It could drive a person crazy. Everyone is wondering what the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will do with the Colorado decision disqualifying Donald Trump from the state’s ballot. The state’s highest court ruled that under Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, he must be banned the same way ex-Confederate States of America officials could not run for Congress or president following the Civil War. Other states could follow.

Many assume SCOTUS will reverse because the conservative supermajority is supremely partisan. Professor Orin Kerr of the University of California, Berkeley School of Law thinks they will “decide the case based on their best understanding of the law,” but that may prove naive.

It’s true that the Supreme Court does not like to make political decisions that might overtly influence the outcome of elections. It didn’t back Trump’s seditious arguments from 2020. Perhaps it learned a lesson from Bush v Gore, the 2000 five-to-four decision where the tilting vote came from the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who later said she regretted what she had done.

Remember, though, three justices–John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett–are Bush v Gore alumni who worked as lawyers to achieve George W. Bush’s election by legal fiat. What’s sauce for the goose ought to be sauce for the gander, but they, too, might now regret the decision. The only remaining member of the Court from Bush v Gore is Clarence Thomas, who may, but probably won’t, recuse himself since he appears to be in bed with the Trumpists. That might make four justices who think the Court ought to resolve election disputes, especially where the election is for the presidency.

The justices realize they lose legitimacy if seen as supremely partisan, ignoring precedents and stretching the meaning of constitutional provisions to achieve preferred policy goals but they seem not to care. Gallup reports their approval rating among concerned citizens is 41 percent, near the record low because the public thinks they are politicians in black robes.

The Court’s conservative majority says it adheres to the doctrinal trail of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who was a textualist (What are the words used by the framers?) and an originalist (What was society’s original understanding then as to what those words mean?). Ironically, if they decide to reverse Colorado, the originalists will not be following their doctrine. The very originalism and textualism that Scalia was so proud of leads inexorably to Trump’s disqualification.

Scalia used to trash the Court’s liberals and the professoriate whose approach to constitutional interpretations, he asserted, was: “The Constitution means what I would like it to mean.” The Constitution is “dead, dead, dead,” he told a group at Princeton in 2012. It means what the society at the time understood the words to mean. Of course, he preferred originalism in interpreting the Constitution in 1789 to the words of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, which guaranteed freedom and equality to all citizens.

The liberals on the Court may believe that the outcome opens the floodgates to a parade of horribles.

The individual justices are replete with their own biases on disqualification. Thomas loves Trump. Before the Court decided to enact its toothless code of ethics, he accepted a lot of good stuff from Trump supporters, like private plane trips, a home renovation, a junket on a super yacht, and private school tuition for a grandnephew he was raising. His wife, Ginni Thomas, thinks Trump won the 2020 election and called Joe Biden’s victory a “heist.” Alito, who only got an Alaskan fishing trip from conservative benefactors, still hates anything that might give the edge to the Democrats.

Trump tapped Neil Gorsuch for the Court, as well as Kavanaugh, and Barrett, and they may feel they owe him big time. Roberts is a closet conservative who talks about institutional reputation and public legitimacy as he signs on to wrecking-ball partisan opinions.

They all will say that disqualification takes the decision from the voters. But so do a lot of provisions in the Constitution. A 16-year-old can’t run for president even if the country craves a teenage “stable genius.” Nor can Arnold Schwarzenegger (he might be good, but not a natural-born citizen). Nor can Barack Obama (I miss him, but he’s termed out). Going back to the Civil War era when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, Jefferson Davis could not.

In our federal system, judges and cabinet members, for example, are nominated and confirmed but not elected, as they are in many states. The Constitution takes their appointment away from the ballot box. Of course, that’s what the Constitution is all about. It is the “supreme law of the land,” vigilant in its protection of the minority from the tyranny of the majority.

But there must be a way out for conservative justices who might want to see Trump back in the White House, appointing more kindred jurists, investigating his political enemies, nullifying those pesky indictments against him, and cheering their ruling in Dobbs.

SCOTUS will be hard-pressed to hold that Trump did not engage in an insurrection. “Doing so,” says legal pundit Roger Parloff, “would enshrine their disingenuousness in the US Reports forever.” He adds the observation that Trump refused to testify in Colorado. He did in New York. Neither the trial judge nor the Colorado Supreme Court drew the time-honored inference that a defendant’s failure to testify in a civil trial gives rise to an inference that his testimony would be unfavorable.

Still, Parloff’s bottom line is that SCOTUS will reverse the Supreme Court in Colorado because it is a terrible policy. The voters should decide, the line goes, and it is bad policy to take political decisions away from the voters. Ironically, Trump’s disqualification stems from his attempt to take the political decision from the voters. It is he who was anti-democratic, not Colorado’s supreme court.

So, Parloff thinks that the Nine will be looking for an “escape hatch.” Sarah Wallace, the trial judge in Colorado who ruled that Trump should remain on the ballot, lacked the nerve to disqualify the 45th president even though she found that he “engaged in an insurrection” on January 6. She concluded that Trump was not an “officer of the United States,” nor did he take an “oath to support the Constitution” within the meaning of Section Three. The entire Supreme Court of Colorado overruled these conclusions. Even the dissenters weren’t going to buy either of these arguments. Trump himself referred to himself in the New York Stormy Daniels case as a “former officer of the United States,” and the oath he took to “preserve, protect and defend” is an oath to support unless he took it with fingers and toes crossed.

So Parloff sees the only credible escape hatch is in a matter known as In re Griffin, the only case where a Supreme Court justice squarely took on the meaning of Section Three. Griffin was an 1869 case where the Supreme Court’s Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, sitting as a circuit judge, refused to vacate a criminal conviction because the trial judge had fought for the Confederacy. Griffin’s Case is hardly a super-precedent that should be respected, unlike the super precedent Roe v. Wade, which they trashed anyway.

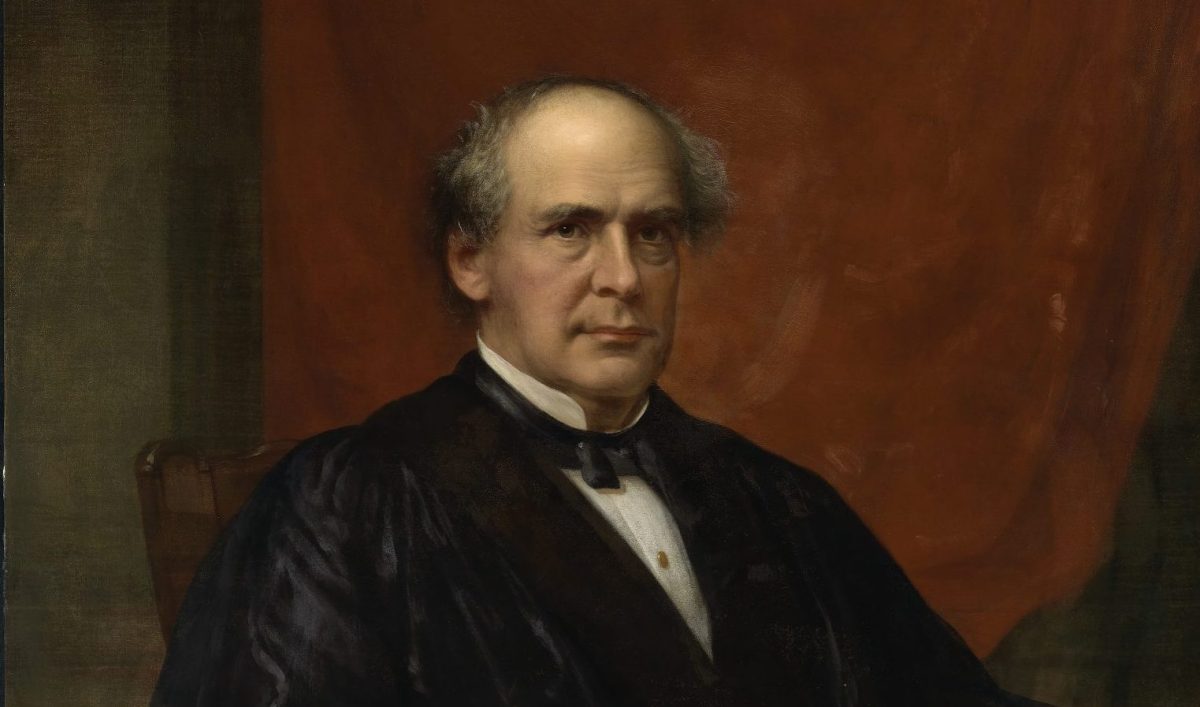

You might remember Salmon P. Chase. He was an Ohio senator and governor who was Abraham Lincoln’s secretary of the treasury before the Great Emancipator nominated him to be Chief Justice of the United States–an opponent of slavery replacing the despised Roger Taney of Dred Scott infamy. Chase’s picture was on the ten thousand dollar bill before it was withdrawn from circulation. (Washington Monthly Legal Editor Garrett Epps describes Chase’s ruling and the worst reasons to restore Trump to the Colorado ballot.)

In Griffin’s Case, Chase held that Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment is inoperative unless and until Congress passes enabling legislation. In their seminal law review article last April, legal scholars, notably conservative law professors William Baude and Michael Stokes Paulsen, concluded that Chase was just dead wrong. “his reasoning that the Fourteenth Amendment is not self-executing is unsustainable.”

The facts in Griffin’s Case are these. Caesar Griffin, a black man, was sentenced to prison for shooting someone with intent to kill. He was tried and convicted in a Virginia state court. He sought to vacate his conviction, neither on the basis that the trial was unfairly conducted nor that he was the victim of racial discrimination. Griffin’s point was that the trial judge, Hugh W. Sheffey, whose fairness Griffin never challenged, had done previous service as a member of Virginia’s secessionist legislature. Chase found that Sheffey “was one of the persons to whom the prohibition to hold office pronounced by the amendment applied.” There is no argument there.

Griffin mounted a petition for habeas corpus in federal district court seeking to vacate his conviction on the ground that Sheffey was disqualified under Section Three. The district judge granted the petition, and Chase, sitting in the court of appeals, reversed it. Chase noted that the remedy sought, vacating Griffin’s conviction, worked mischief because it did not seek the removal of Sheffey from office, which was the “main purpose of the amendment.” So Chase made up a new rule of constitutional construction, the doctrine of convenience. The doctrine, he conceded, “cannot prevail over plain words and clear reason.” But, a construction that occasions “public and private mischief” must not be preferred to a “construction which will occasion neither.”

Chief Justice Marshall had said in United States v. Fisher: “Where great inconvenience will result from a particular construction, that construction is to be avoided, unless the meaning of the legislature be plain; in which case it must be obeyed.”

Chase, in Griffin’s case, was all over the place. Realizing the weakness of his argument that Section Three is not self-executing, he staked his decision on the alternate ground that Sheffey, even if disqualified, was acting under the color of office. Therefore, Griffin’s conviction must be upheld. The core of Chase’s opinion is that there would be catastrophic consequences in that it might invalidate official decisions throughout the South and elsewhere. But, if Sheffey was acting “under color of office,” and the conviction stood, there would be no inconvenience and no disastrous consequences in making Section Three self-executing.

Griffin was wrongly decided because Chase’s reasoning was wrong. There is no ambiguity in Section Three. Its meaning is: You are disqualified from office if you breach your oath to support the Constitution. Full stop. Chase’s reasoning was pure and simple which Scalia treated with howls of execration: “construe the constitution to mean what you would like it to mean.” As Baude and Paulsen put it: “Bluntly, Chase made up law that was not there in order to change law that was there but that he did not like.” They added: “[T]his is not how judging is supposed to work, even if it too often does.” The Colorado Supreme Court gave Griffin short shrift.

Chase’s opinion in Griffin’s Case is untrustworthy. In the treason prosecution of Jefferson Davis, Chase, again sitting as a circuit judge, held two years earlier that Section Three barred the treason prosecution, in part, because Section Three “executes itself” and “needs no legislation on the part of Congress to give it effect.” As Emerson famously said: “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Also, Chase sought the nomination of both the Dixie-dominated Democratic Party and the Republican party of Lincoln and U.S. Grant.

So, the only seeming escape hatch for SCOTUS to overrule the Colorado Supreme Court and restore Trump to the ballot is pretty underwhelming.

The Constitution requires the disqualification of Donald Trump. Will the Supreme Court do it or at least, allow the states to do it? Applicable is the trenchant statement of Justice Robert Jackson: “We are not final because we are infallible, but we are infallible only because we are final.”