Experts agree ventilation is crucial to lessen the risk that Covid-19 spreads as students go back to school. However, proper ventilation is more an aspiration than a reality in some Vermont schools even as buildings reopen for daily use.

State officials have made general recommendations that ventilation systems be in good working order before schools reopen, but offered no specific targets. The Vermont Occupational and Health Administration, meanwhile, says it has no jurisdiction over non-mandatory guidance.

Federal public health authorities have offered little help. A Harvard University health project says it had to create a standard for high-quality ventilation in the pandemic — changing the air completely inside a room five times an hour — precisely because others hadn’t.

The problem surfaced in the Southwest Vermont Supervisory Union in Bennington, which hired an engineering firm during the summer to take a look at its ventilation. The news was not good: The systems in several schools, including at Mount Anthony Union High, were basically nonfunctional in large swaths of the building.

Alarmed that teachers were expected to report to work in person before recommended work was completed, Meaghan Morgan-Puglisi, a math teacher at Mount Anthony and a building representative for the local teachers union, filed a complaint with the Vermont Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

“Your description of hazards are not within VOSHA’s jurisdiction,” a compliance officer wrote back to Morgan-Puglisi. “I have included the below links which identify employer considerations regarding ventilation systems, but it is not mandatory at this time that your employer makes those updates,” he added.

School reopening guidance written by the Agency of Education, in concert with the Health Department, recommends that schools clean their HVAC systems and ensure they are in proper working order prior to school openings. The guidelines also recommend that schools increase outdoor air ventilation and invest in portable air cleaners.

But none of it is mandatory. The guidance “contains both requirements and recommendations,” Agency of Education spokesperson Kate Connizzo wrote in an email, and HVAC modifications, the guidelines say, “should be considered.”

Stephen Monahan, director of the workers’ compensation and safety division at VOSHA, said his department can’t really enforce another agency’s nonmandatory guidance. And besides, he said, the guidelines offer few specific standards that a VOSHA inspector could measure to assess the risk.

“There is no standard that says you must have this many air exchanges per minute or whatever,” he said. “There’s no existing standards, and nothing that we could test for, because nobody’s identified anything that we could test for.”

Monahan said employers have a “general duty to maintain a safe and healthy environment.” But the bar is pretty high, and would likely involve a school district flouting the guidelines in a more general way.

“If there were no steps to protect people, deliberate indifference to protecting their staff, then that would be a violation,” he said.

‘It’s a really big shortcoming’

The federal Centers for Disease Control has also put little emphasis on ventilation in reopening guidance for schools. Experts have criticized the approach, saying it ignores the pivotal role the air we breathe plays in transmitting the virus.

At a Harvard T.H. School of Public Health forum held Tuesday, Joseph Allen, an associate professor of exposure assessment science at Harvard’s Department of Environmental Health, emphasized that “there are devastating consequences to keeping kids out of school,” and districts should do everything possible to bring children back for in-person instruction where community transmission is low.

But proper ventilation should be a key component of limiting risk, he said, and there are many relatively low-cost, easily implementable solutions available to schools, including simply opening windows and using portable air cleaners with HEPA filters.

Allen is the director of Harvard’s Healthy Buildings Program, which has put out a 62-page report outlining strategies for mitigating the risk of the virus in school buildings, as well as a detailed how-to guide for schools trying to assess the quality of their ventilation.

The Harvard public health project recommends that schools aim for a standard of five air change rates per hour, which would mean that the air in an indoor space is replaced completely every 12 minutes. Allen noted that his team had had to create that standard because public health authorities hadn’t.

“It’s really a big shortcoming. The CDC never put out a standard. ASHRAE, the standard-setting body for ventilation, did not put out a number. When you start talking to schools, they say: What number should we target?” he said.

There has been no substantial federal investment in K-12 facilities in decades, and a majority of America’s public schools need major work, according to a federal watchdog report issued this summer. That’s had a substantial impact on the debate over reopening schools, and poor ventilation, in particular, has emerged as one of the thorniest problems to solve and a frequent flashpoint in negotiations.

Under pressure from the teachers union, school officials in New York City inspected and released ventilation reports on every school in the district ahead of reopening for in-person instruction.

The Vermont Legislature has already sent $6.5 million in federal relief dollars to schools to fix and upgrade HVAC systems, and lawmakers are poised to double the state budget they are about to pass. Hundreds of schools have already applied for the funds.

The Southwest Vermont Supervisory Union is working with Efficiency Vermont, which is administering the state’s ventilation grant program, to try and find money to pay for the work recommended for its schools. But for now, Efficiency Vermont has told them they’re tapped out.

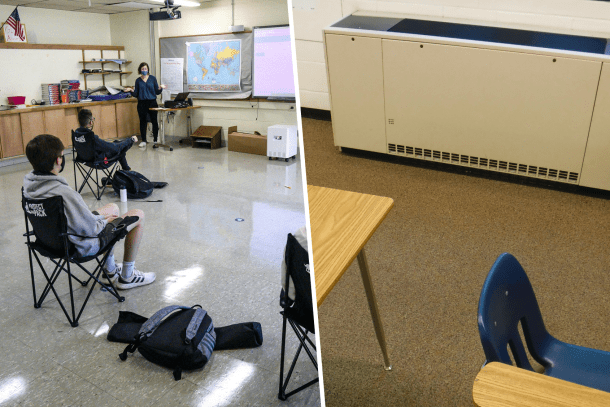

In the meantime, the supervisory union has spent about $25,000 out of pocket for stand-alone air cleaners, superintendent James Culkeen told the school board last week, and 54 units are set to be sent to the high school. Wherever possible, the schools also plan to open windows.

Southwest Vermont schools began the year remotely, but in-person instruction on a hybrid schedule for the majority of students is set to begin next week. Morgan-Puglisi says she just wants to know that buildings will be safe by then, but worries that the discretion afforded individual districts means that not everyone will opt for best practices.

“I think that if the state had mandated certain things, particularly around ventilation and air quality, this could be something that both VOSHA could help enforce and our schools would know what the minimum requirements are,” she said.