The room Jenny Quinn shares with her 10-year-old son is about 10 sq metres, kitted out with the most basic furniture and dominated by what looks like a prison-issue metal bunkbed on which they both sleep. There is a small en suite bathroom; behind a heavy wooden shutter, the window looks out on to a bare expanse of concrete.

“He’s in drama therapy in school, for anxiety,” she tells me. “He cries a lot. He doesn’t believe in Santy [Father Christmas] any more. He’s not an angry child, but he’s lonely: he’s so, so lonely. There’s no kids his age here: they’re all babies. The PlayStation’s his best friend, because he can get on that headset and talk to his friends from school. That’s it.”

For want of a flat with a secure tenancy, the two of them have lived here for almost two years, in what the Irish government calls a “hub”: a residential centre for homeless families, of a kind introduced in 2017. This one is run by a housing association called Respond, and is the temporary home of about 35 adults – most of them single women – and their children.

With hideous symbolism, its location was once the convent adjacent to the biggest of the Magdalene laundries: the prison-like workhouses run by nuns in which thousands of unmarried mothers were incarcerated and serially abused. This one was called High Park. In 1993, a mass grave was discovered here, which was found to contain the remains of 155 women. Quinn says the place has a sense of “negativity in the walls”; she does her best to shield her son from any conversations about the facility’s awful past.

The night before I meet Quinn, I stay in a flat just to the north of Dublin’s city centre, booked via Airbnb, which she and her son would presumably jump at. As if to prove that I am not the only person there paying for a short let, there is a gaggle of young men in the flat above me, who – despite the fact that it is Monday – repeatedly sing a dire and apparently drunken version of Robbie Williams’s Angels between midnight and 1am. But the buggies and tricycles on each landing suggest that most of my temporary neighbours are families.

I pay £95 for a single night’s stay (including a £43 “cleaning fee”), which highlights why whoever owns it has decided to rent it out in this way. The same move has been made by scores of other landlords: in August 2018, there were reckoned to be 3,165 entire properties listed on Airbnb in Dublin, compared with only 1,329 available for long-term rent.

This is one vivid element of a housing crisis that combines the most contorted aspects of the private market with a rising need that continues to go unanswered. About 10,000 people in Ireland are reckoned to be homeless. The number of families who have nowhere to live has increased by more than 20% since 2017. These are national problems, but they are inevitably concentrated in Ireland’s capital, home to more than 10% of the country’s population. In the four months between June and September, 415 Dublin families – including 893 children – became newly homeless, adding to a total across the city of about 1,400. Increasing numbers are being forced to live in hotels.

Meanwhile, residential neighbourhoods echo to the clack-clack-clack of suitcase wheels. The city is smattered with key boxes for Airbnb apartments. A stock line among activists demanding action from the government gets to the heart of all this: in 21st-century Dublin, they say, homeless families stay in hotels, and tourists stay in houses.

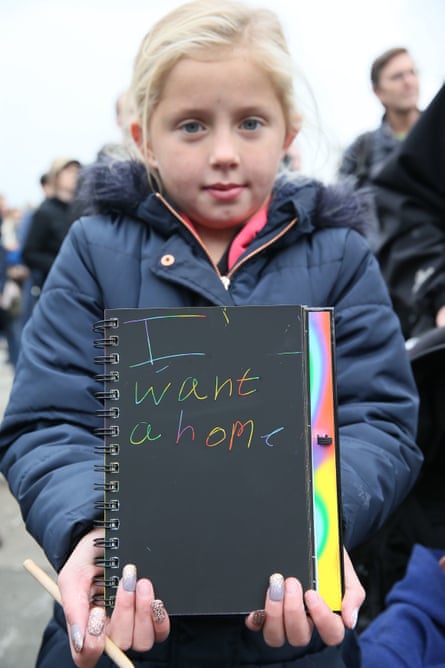

Last week, a survey titled the Expat City Ranking found that among people who live and work abroad, Dublin came out as the world’s worst capital for affordable accommodation. Since the summer, there have been repeated protests in the city, focused most spectacularly on occupations of vacant buildings. This Saturday, a protest organised by the National Homeless and Housing Coalition is expected to attract thousands of people to the middle of Dublin, set on making the case for housing as a basic human right and venting their anger and fear about a simple enough fact: that Ireland’s capital is fast becoming an impossible place to live and thousands of lives are being ruined as a result.

Quinn’s story is a perfect case in point. Until February 2017, she and her son had been living in a two-bedroom flat in the Dublin suburb of Finglas. She had spent a long time working as a PA before her father’s diagnosis with cancer triggered a spell of depression that left her unemployed. To make things even more difficult, her landlord then decided to sell up, which forced her to suddenly confront a private-rented housing market in which the monthly rent for anything similar was well over €1,500 (£1,300). In the absence of any available social housing, she had no option but to declare herself homeless.

The most she has been offered so far is a government-assisted move back into a private-rented flat funded by a new benefit called housing assistance payment. She says that in the current housing climate, a private tenancy would put her at risk of the same experience she had last year (“I could take it and then a year later that landlord could decide to sell and I’ll be back at square one”), and more disruption for her son. So, she is currently on a waiting list for a council flat that could take years to materialise and in the middle of a predicament that extends to her friends and relatives.

“I have two friends who both work full-time,” she says. “They came home from New Zealand three years ago. They’re living in their ma’s shed. Their two kids are in bunkbeds in the house. I have friends in their 30s who can’t leave home. I have friends who live in log cabins.”

Within minutes of arriving in Dublin, the urgency of Ireland’s housing crisis is highlighted by how often the issue crops up on the TV and radio. The Greater Dublin area is reckoned to have more than 30,000 properties that are completely empty, many of which are owned by the local council. Thanks chiefly to Ireland’s corporate tax rate of 12.5%, Dublin is home to the European HQs of Facebook, TripAdvisor, LinkedIn, Twitter, Google, eBay and, poetically enough, Airbnb. The number of high-paid employees who work for such companies is one of the reasons advertised rents in the city now average around €1,900 a month. As Brexit grinds on, there are fears that if companies relocate from the UK to Ireland, it will only add to Dublin’s housing problems.

For all that the crisis has specifically Irish elements, it is full of echoes of what is happening elsewhere. In the UK, at least 320,000 people are homeless, about 170,000 of them in London. In Copenhagen, youth homelessness has increased by 75% since 2009. Between 2013 and 2017, the number of homeless people in Warsaw rose by 37%. In Athens, one in 70 people are reckoned to have nowhere to live. Even in Germany, the supposed embodiment of “social Europe”, there is rising anxiety about a homelessness problem made much worse by the fact that state-owned homes have been sold in huge volumes to private investors. In most of these cases, you find much the same basic themes: the decline of public housing, the arrival of gentrification, the way that tourism now collides with the housing needs of local people, and the sense that city economies built around multinational companies inevitably exclude thousands of people.

The first person I arrange to meet in Dublin is Rory Hearne, an academic who is at the heart of the swirl of politics and protest around the housing crisis. When we talk in the cafe of an upmarket hotel near Dublin’s main railway station, he traces what is happening in Ireland back to the 1980s and the way that successive governments restricted the building of public housing. “In the 1970s,” he tells me, “a third of all new housing was built by the state. But by 2006, it was down to 5%.”

The free-market boom that saw Ireland’s economy hailed as the Celtic Tiger, he goes on, was partly built on the easy availability of mortgages and a frenzy of house-building and land-buying, both of which fed into the crash of 2008. In its wake, Ireland saw the phenomenon of “ghost estates”: housing developments left unfinished as funding suddenly dried up. At the same time, mortgages and property portfolios were sold at knock-down prices to international “vulture funds”, which also bought up huge swathes of land that often have been left empty – partly, says Hearne, because scarce land and housing keeps rents and property prices high.

In 2014, Ireland began a supposed economic recovery, recently crowned by an annual economic growth rate of over 5%. “But you had a private construction industry that had been decimated,” says Hearne. “You also had a generation coming in who can’t get mortgages, and the growth of precarious work. And all these things come together: people who either used to get housing from local authorities, or who bought their home, were now all going into the private rental sector. So, of course, what happened? Rents started shooting through the roof.

“Homelessness also started to rise. You now see this completely new phenomenon called family homelessness: predominantly lone parents, because lone parents’ welfare was cut. Rents are rising, benefits are being cut – and they’re being pushed into homelessness.”

Since then, he says, the housing shortage has reached parts of the population who would once have considered themselves relatively affluent. “I had a class last week: a mixture of mature and regular students. I asked them: who thinks they’ll own their home? Out of 80, not one person put up their hand. That’s a shocking, shocking thing.”

Dublin’s ongoing wave of housing protests is partly the work of people who were energised by the successful campaign to repeal Ireland’s ban on abortion. They burst forth again this summer, in the form of a new umbrella group called Take Back the City. In August, its activists occupied a building called Summerhill House, which had until recently been the temporary home of foreign students, said to be paying €450 a month to stay four or five to a room, in bunkbeds. The protests then moved to another empty building on North Frederick Street, where a 12-day occupation was eventually ended by a mixture of private security guards and police officers. To the shock of observers, some of the security guards and the police wore masks.

Protesters then occupied a third building before, in October, about 30 activists moved on to Airbnb’s offices in Dublin’s old docklands district.

Conor Reddy is a 23-year-old genetics undergraduate at Trinity College Dublin, and a key Take Back the City activist. We meet just after he has finished his morning’s lectures; among the first thing he mentions is that he still lives at home with his parents. “If you live in Dublin, that’s very common; almost universal,” he says. “So, I guess I can’t complain. But I’ve got one friend who lives in Gorey in County Wexford and, throughout the first and second year in college, he was commuting every single day. Four hours a day in a car or a bus. People are commuting crazy distances. They can’t engage with college life; they have no time.”

Reddy talks me through what Take Back the City has been doing since the summer, and his own involvement in the protests. At North Frederick Street, he says, his exit from the building was followed by police violence: “We kind of wanted to have a blockade of the road. And within a moment, I was grabbed by five or six officers and dragged behind their riot van, out of sight of everybody … and I got knees, and elbows, and punched. There were three of us who were hospitalised. And it was interesting that the people who were arrested were people who had been very vocal in the media.”

A police spokeswoman commented that the body’s role at such events “is to facilitate peaceful protest while protecting the rights of individuals to do their lawful work safely … Our objective with any such operation is to ensure the safety of the public.”

Later the same day, I spend an hour and a half with a Take Back the City insider who will only go by his first name, Aaron. As well as talking, we visit two of the city-centre properties occupied by protesters: huge, opulent Georgian constructions that are still mystifyingly empty. In one of them, there are signs of what recently happened: most notably, a poster pressed up against a dusty window that simply says: “This could be a home.”

“I’m a 32-year-old man, still living in my parents’ house,” Aaron tells me. “As far as my friends and people I know are concerned, half of them don’t live in Ireland any more. They live in Australia or Canada. Why? Lack of jobs after the financial crisis and, when the economy improved, no houses to come back to here.”

He explains the techniques of what he calls “political occupation”, whereby a day is divided into four shifts, and no one can stay in an occupied building for more than two shifts in a row. “You don’t want people to get burned out,” he says. “You’re constantly in fear that the door’s going to get smashed in.” He talks me through the temporary occupation of Airbnb’s offices, which were being used as the location for a series of public talks as part of a day of events focused on Dublin’s architecture, and thus suddenly open to a protest.

“The actions have to be symbolic in some way,” he says. “While we’ve been heavily involved in demanding the use of public land for housing, Airbnb is compounding the crisis even more. We’re in the midst of a housing emergency, and Airbnb plays a large role in that. And as much as we focus on public land and public housing, Airbnb has to be brought to account as well.”

If Ireland’s housing crisis has a face and voice, it is probably Erica Fleming, a 33-year-old mother of one who is now a student at Trinity, studying for a degree in English. In 2015, she was working as a receptionist at a Dublin company when she went through a relationship break-up and found that her €1,000-a-month earnings meant she had no hope of finding a flat. “I asked Dublin city council for help,” she says. “The only option was to present me and my daughter as homeless.”

Over an hour in a crowded Caffè Nero, she explains her experiences and how much they have changed her. She and her daughter became homeless before the hubs were introduced, so she had no choice but to find a hotel or B&B that would accept her, and then re-contact the council, which would foot the bill. “But at the start, nowhere would take us,” she says. She spent months pinballing between places: “We had a night here, a night there, with a carful of stuff. I was still going to work every day, with Emily going to school.”

Eventually, she found a hotel that allowed them to stay for just under two years. “Emily used to always say: ‘How much longer, how much longer, how much longer?’ That was a constant question. And then one day, it dawned on me that she hadn’t asked me. And it just killed me. Because I knew then that she had given up.

“I was trying to keep it together so well that I had become robotic. You’re just in the one room, so you don’t want to let your child see any hurt or pain that you’re experiencing. You want to be the person that provides stability. So I used to put Emily into bed at night-time, turn off the lights, and I’d go and sit on the toilet and cry.”

During this time, she would regularly contact the city council about the empty houses she saw. “I was showing them photos and saying: ‘Here’s a property, here’s a property, here’s a property.’ We were passing these houses every day. Council houses. And because I’d gone public, people – carpenters, plasterers, painters – were getting in touch with me, saying: ‘We will do it up for you. Just get the key.’

“But the council wouldn’t do it. They said that for safety reasons, they couldn’t agree. That really did my brain in. It made no sense at all.”

Like Quinn, Fleming resisted the suggestion that she should use the housing assistance payment system and move into a private-rented flat, for fear of being evicted. In April last year, she moved into a council flat, whose rent is assessed according to her income. Her decision to become a student via Trinity’s access scheme, she says, was motivated by the fact that without more qualifications: “I was never going to get ahead, ever. There was just a constant poverty trap.”

In between her studies, Fleming is now a regular speaker at housing protests, and a familiar presence in the Irish media, where she has gone through a grimly predictable process of being variously praised, doubted and intruded on. Like just about everyone in Ireland’s new housing movement, she has seemingly simple demands: action on the issue of empty properties, and a huge new programme of public housing. She is both baffled and outraged by what she sees as the government’s reluctance to act.

“It’s pure lack of will,” she says. “Nobody can sit here and justify why there are so many boarded-up properties. I cannot explain to you how much that irritates me.”

Ireland is governed by the centre-right party Fine Gael. So far, its proposed solutions have extended to a plan to assist in the building of 150,000 new homes over the next 20 years on plots the government owns, 40% of which will be classified as either “social” or “affordable”. What exactly these terms mean remains unclear: in an emailed statement, a spokesperson for the Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government said that “there is no legal definition of an ‘affordable home’ – the cost reduction will be decided on a site-by-site basis”. Even if the homes concerned are genuinely within people’s reach, Hearne insists that the drawbacks of the policy are self-evident. “The majority of the housing that’s going to be built will be unaffordable,” he says. “What sort of housing policy is that? What sort of economic policy is that? Where is any sort of logic in it?”

Central Dublin – along with 20 other areas of the country – is now classified as a “rent pressure zone”, which caps annual rent increases at 4%, but politicians and activists claim this gets nowhere near tackling the causes of skyrocketing housing costs. In the capital as a whole, rents still went up by an average of more than 12% in the year to March 2018.

Independently of its 20-year goals, the government has plans for social housing that were first implemented in 2016 under the banner of “Rebuilding Ireland”. It claims that this will result in the creation of 50,000 such homes by 2021, two-thirds of which will be newly built. Hearne cautions that official numbers of “new” social homes include existing properties that have simply been refurbished, and that the vast majority of the demand for social homes will continue to be met by pushing people into private-rented housing and making payments to their landlords, a policy that critics say simply adds to rent inflation. As they see it, all this boils down to a depressingly familiar problem: the Irish establishment’s bedazzlement with the very same free market that caused the country’s housing crisis in the first place.

There are two other elements of the Irish government’s plans. It now has what it calls a “national vacant housing strategy”, which, among other things, means that councils have been requested to draw up “vacant homes action plans” to set targets for the number of empty homes that “can ultimately be brought back into use, whether for private sale or rent, or for social housing purposes”. And, in an attempt to tackle the problems sown by Airbnb and its ilk from June next year, an annual cap of 90 days will apply for the short-term renting of properties.

The Dublin charity Inner City Helping Homeless (ICHH) carries out unending outreach work with the city’s rough sleepers and also does its best to help families who simply cannot find anywhere to stay. Among the people who keep it going is Brian McLoughlin. Until last year, he worked at the Dublin offices of eBay; he now does “a bit of consultancy work” between unpaid work at the charity’s city centre HQ. “I feel a little bit like I’m using my brain for good rather than evil,” he says.

As he sees it, the government’s plan to restrict Airbnb rentals to 90 days will not tackle the fundamental problem in central Dublin. “A landlord could still rent somewhere on weekends through the year,” he says. “They could make enough money from that not to go through the worry of getting a permanent tenant.” He believes the cap should be 40 or 50 days. He and his colleagues, he says, have heard from people evicted by landlords who claimed they needed to refurbish or redevelop their flats, only to see their former homes advertised on Airbnb, “with no refurbishment done. Nothing.”

It is perhaps some token of the mess that sits underneath the housing crisis that McLoughlin’s charity has tried to talk to Airbnb about what is going on, to no avail. “We’ve reached out to them on more than one occasion. You don’t get anything back. We wanted to sit down and have a talk, but we didn’t get a reply.” My repeated attempts to get Airbnb to contribute a comment to this article drew a similar blank.

The company’s role in the housing crisis is not just a matter of flats booked online by tourists; in a particularly surreal twist, ICHH increasingly uses Airbnb to find emergency accommodation for homeless families. “That’s a regular thing,” says McLoughlin. “In the first six months of this year, I think we spent €30,000 on families coming to us late at night, when homeless services had told them to go and sleep in a police station. They come here with their children at half eight, half nine at night, and we have to jump on with an Airbnb or a short-term let, and pay the money just to get that family somewhere for a night.”

Not for the first time, I get the strong impression that one of the key things standing in the way of any resolution of Ireland’s housing crisis is that the status quo aligns with an array of powerful interests. Landlords benefit from endlessly rising rents; hoteliers receive millions of euros to put up homeless families. McLoughlin puts the problem in simple terms: “Homelessness is a massive business for a lot of people, so why would they want it to end?”

At one end of the crisis, then, lies no end of money. At the other are thousands of people who are barely clinging on. Quinn says the reason she wants to talk about her homelessness goes back into her family history. “It’s the mental health aspect,” she says, explaining that four of her immediate family were once at a so-called “industrial school” called Goldenbridge, run by nuns. “Every one of them became alcoholics,” she says.

She then turns her attention to homelessness, and life in hubs like hers. “I think you are now going to have a generation of young girls that are addicted to anti-anxiety medication and antidepressants. I can’t get through a day without taking my anti-anxiety medication. If I was to stay here with you without taking it … well, once I get going, I’m fine. But once I’m in that room, I feel like I can’t breathe. I feel like the walls are closing in on me.”

In the Airbnb where I stayed, the next occupants are presumably living the short-let dream of pristine furniture and fittings, Deliveroo food, plentiful booze and Robbie Williams singalongs. Meanwhile, in their room at the hub, Quinn and her son are grimly killing time.

She is not allowed any alcohol in her room, nor any visitors. “There are even simpler things we’re not allowed to have, like a candle,” she tells me. “On a Friday night when my son goes out with his dad … I don’t have money to go out any more.

“But to be able to light a candle, and have a bottle of wine, stick on a bit of Netflix – Jesus Christ, is that too much? Is that not just normality?”