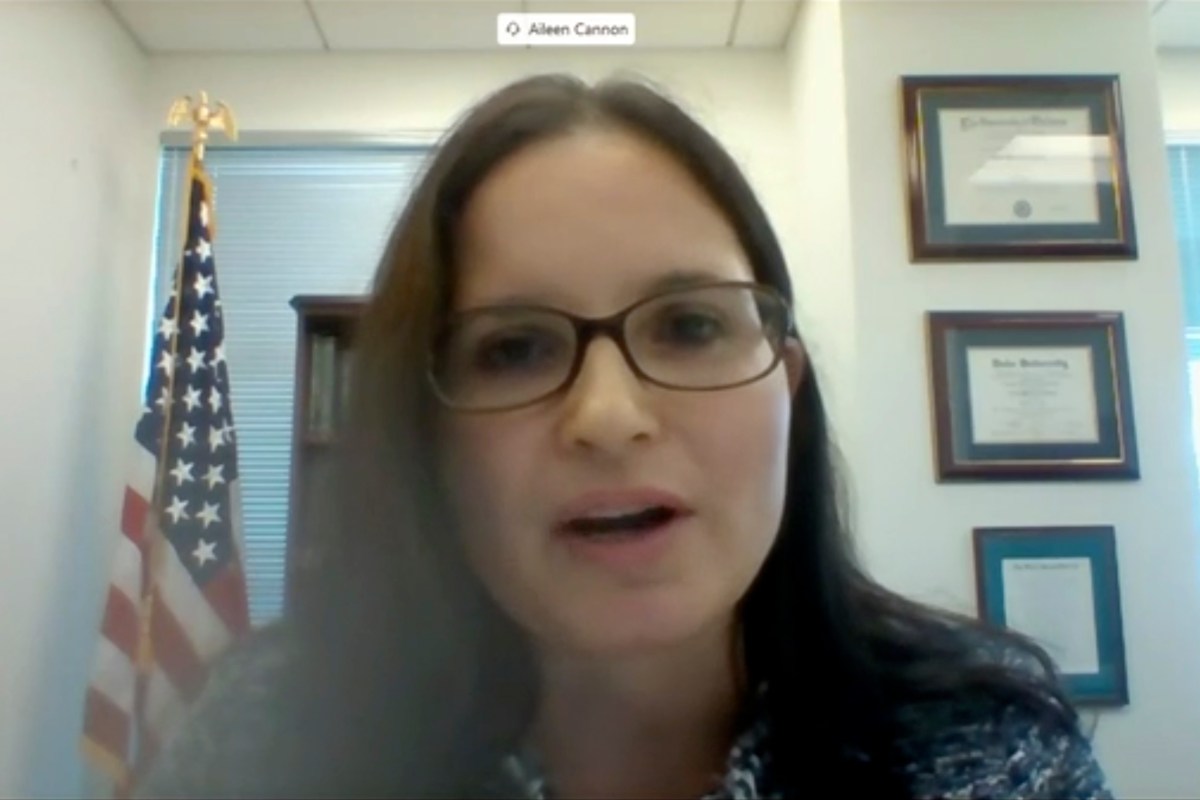

The 37-count indictment of Donald Trump presents the inexperienced Judge Aileen Cannon with several challenging legal issues involving trial management.

Trump stands charged before a court that demands justice for the defendant, to be sure, and justice for the United States of America.

Special Counsel Jack Smith is committed to a speedy trial, so there is a jury verdict before the election. The public is entitled to this, but don’t get your hopes up, even though Cannon is asking for motions from both sides to be submitted by July 24 and has set a trial date of August 14. These dates, of course, can and will be extended. Trump may argue that putting him on trial while he runs for office is judicial meddling in the political process. And it will likely take more time to resolve the myriad motions Trump will file than Cannon is now allowing.

The Mar-a-Lago documents case is, of course, one of many Trump faces. In New York, there is the criminal case arising from his payoff to porn star Stormy Daniels, the now amended second E. Jean Carroll defamation case, seeking additional damages for his additional disparagements of her character. The alleged defamation arises from his being found liable for sexual assault in a department store dressing room. There is also the civil action for damages for business fraud brought by New York’s Attorney General Letitia James. On the horizon is the Fulton County, Georgia, prosecution of election interference and the January 6 case, almost certainly to be filed by Smith in the District of Columbia, for insurrection and seditious conspiracy.

One of the motions Cannon must adjudicate involves how to treat over 197 classified documents. Under federal law, the court must balance the government’s interest in national security and the defendant’s due process right to be confronted with the evidence against him. This requires obtaining security clearances for the lawyers, possibly the fact witnesses, and experts who might be called. Arrangements for this are already underway. Trump’s lawyers will argue that they are entitled to discover and inspect all 197 classified documents the government seized at Mar-a-Lago, not just the 37 mentioned in the indictment. A seasoned judge could dispose of these issues in days or weeks; how long it will take Cannon is another question.

Trump is likely to argue that he’s a victim of prosecutorial misconduct as he did in his interview with Fox News’s Bret Baier on June 19. This is scurrilous but familiar. Trump and his late father made similar allegations in a housing discrimination case that the feds brought against them in 1973. In the Florida case, Trump has claimed prosecutorial misconduct, alleging that a Justice Department attorney offered to help a lawyer for a witness get a judicial appointment in return for cooperation. Of course, the prosecution denies this, but the allegations may require a time-consuming hearing.

The Sixth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees the accused in a criminal prosecution the “Assistance of Counsel for his defense,” which means the accused can communicate with their lawyer under a privilege from discovery.

The privilege, however, is not unqualified. The communication is privileged if the client confesses a past criminal act to the lawyer. But, if the client tells the lawyer they plan to commit a criminal act, the communication falls within the so-called crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege. The lawyer may be compelled to testify what the client told him. On their face, Trump’s statements to his lawyer, M. Evan Corcoran, state an intention to obstruct justice by keeping documents from the grand jury.

Most of the 37 counts the grand jury returned against Trump in Florida involve Trump’s willfully retaining classified documents. Still, as noted by Trump’s own Attorney General William P. Barr, himself no paragon of the politically independent prosecution, “[at] its core, this is an obstruction case.” As Barr puts it: “Trump personally engaged in an outrageous course of conduct to obstruct the grand jury inquiry.” Although the damning communications between Trump and his attorney are relevant to Trump’s state of mind on all counts, only two specifically involve the communications between Trump and Corcoran, who presumably will be a witness at the trial.

Typical of such conversations is one cherry-picked by venerated columnist Thomas Friedman writing in The New York Times, who quotes the following from the indictment, which has Trump saying to Corcoran:

“I don’t want anybody looking through my boxes, I really don’t. … What happens if we just don’t respond at all or don’t play ball with them? Wouldn’t it be better if we just told them we don’t have anything here?”

Corcoran, perhaps to protect himself, took contemporaneous notes of his conversations with Trump and then dictated his notes into his iPhone. It is unknown whether the notes were headed with the typical label “Privileged and Confidential,” as most lawyers would be careful to do.

We do know that Chief Judge Beryl Howell of the federal district court in D.C. ruled last March that Trump’s communications with Corcoran fell within the crime-fraud exception and were discoverable by the grand jury investigating the matter.

Cannon can revisit this issue before or during the trial if Corcoran takes the stand. An intelligent assessment of where this issue should go cannot be made without seeing the entire memorandum or hearing from Corcoran. A client consults a lawyer to mold his conduct in compliance with the requirements of the law. Often, the client will suggest courses of action that are inadvisable or even illegal. It is up to the attorney to try to talk him out of it or else resign. Corcoran hasn’t left (yet), but at least 12 Trump attorneys have resigned in the past three years.

That Corcoran took contemporaneous notes may raise eyebrows among most savvy criminal lawyers, whose practice is to be wary of painting a target on their client’s back.

Trump’s seasoned trial counsel, Todd Blanche, will doubtless make a pre-trial motion to suppress all Trump communications with Corcoran. The question is whether Cannon will entertain the motion before or during the trial. A trial judge more experienced than Cannon might well consider the motion during the trial to avoid unnecessary delay. This was the approach I saw as a federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York, where the trial judges were the best in the country. But, with Cannon, who knows—particularly since she appears to harbor a favorable attitude toward Trump based on her presiding over the search warrant aspect of the Mar-a-Lago documents case?

Should she wish to revisit the privilege issue, Cannon may hold a hearing. Whether this occurs before or during the trial will be up to her. Cannon has tremendous and unreviewable discretion in trial management. But, even if Cannon rules out Corcoran’s testimony about his communications with Trump, he would presumably be allowed to testify about what Trump told him about the storage room location of responsive documents. This will gauge Trump’s deceitful conduct in directing, without his lawyer’s knowledge, that many relevant boxes be removed from the storage room, thus preventing a complete search. This deception caused his attorneys to falsely certify to the government that a “complete” search had been conducted.

I haven’t given up on Cannon. She has been a Trump loyalist, but that was before the 11th Circuit twice reversed her summarily in the search warrant case. Concerned with her career as a judge, she may have gotten religion. Her aspirational, even if unlikely, August trial date indicates as much.

James D. Zirin is a former federal prosecutor in the Southern District of New York.