went on, the more and more it was all about L.A. based studio dates, not about “slick street jazz” or whatever you want to call it.

As Sangrey elaborated in an earlier post perfectly summing up the United Artists Blue Note era

If you again look at the timeline, when Butler first assumed the lead at UA/BN, there were a lot of “pop-jazz” albums like Visions (Grant Green) by a lot of people. In retrospect, these were not as bad as they seemed at the time, although few were as good as you’d want them to be either. If he had stopped there, ok, the shift was on once UA/Transamerica, bought out Liberty (far more the turning point than Liberty buying out BN, I think), and it could have been just another case of corporate bullshit winning the day.

But he didn’t, and it wasn’t. The whole Blue Note Hits A New Note thing was enormous in terms of “push” (i.e. -marketing). You could sign up for a freakin’ newsletter for cryin’ out loud, in case you wanted to know how chapped Bobbi Humphrey’s lips were or weren’t at her last gig, I guess…This wasn’t intended to be just a co-opting of a label’s name, this was a hoped for movement, a redefining of a legacy/brand name/whatever. And almost all of it was crap and/or repetitious redoings of a formula that had worked one time. There was no “rebuilding” or “redefining”, just cheap opportunistic riding of a formula and farming out of work to slicksters, who did what slicksters do - make slick music for ready, and short-term, consumption. The only two “serious” artists left on the label were Hutch & Horace. The former’s output began to be produced (to lessening effect as time went by, imo) by Dale Oehler (Butler again being “Executive Producer”), the latter’s work shifting from Butler w/Marcus to Silver w/o any noticeable change, so I think this was one of those “stay out of the way” dynamics. And they got less and less push as time went by. Silver’s was the very last release of new, original material on BN before it went inactive, and believe me when I tell you that it was released damn near in a vacuum.

All “style” & no substance. Go to THIS PAGE and see how the covers got prettier and prettier while the music got emptier & emptier. And that’s not just a sign of the times either, since, as noted earlier, you can (and some did) make “commercial”, “jazzy” music that is not as totally devoid of content as most of this effluvia was.

I’ll give this much to Butler’s BN though - it laid the groundwork for GRP, since Dave Grusin & Rosen became an active production team there. So if you want some, any, kind of “lasting legacy” from it all, there it is, and you can have it.

Others, like the late writer, historian and radio host Chris Albertson pointed to how clueless Butler was in a lot of the choices made, and that several others in the industry had issues with him. Albertson remarked in the Butler thread, “he ran Blue Note into the ground” when the label ceased to release new music from 1978-1984. In 1985, Blue Note was jump started by a classic Town Hall NYC concert organized by then president Bruce Lundvall featuring returning label legends and new talent. In Butler’s defense it does take a certain kind of moxy to kind of push the label the direction he did to attempt to reach new audiences, despite it’s huge failure. It is the aforementioned L.A. session slick that dominates the Roxy album.

In 2012 it was reissued for the first time, anywhere in the world on CD in Japan as 2 separate CD volumes. This was a surprise to take such a minor, pretty obscure title and put it on CD with many others seeing the light of day from that era of Blue Note’s history. Given the nature of Japanese CD releases, at times being reissued again years later I took the plunge and bought both. I bought them to “represent the worst part of Blue Note” in my collection, often calling it “the worst Blue Note album ever made” but until I bought (from the same series) Blue Note Meets The LA Philharmonic (never reissued on CD since or available streaming as the original LP) I was pretty wrong. Natural Illusions (1972) by Bobby Hutcherson, and In A Special Way (1976) by Gene Harris are just putrid affairs that make you want to puncture your eardrums with a sharp device–examples of the effluvia Sangrey mentioned. The latter features Philip Bailey and Verdine White of Earth, Wind & Fire, but the arrangements by Jerry Peters (who produced Harris’ Tone Tantrum and played keys on many Mizell dates) are just empty, pedestrian, slickly produced for the sake of being produced. Harris sounds phoned in, and out of his natural element, the greasy, funky piano on Three Sounds albums or his much loved Concord albums from the 80’s to the 90’s.

Briefly returning to Blue Note Meets The LA Philharmonic, a kind of sequel to the Roxy album, the best portions are featuring Bobby Hutcherson and Carmen McRae, but the showcase for Earl Klugh, a monster player to be sure, with musaky renditions of his tunes “Cabo Frio” and “Angelina” from his debut Earl Klugh (1976) featuring full orchestra, were a reminder I never liked any other albums of his minus Living Inside Your Love. The aural wallpaper of these two tracks was a prime example of these over arcing productions and was nauseating. In January 2021, I lost these albums alongside 1,500 others in an apartment fire. Both Roxy albums nearly ten years after their initial reissue were reissued in October 2021, and I bought them again.

What Blue Note Live At The Roxy gets right in it’s four mini sets for marquee roster artists, is the presence of strong working bands. After the hilarious advertisement for the Blue Note Hits A New Note Campaign featuring the voice of radio personality (and former CBS Sports voice over artist) Rosko, the MC of the evening with a seriously funky backing track, the drummer Alphonse Mouzon takes the stage. The sadly departed Mouzon was the original drummer in Weather Report, was behind the kit on some of McCoy Tyner’s 70’s classics, who had also played with keyboardist Doug Carn, and around time of the Roxy concert was recording with Herbie Hancock. Mouzon’s first Blue Note Mind Transplant (1974) is an underrated jazz-rock classic, overshadowed by Billy Cobham’s Atlantic debut Spectrum the previous year. The album, which like Spectrum featured the late, future Deep Purple guitarist Tommy Bolin, asserted Mouzon was the next jazz-rock king on drums aside Tony Williams and Cobham. Mouzon’s group is playing selections from the newly released, absolutely awful The Man Incognito album but live, the three tunes are exciting showcases for Mouzon’s power and improvisational creativity during solos. “New York City” is actually pretty funny on The Man Incognito with a George Duke style monologue, on Roxy it’s simmered down to a bit of gritty street funk with whanging guitars. “Without A Reason” has a lengthy solo intro, on a hi fi system, Mouzon’s drums are truly in your face, and keyboardist Robby Robinson worships at the space pod of Chick Corea and the styling of Jan Hammer with screaming mini Moog. The danceable groove with guitar solo is broken up by a drum/percussion duet with Mouzon and percussionist Rudy Regalado.

Ronnie Laws is next with his band Pressure, playing music off his Wayne Henderson (of Crusaders fame) produced Pressure Sensitive (1975) and recently released Fever (1976) with it’s hilarious cover of Laws covered in steam. The band is locked in tight, with tasty keyboards from Bobby Lyle who’d be a star in smooth jazz just a few years later. Laws, who contributed some pretty free interludes on Earth Wind & Fire’s Last Days In Time (Columbia, 1972) contributes some searing playing not really heard on his studio albums save “From Ronnie, With Love” on Fever during the Blaxploitation/adult film funk of “Captain Midnight”, then slowly dials things down on the now standard in smooth jazz circles, “Night Breeze” composed by Bobby Lyle. Lyle’s Rhodes solo is effervescent and effective. The CD shuffles the LP order a bit by featuring the double album finale of Donald Byrd taped on location on July 19, 1976, at Central Park next playing his hits “Places and Spaces” and “(Fallin’ Like) Dominoes with the Blackbyrds. There is obviously post production here with an overdubbed announcement from Rosko and applause taken from the Roxy concert and faded in. This is the end of CD 1, when on the LP it represented the final two tunes on side 4. The band does a great job of capturing the essence of the Mizell’s intricate arrangements. Is Byrd’s playing in peak form here? No… in my opinion his peak playing can be found on albums like Byrd In Hand (1959), Free Form (1961), A New Perspective (1963), but by this time Byrd had devoted much of his time to being a professor at Howard University, and teaching, and he had earned six graduate degrees starting three groundbreaking jazz studies programs. The trumpet chops don’t matter when it’s about the grooves here.

Carmen McRae represents a high point on the album to be sure, the audience is really INTO it, and her rendition of “Ain’t Nobody’s Bizness If I Do” is really whimsical. It’s also interesting to note Joey Baron who has been one of the most creative drummers in free improvisation and the Downtown New York scene is the drummer in her group. It was one of his first gigs as a young musician, and he mentioned in a recent Downbeat interview he had to play Mouzon’s drums and stand up just to attack the cymbals! Not a setting one would imagine him in, but really he laid a solid backing for her. What really represents the album as a time piece of the era is the ridiculous 5 or so minutes of a proclamation given to then label head George Butler, on behalf of then mayor Tom Bradley, except Councilman Dave Cunningham was representing Bradley. The speech by the Carolinian Butler is excruciating, sounding as if he has a German accent, and was this concert that huge that this bit needed to be included for posterity? It’s absolutely absurd and hilarious and probably has some weird sample possibilities. Butler did bring Woody Shaw to Columbia, but axed him when they wanted to push Wynton Marsalis, and he apparently played a role in Miles Davis’ final post retirement Columbia albums before his switch to Warner Brothers. The Earl Klugh medley shows just how good a player he was, especially in stripped down settings and the “Blue Note ‘76” track is a bit odd for the fact that it’s really a pseudo jam session with the evening’s principal artists with the addition of some of the cream of the crop of LA session players (including one saxophonist Fred Jackson The same that recorded a one off for Blue Note in the 60’s and recorded with John Patton?) It can be enjoyed as long as the listener doesn’t expect much, it’s kind of a generic funk number that was a dime a dozen for the time, Earl Klugh lays down his best Benson isms here. It’s also odd that the only Bobby Hutcherson appearance is this track (on marimba). Again it’s a fun listen but not earth shattering.

I just think that for whatever reason it’s strange the album especially in it’s first CD reissue from 2012 is more expensive than it should be. Each volume on CD for $12-15 is reasonable, but more than that? No. The album for me is a memory of childhood and a fun listen because of how 70’s cocaine and drugs kitsch it is, with some spots of some really good playing. The production value is high and does sound quite nice on a good hi fi, but this article is not my customary review so absent are my review ratings. Barring if you have the few key Donald Byrd or Bobbi Humphrey Mizell produced titles of this era, honestly is all you need. Blue Note Live At The Roxy is a perfect snapshot of what this era of Blue Note was. Thanks for reading about this obscure, funny time capsule of an era.

Note: For record label and variant obsessives, it seems that Japanese pressings featured the white “b” logo variant, which is seen on the CD. Also, Thanks to Jim Sangrey. His perspectives are truly one of a kind, and offer utterly singular unique views of what it was like hearing something of the era in real time.