Dr Josh Wright

President, British Society for Haematology

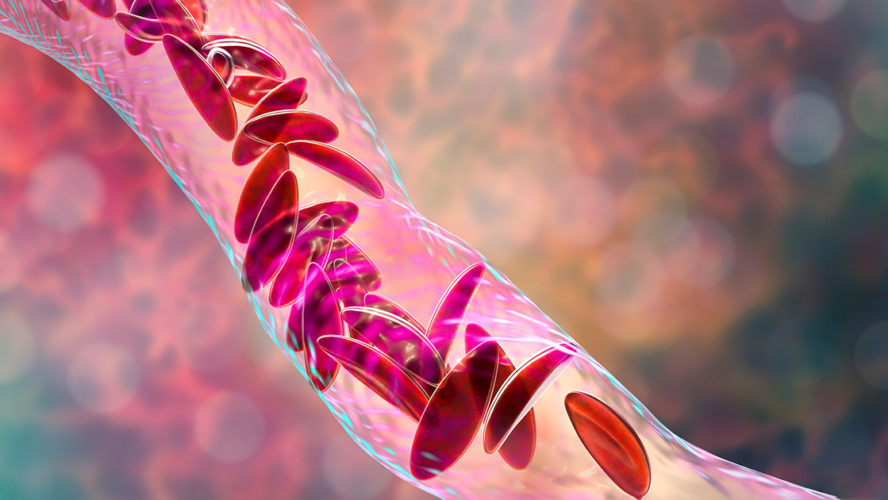

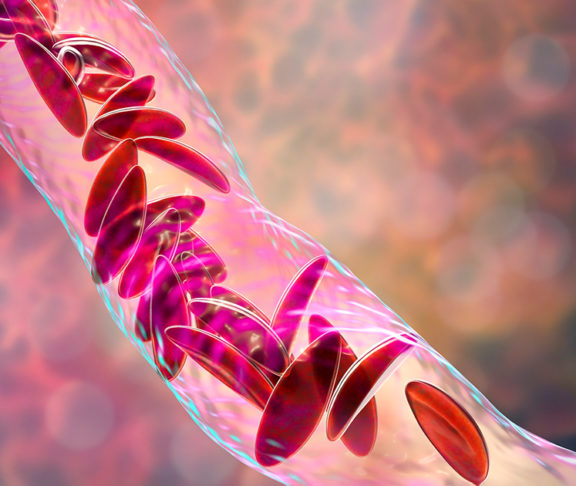

Sickle cell disorder mainly affects people from African and Caribbean backgrounds. It’s an inherited blood condition that can shorten life and lead to severe unpredictable bone pain which blights many individuals’ lives.

How would you feel if from a young age, you knew what you were likely to die from? If you had witnessed friends or relatives die young from the same illness? If your life and routine were frequently punctuated by episodes of severe pain? Angry? Frightened? Depressed? Desperate? Probably a combination of all of these. How about if the services the NHS offered you were patchily distributed, under-resourced and in some cases, frankly inadequate?

Sadly, this is the case for many patients in the UK with sickle cell disease.

A disease affecting any bodily system

Very strong painkillers can be required when someone is suffering what’s known as a sickle cell crisis. In addition to the pain, sickle cell disease can affect almost every organ in the body, from strokes in childhood to kidney, lung and liver failure in later life.

It is the most common inherited blood disorder – more prevalent than cystic fibrosis. Around 15,000 people have it in the UK. But the funding for sickle cell, which mainly affect Black people, is dwarfed by the amount spent on other inherited diseases affecting Caucasian populations.

Sickle cell disease can affect almost every organ in the body, from strokes in childhood to kidney, lung and liver failure in later life.

Addressing variations in care

Although there are dedicated teams of doctors, nurses and psychologists delivering good care to those with sickle cell disease, services for this group of patients are still underfunded and neglected.

So, what can be done? Most importantly, greater investment is needed in services for patients, in education about the condition for NHS clinicians and in research into new and better treatments. Some patients get good NHS treatment, but for others, it can be poor. We have to overcome that variation.

All 42 Integrated Care Systems (ICS) around the country should commission sickle cell services so that there is a uniformly high standard of care delivered everywhere. Hospital trusts need appropriate facilities where specialists can look after patients and have enough funding to employ those specialist doctors, nurses and other staff to do so.

Potential treatment options

There is an increasing range of potential treatments for sickle cell disease; new drugs with the potential to ameliorate the disease; stem cell transplants; and further down the line, hopefully, gene therapies with a potential to cure this dreadful disease. There are lots of other ways the NHS can do better for sickle cell patients. For example, making it free for all of them to get prescriptions.