Two massive X-class solar flares released over the past few days have caused radio blackouts across the Pacific Ocean.

The first flare, on August 5, was measured as being an X1.6-class solar flare, and was released from sunspot AR3386, which also resulted in a coronal mass ejection being flung out into space. The second, released on August 7, was an X1.5-class flare.

The flares hit the Earth and caused shortwave radio blackouts, with mariners and ham radio operators around the Pacific experiencing signal loss at frequencies below 30 MHz.

Solar flares are bursts of X-ray radiation from the sun's surface, usually from areas of high magnetic activity, like sunspots. The greater the amount of magnetic energy that has built up and been released, the more powerful the flare will be.

"Solar flares are ranked into five lettered categories in terms of strength (A, B, C, M and X) of which X-class flares are the strongest," Rami Qahwaji, a visual computing professor and space weather researcher at the University of Bradford in the U.K., told Newsweek.

"Within each letter class there is a finer scale from 1 to 9. Each letter represents a 10-fold increase in energy output. So an X-class flare is 10 times more powerful that an M-class flare and 100 times more powerful than a C-class one.

These solar flares were classified as X1.6 and X1.5, putting them at the lower end of the X-class flares in terms of power. These flares usually occur approximately 10 times per year.

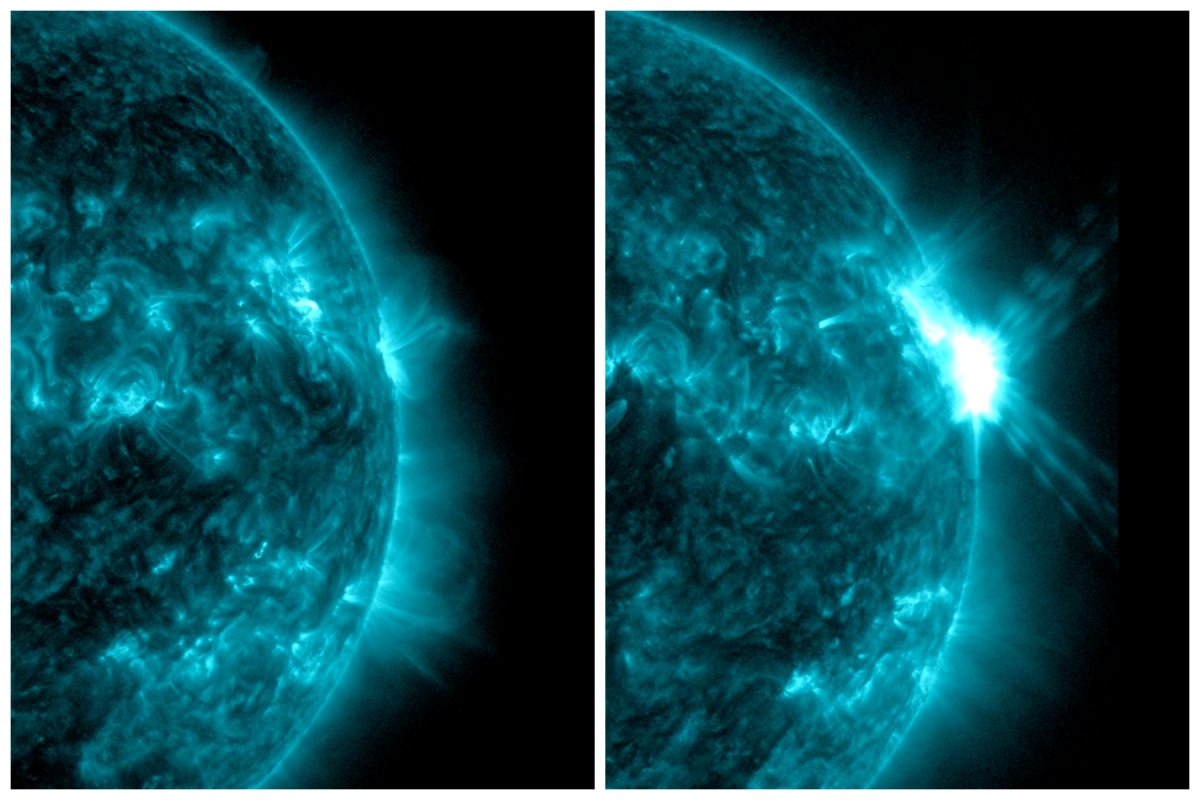

The Sun emitted a strong solar flare on Aug. 5, peaking at 6:21 p.m. ET. NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory captured an image of the event, which was classified as X1.6: https://t.co/4fyBJuUfVW pic.twitter.com/DJKyiE29wy

— NASA Sun & Space (@NASASun) August 7, 2023

Solar flares cause radio blackouts due to their effect on the Earth's atmosphere and magnetic field. Usually, high-frequency radio waves rely on the ionosphere to bounce signals from the sender to the receiver. The X-rays of a flare ionize the atmosphere, which results in the radio waves being degraded or even completely absorbed.

"When an M-class or X-class flare occurs, ionization could be produced in the lower and more dense layers of the ionosphere (the D-layer)," Qahwaji said.

"This ionization can cause radio waves that interact with electrons to lose energy due to the more frequent collisions that occur in the higher density environment of the D-layer. This could lead to HF [high-frequency] radio signals [becoming] degraded or completely absorbed, resulting in the absence of HF communication, primarily impacting the 3 to 30 MHz band (radio blackout)."

Civil aviation is the primary industry that can be affected by radio blackouts like this, as aircraft often rely on long-range communications over large remote areas or oceans with no ground-based radio networks in between.

"Many aircraft also have satcom as backup, but high-frequency is mandatory as part of international agreed procedures," Mike Hapgood, a space weather scientist at the STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the U.K., previously told Newsweek.

"So high-frequency blackouts can disrupt those links, but in general only for a few tens of minutes, so the industry can work around that disruption. These blackouts will not affect take-off and landing as aircraft will then use short-range VHF radio links."

Solar flares are often accompanied by a coronal mass ejection, or CME, which is a plume of solar plasma flung out from the sun. This X1.6 flare was followed by a CME, but it is expected to only hit the Earth in a glancing blow on August 8 or 9, possibly combining with another previous CME to form a "cannibal" CME. The X1.5 flare was also followed by a CME, but that one is expected to miss the Earth entirely.

A cannibal CME is when a smaller CME is overtaken and engulfed by a larger, faster-moving one, consuming and combining the two plumes of solar plasma and radiation.

Correction on the month under timing in this graphic. The flare peaked as an R3 event on 7 Aug at 4:46pm EDT. The flare was long duration and officially ended at 5:18pm EDT, but remained above R1 levels until 6:44pm EDT on 7 Aug. pic.twitter.com/4WG0OMsMiu

— NOAA Space Weather (@NWSSWPC) August 8, 2023

The majority of solar flares are mostly harmless, with the exception of radio transmission disruption. More powerful flares may have much more serious impacts on the Earth, however.

The most powerful X-flare in recorded history is thought to have occurred in 2003, measuring in at a whopping X28.

"However, it is believed that the most significant solar storm event happened in 1859 and is generally referred to as 'The Carrington Event.' Back then we didn't have critical digital infrastructure, similar to what we have today. But an event similar to the Carrington Event happening today could result in between $0.6 and $2.6 trillion in damages to the U.S. alone, according to NASA spaceflight," Qahwaji said.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about sunspots and solar flares? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.