Research rewards

Capstone projects prove beneficial to PharmD students

The School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences’ research emphasis appealed to Nicole Ink, PharmD ’22, before she ever set foot on campus.

But being a pharmacy student took on added appeal when she learned at orientation about the school’s graduation requirement: a capstone research project.

“I’ve always loved science and have been a curious person,” Ink says. “The thought of doing research was exciting. The capstone project and its research track jumped out to me. I said to myself: ‘I want to try that.’”

Ink did more than “try.” Her project was honored at the school’s 2022 capstone poster presentation, and she is now putting her research skills to use in a clinical-pharmacy residency at Guthrie Robert Packer Hospital in Sayre, Pa.

The Candor (N.Y.) High School graduate is just one of the PharmD students who has conducted pharmacy-related research with faculty and preceptor mentors.

“This is beneficial to students because it broadens their CVs, broadens their opportunities and opens their eyes about what other career paths pharmacists can take,” says Mohammad Ali, assistant professor of pharmaceutical sciences and director of the capstone program. “Pharmacists can be involved in clinical research, scientific research and even in post-doctoral fellowships with industry. The capstone program gives them a head start in those directions.”

The enterprise and expectations

Including a capstone project in the curriculum was a priority for the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences when it opened in 2017, says Tracy Brooks, associate professor and vice chair of pharmaceutical sciences.

“From the get-go, the focus here has been a research-intensive pharmacy school,” says Brooks, who works with students on capstone projects. “How do we make students appreciate the value of research? How do we involve them and expose them to some degree so they can understand the research enterprise and its values and difficulties, even if their career goals don’t include research again?”

The capstone program, which Brooks says is offered only at 25%-30% of pharmacy schools nationwide, provides PharmD students the opportunity to work in a solo research track or as part of a group setting.

“I start with them early in their second (P2) year with a series of seminars that introduces them to the capstone idea, the timeline and the expectations,” Ali says.

About five to eight students per year choose the solo track, while the remaining 60-70 take part in group research, Ali and Brooks say. For the group projects, Ali asks faculty members and preceptors to submit project applications, which are then examined and chosen by a capstone committee at the school. In a capstone project open house, the students meet with faculty members and preceptors to ask questions about projects. The research groups (usually containing four students) are then given a week to rank projects in their order of preference.

“We do our best to give them one of their top three [choices],” says Ali, who adds that there are 16-17 accepted projects per year.

In the solo research track (which has GPA requirements), students are involved in the project idea and work with faculty members or preceptors to propose their project to the capstone committee. Those students then take a three-credit lab in their third year to prepare for and initiate the research.

“It’s like a mini-thesis,” says Brooks, who coordinates the solo tracks. “In general, the research track students want more depth in their projects.”

But the group projects also offer challenges, she says, particularly for the faculty member or preceptor making the pitch.

“It has to be something that is of interest, but not an imminent requirement,” Brooks says. “They have to come up with a proposal, but wait about a year and a half before students are actually with them to do it.”

All students work on projects during their final year and make a poster presentation in the weeks before graduation.

From intimidation to excitement

By the time students present their capstone posters, they are feeling assured and have gained a great deal of research knowledge. For many, it’s a far cry from the initial capstone discussions as P2 students.

Ink says she felt unsure about herself before embarking on a project with Ali examining DNA damage repairs in cancer cells.

“I gained a lot of confidence,” she says of the experience. “I started at Binghamton hesitant and afraid to make a mistake. As I went on, it was exciting to see this novel idea [grow]. I stopped worrying and focused more on what was happening with the project.”

Joseph D’Antonio, a 2023 Doctor of Pharmacy candidate from Hauppauge, N.Y., admits to being nervous when he first learned about the capstone requirement while interviewing at the pharmacy school in early 2019.

“To the uninitiated it can seem like a large and daunting task,” he says. “In our third year, we got to choose our research project and I have been beyond excited ever since. … When you read the school information resources and see ‘capstone — requirement’ listed in the fourth year, it automatically makes it feel intimidating. This feeling was exceptionally misplaced, but caused me to waste quite a bit of time being anxious about it looming on the horizon throughout my pharmacy-school career.”

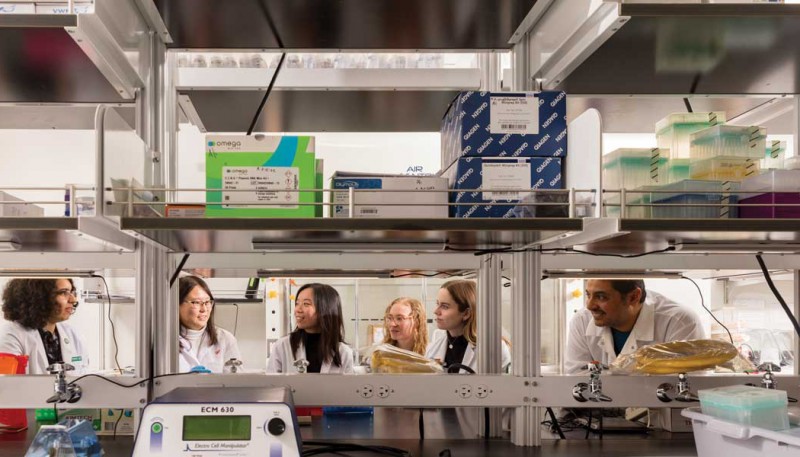

D’Antonio is now working with fellow PharmD candidates Juhi Gurtata, Mana Halaji Dezfuli and Eric Kelly on a project mentored by Tony Davis, assistant professor of pharmaceutical sciences, on drug molecules that might inhibit a key protein that plays a role in the tuberculosis proteasome pathway.

Gurtata says she was “indifferent” about the capstone requirement until examining the research projects proposed by the pharmacy school’s faculty.

“I got to learn more about the professors and their areas of interest, along with learning what interests me to potentially do research in,” says Gurtata, who adds that the capstone project has been one of her best experiences as a pharmacy student.

Results and conclusions

During the capstone process, students often discover that science does not always work as planned, Brooks says. And that’s OK.

“We see failures all the time,” she says. “It’s a normal thing. You have to revise on the fly. In science, you can come up with a great idea and it doesn’t go the exact way you planned. So you’ve got to go with the flow.”

It’s a lesson that D’Antonio and his group have already learned.

“Research is not straightforward,” he says. “There can be a massive difference between theoretical and practical pharmaceutical science, and in order to succeed in the research field it requires that you maintain a certain level of broad vision. This comes in handy when results of a given experiment end up not being in line with your hypothesis. It allows you the ability to step away from the protocol and question why things turned out how they did. From there you can go back and make small tweaks and adjustments to confirm your initial results and make improvements.

“Our particular research is important because tuberculosis is still one of the leading causes of infectious disease deaths in the world,” D’Antonio says. “Exploring the repurposing of existing therapeutics to perhaps treat this grave disease could perhaps one day save millions of lives.”

For Ink, conducting research in the capstone program led to her interest in oncology. The Guthrie residency has “scratched the itch” for still being involved in research, she says.

“I love working with patients and I love research,” she says. “One thing that made me go to residency is that we also [conduct] research there. It’s clinically based, but it’s also correcting data and determining results. It’s solving a puzzle that can lead to benefits for patient outcomes.”

The capstone program helps students such as Ink because it is a “differentiation,” Brooks says, as the research experience will make their pharmacy education and background stand out.

“It’s also going to help them appreciate science: new ideas, new drugs, the evaluation of one drug over another,” she says. “They can appreciate what comes behind all of those new discoveries, recommendations and guidelines. Even if students never do research, they can at least appreciate its value in the clinical field.”