It must be good to be a judge.

You make your own calendar, preside over high-profile cases where you have expressed an opinion about the outcome, delay cases to please the benefactor who appointed you and lash out at his prosecutor, making his life miserable—at least until the appellate court rebukes you.

Don’t worry if this raises eyebrows in Congress. You can dismiss suggestions of impropriety, arguing that the judiciary is independent, even if the Constitution grants judges no independence when it comes to non-judicial activities. And your ranting push-back will be fully ventilated in The Wall Street Journal, where you can be interviewed by an attorney who will be appearing before you in a landmark tax case.

If you become a super judge, you can take an extraordinary expense-paid vacation aboard a super yacht. You can party to your heart’s content with litigants before the court. Getting there is half the fun, and you will find a private plane at your disposal. Don’t even ask who is footing the bill. He may have business before the court. You don’t want to know.

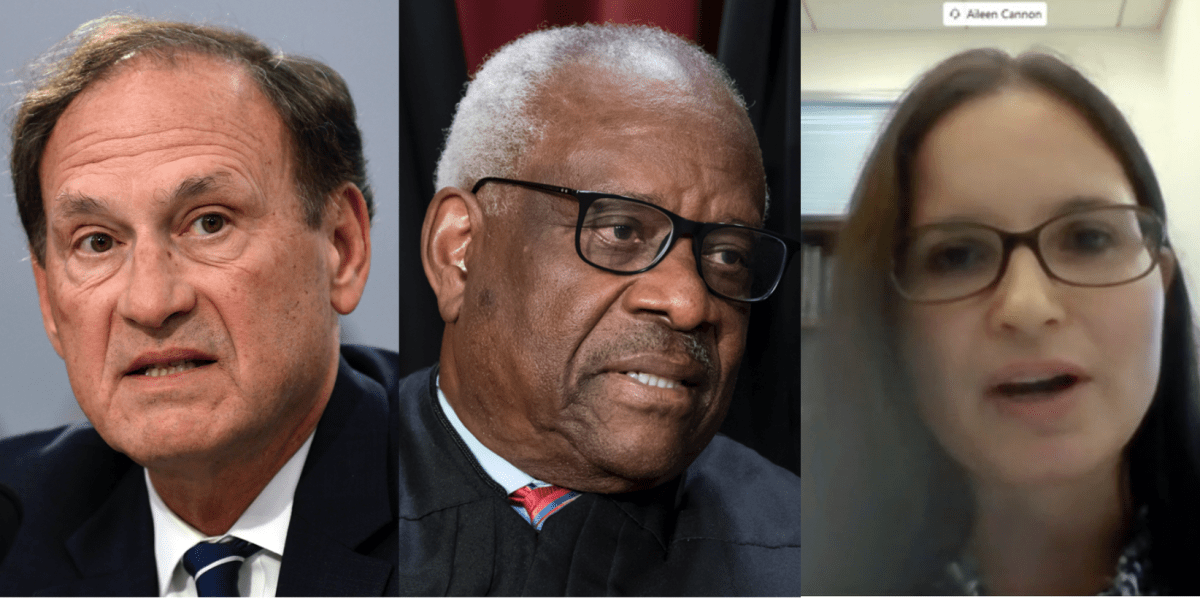

Summer may be over, but the super judge fun isn’t. Samuel Alito is not only defending his lavish-all-expense-paid trip to Alaska. He’s defending it to a journalist-lawyer who has business before the court. If you’re Aileen Cannon, the federal judge in Florida overseeing the Mar-a-Lago documents case, go ahead and insult the special counsel bringing a landmark prosecution to your courtroom.

The stunning displays of judicial arrogance from the likes of Alito and his colleague in having rich people pay for your vacations boggle the mind. Clarence Thomas, as well as lower court judges like Cannon, didn’t emerge out of nowhere. The judiciary has always had its share of the ethically challenged. But they seem more empowered now because we have a Supreme Court that is often described as conservative but is hardly cautious, restrained, respectful of the tried and true. It’s a court that easily chucks decades of precedent and engages in intellectual sleights of hand that are less subtle than a three-card monte player.

For instance, you can say you are a textualist and an originalist when it suits your ideological interest to straitjacket an 18th-century document in a way that ignores 21st-century values and technological change. In interpreting a document, a preamble is always an important way to inform the judge of the meaning of what follows, except when it comes to the Second Amendment (Clarence Thomas calls it the “forgotten amendment”), where we can ignore the reference to “a well-regulated militia,” and decide that everyone has a personal right to carry a handgun or an AK-47, which “shall not be infringed.” We hold the very words of a statute sacred until we don’t. That’s why the Supreme Court ignored the very words in the laws at issue in key environmental and student loan statutes and substituted its own “major cases doctrine,” a bit of sophistry that allows the court to say, “Surely, Congress didn’t mean that.”

Judges are the keepers of our sacred right to justice. To be sure, lawyers will, as Gilbert and Sullivan put it, always try to “hoodwink a judge who is not over wise.” But most judges will wield their awesome power judiciously despite attempts to bamboozle them.

Consider the issue of federal removal jurisdiction—whether one can have one’s case moved from state to federal court. This is the go-to-move for defendants in Trumpland as they try to have their trials moved out of state court in Georgia for seeking to overturn the state’s support for Joe Biden in the 2020 presidential election.

The minuet over removal was cut short in New York State, where Donald Trump was indicted for falsifying business records to cover up his hush money payoff to Stormy Daniels. He awaits trial in the state, not the federal court.

Trump, hoping for a better jury pool than the one found on the island of Manhattan, where he was a resident in happier times, sought to remove the case to the federal court under Section 1442(a) (1) of 28 U.S.C. which allows “officers … of the United States” to remove a civil or criminal case brought against them in a state court, if the case is “for or relating to any act [performed by or for them] under color of [their] office.”

The court and the parties assumed that Trump, as a former officer of the United States, could be removed if he satisfied the requirement that the payoff involved a presidential act. As the court put it: “It would make little sense if this were not the rule, for the very purpose of the Removal Statute is to allow federal courts to adjudicate challenges to acts done under color of federal authority.”

Where, when, and how federal officials can be held legally accountable for things they did in office (or at other times) is a moving target. In 1982, the Supreme Court held 5-4 in Nixon v. Fitzgerald that the disgraced former president may not be sued for damages arising out of acts within the “outer perimeter” of his official responsibility while in the White House. Ernest Fitzgerald was a Pentagon contractor who lost his job after testifying about malfeasance in the Defense Department. Nixon was no longer president at the time of the suit. The court held the immunity attached to him anyway, although the Court made clear that there were times when a president could be sued. Years later, the Court held that Paula Jones was free to sue then-President Clinton over sexual harassment from when he was the governor of Arkansas, arguing, naively, that it would not unduly burden his presidency. (The Jones suit led to the impeachment and all that followed.)

In the Trump payoff case in New York, Federal Judge Alvin Hellerstein, after a hearing, denied removal on the basis that concealing a payoff to a porn star was not remotely what we pay presidents to do.

In the Georgia prosecution of Mark Meadows, Trump’s White House Chief of Staff and former congressman sought removal to federal court with the insistence that his alleged interference with the federal election was part of his official duties. There, the parties also assumed, as did the judge, that Meadows, as a former federal officer, could invoke the criminal removal statute if his case otherwise qualified for removal.

Denying removal after a hearing, Steve Jones, a federal judge, found no federal jurisdiction because, while some of the overt acts in furtherance of the alleged conspiracy fell within the ambit of Meadows’ job (getting on a phone call with the president), the charged conduct (conspiracy to overturn an election) itself did not. Meadows immediately ran to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals for relief.

The Eleventh Circuit, in considering a fast-track briefing schedule, leisurely asked to see the wine list. We should not be surprised; that’s what judges do. They ordered the parties to brief an issue never raised by anyone in any court, namely whether Meadows, as a former federal officer, had standing under the statute to remove the case. If there is no standing, former officers like Trump and Meadows don’t even get out of the gate on removal. That’s all she wrote. Case closed.

The court order said:

“In certain circumstances, 28 U.S.C. § 1442(a)(1) permits ‘any officer (or any person acting under that officer) of the United States or of any agency thereof, in an official or individual capacity,’ to remove a civil action or criminal prosecution from state court to federal court. Does that statute permit former federal officers to remove state actions to federal court or does it permit only current federal officers to remove? Compare 28 U.S.C. § 1442(a)(1), with 28 U.S.C. § 1442(b) (permitting removal of ‘[a] personal action commenced in any State court by an alien against any citizen of a State who is, or at the time the alleged action accrued was, a civil officer of the United States and is a nonresident of such State . . .’).” (italics mine).

Lawyers like to believe they are members of a learned profession. So they talk in Latin. When I went to law school, I learned about two tools of construction, in pari materia and expressio unius est exclusio alterius.

For those of you not conversant in Latin these days (after all, it is a dead language), the first canon is to interpret properly the meaning of a statute. The judge may read it with a statute in a neighboring zip code. Here, the neighbors couldn’t be closer. They are subparagraphs of the same code section and should be read together.

The second principle is that the expression of one thing is the exclusion of the other. Thus, Congress expressly made §1442 (b) to include present or former officers when it came to removing a civil action but omitted to include former officers when it came to removing a criminal action. Was this sloppy draftsmanship or a legislative design to exclude former officers from the coverage of the criminal but not the civil removal statute?

Trump will also seek removal in Georgia. So will other defendants caught in the dragnet launched by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis. But in the end, the criminal cases of all 19 defendants will probably reside where they were begun—in the Georgia state court. The quest for removal will never get out of the starting block, which is as it should be. Even in an age of slipshod ethics and jurists like Alito, who sounds like James Cagney in White Heat taunting the police to come and get him, the law is sometimes so plain, and judges have enough modesty, that arrogance loses, at least for a decent day in court.