“Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto,” or “I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me.” —Terence, Roman playwright, circa 160 B.C.

And yet…

There is one true villain in this story; he died by his own hand, in 2005.

There is, praise God, a hero. Only one.

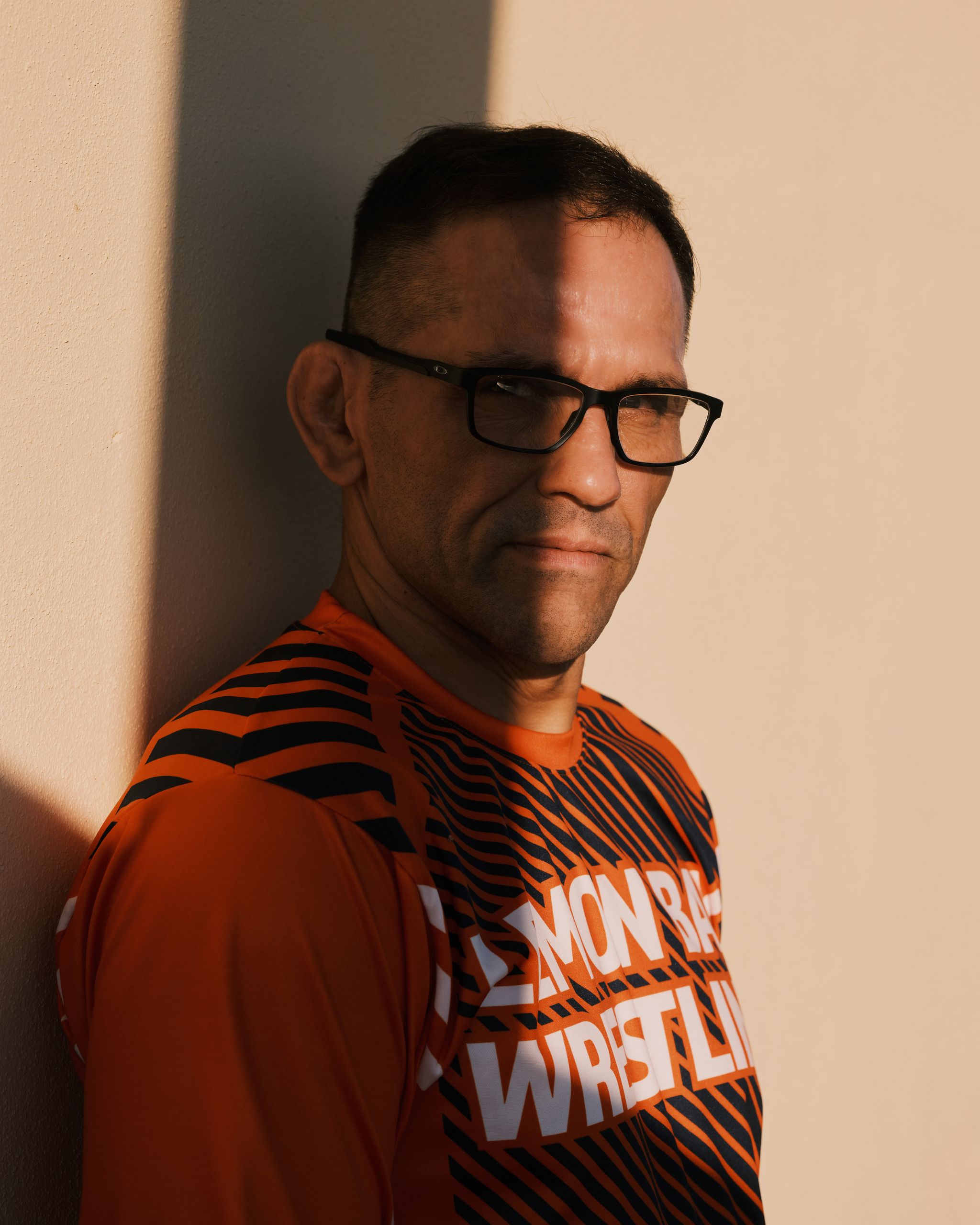

Like every wrestling coach, Mike Schyck’s a lifer, beginning on a basement mat at age five, getting mauled by big brother Doug, both of them coached and drilled by their dad—himself a wrestler, of course. Mike’s in his early fifties now, a five-foot-ten brick in a navy-blue track suit. He kept wrestling, and winning titles, into his forties, at international meets in Europe.

“Budapest and Sarajevo—everybody over there had cauliflower ear,” he says. “The grocery clerk, the female bank teller—everybody’s got cauliflower ear. Everybody was friends. You’re around all that, you’re in, you’re part of the family. They don’t know about headgear over there—it’s a mark of who they are.”

Mike’s got the ears: deformed by years of blunt trauma, bulbous, mottled, cartilaginous, incurable, and a badge of honor among his warrior cult. When I went to see him last winter he was coaching at Lemon Bay High, his alma mater, halfway between Sarasota and Fort Myers, in Englewood, where he was also fitness director at the local YMCA. He won two Florida state high school championships here for the Manta Rays, went 68–0 as a senior, and took a full ride to wrestle for Ohio State University. At OSU, he was a two-time All American at 158 pounds—among the top eight in the nation at that weight in 1992 and 1993.

He goes 175, 180 now, a lantern-jawed, close-cropped battering ram huddled with his team in the far corner of the gym, a red stress ball squeezed in one clenched fist.

“I’m just gonna treat you guys like soldiers,” Mike tells them. “You guys that are thrown into a varsity lineup gotta chalk it up as taking your lumps.”

Today’s the district duals and he’s shifted two of his wrestlers to a different weight class because his star—his son Lance, a 170-pound sophomore ranked fourth in the state—can’t go today: He’s in concussion protocol after getting dumped on his head in a meet last week. Lance is Mike’s reason for coaching. More than anything, he wants Lance to be the national champion Mike never was.

“We’re gonna need your best today—you need to flip the switch and fight. There’s nothing wrong with a little bit of fighting, guys. It shows me that you care. Caleb and Tucker—you guys got into it at practice. You guys were throwin’ each other into the corner, throwin’ punches and screamin’ at each other like you were sailors. It was good. You’ve got six minutes to fight, guys—go and fight.”

He’s not a shouter; he’s an urger, and the way he says “guys” makes him sound like a kid himself, but those three syllables—go and fight—are in no way metaphorical. This is a credo—truly all you need to know before you sign the permission slip for your own kid to go out for the school wrestling team. It’s a fundamentally different sport, unlike anything offered outside of a martial-arts academy or juvenile prison: Your little gladiator is signing up to do literal battle with someone else’s child, one-on-one, nearly naked. Wrestling is combat, hand-to-hand, ancient in its lineage, mythic in its viciousness, ferociously demanding. No stick, no ball, no hoop, no net: you and your opponent in the circle in the middle of the mat.

The rules evolve; not so the code: fight or flight. As any little brother can attest, wrestling and sprinting are the two original sports. We are, despite cologne and flush toilets, animals, and the code is ineradicable, embedded in our genes, as crucial to human survival as reproductive sex.

Nobody looks scared in a singlet and headgear. The kids look ready. Hungry. Savage. It’s a four-hour slopfest, complete with toddlers who pair off on the mat to scrap after each dual pairing ends, wrestlers’ moms howling, “PUT YOUR CHIN IN HIS CHEST,” and plenty of sudden reversals and quick pins.

Without Lance, Lemon Bay finishes second among the eight teams. Mike spends the long afternoon crouching, barking instructions through his cupped hands, bounding from his metal chair at the corner of the mat at some point during nearly every match, hopping and high-fiving after wins, and going jaw-to-jaw with one referee, another lifer Mike’s known since they were kids. Afterward, he and his boys roll up and stow the mats.

“I know it’s not what you wanted,” he tells one red-eyed newbie, “but remember—it’s going to get better. You’re taking your lumps and it’s gonna get better—I promise. See ya tomorrow.”

He makes his way through the empty hallways and the back doors, texting as he walks, to where his car is parked. Mike’s okay with today’s result, considering his son’s absence.

“Lance would’ve pinned the kids he would’ve wrestled in ten seconds. You know what’s kind of cool, though? I’m having fun coaching guys that have no idea what the heck they’re doing. You want them to see success, but I started doing this at five—by the time I was ten, you start knowing how to move, how not to move, how to position yourself. Wrestling is a language.

“Kids don’t know certain things to do—‘Oh, maybe I do gotta go to fighting’; ‘Oh, maybe I can punch him in the back of the head’; ‘Oh, maybe I can push him out of that small little circle in the middle of the mat’; ‘Maybe I can make him feel like he doesn’t want to wrestle anymore’—you get to that point where you gotta learn how to fight.”

Fear. Fear and pain and suffering. Enduring it, mastering it, and, above all, inflicting it. Legendary coach Dan Gable—’71 world champ, ’72 gold medalist, Zeus of the sport—once told me, “You train combatively, not just technically. You hit heads and hit heads and hit heads. My opponents knew it wasn’t just going into a wrestling match—it’s going into, ‘HEY, this guy’s gonna drudge me.’ People were scared of me when I wrestled. There’s a fear there—and that’s what I want.”

Like every other wrestler his age, Mike wanted to wrestle for Gable, who coached at the University of Iowa. He and his brother trained at Gable’s monthlong summer camps when they were coming up. Mike set up a visit to UI when he was deciding on college, but a Hawkeye assistant coach told Mike a full scholarship wasn’t in the cards. Gable himself phoned to follow up; even now, he speaks of it with wonder.

“I’m nervous, I’m shaking, I’m talking to Dan Gable. He said, ‘We’d love to have you still come.’ I’d already been to Iowa, I’d gone to camps there every year, so it wasn’t something I needed to go see—I knew all the coaches. So I went to Oklahoma and Lehigh, then Minnesota—and when I came back from Minnesota, I told my folks, ‘That’s where I want to go.’”

But Mike also had an Ohio State recruiting visit scheduled, and his folks encouraged him to check out the campus. He loved it, the coaches loved him, and Mike ended up a Buckeye.

Mike shares a Gable story, passed down by his OSU head coach, Russ Hellickson, who wrestled in Bulgaria with Gable in the 1971 World Championships; Gable won, Hellickson finished third. When the team bus was leaving the hotel the morning after the tournament ended, Gable was nowhere to be found.

“A couple hours later, they see him running in sweats outside of the hotel,” Mike says. “Russ asked him what the heck and Gable tells him, ‘I’m not here to win a World Championship—I’m here to win the Olympic gold.’”

The Russian coaches watched Gable win that championship in Bulgaria, skulked back to the Motherland, and engineered Ruslan Ashuraliyev, a 68-kilogram wrestler programmed specifically to beat Dan Gable at Munich. Gable shut him out. In six matches on his way to the gold, he gave up no points. Zero.

The parking lot’s dark and deserted. Mike asks me back to his house to talk some more—because we’re not here to swap Gable fables or talk high school wrestling. His cell chimes—a text from his Manta Ray heavyweight. He reads me the thread.

“I texted him, ‘Great job today—proud of you, big guy.’ He just replied, ‘Thanks, Coach. I couldn’t ask for a better coach and a second dad. I wouldn’t want anyone else in my corner. You mean a lot to me.’

“Think about this,” he says. “What he just said to me is what I said to my college coaches. Imagine if I would betray him in a way like that—and not do anything? I wouldn’t do that. I wouldn’t hurt that kid. No way.”

I love wrestling. Not pro wrestling, no, not since Bruno Sammartino was The Man, when I was ten. I love sport, and loathe soap opera. Sumo, yes; a crazed half ton of fun. Greco-Roman, for sure, though I watch it only when the Olympics roll around. What I truly, deeply dig is folkstyle—collegiate wrestling.

I’m strictly a fan. I’ve wrestled with self-doubt, addiction, and words all my life but never had the sack to strip, don a singlet, and grapple. I came to adore college wrestling in my thirties, in Iowa City, where I did grad school. I got there in 1984, not long after the University of Iowa Hawkeyes had won their seventh straight NCAA Division I wrestling championship. They won in 1985, too, and in 1986—nine straight, two more than John Wooden’s UCLA basketball teams. At that point, I—a Cleveland State alum wholly unaccustomed to any sports team I gave a damn about winning any meaningful thing ever—was still a wrestling ignoramus. College sports meant squat to me.

Then I met Dan Gable. In 1987, I began to write a weekly opinion column for The Daily Iowan, the UI student paper. I was no journalist—I had a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, a dime a dozen in Iowa City, just one more short-story writer working on what was never to become a novel. The columns paid $25 each; the pure joy of pissing off thousands of sweet Iowans every week was priceless. Gable was the Hawks’ wrestling coach. I knew he’d taken gold in the 1972 Olympics, in Munich, where Palestinian terrorists had massacred eleven Israeli Olympians.

I included Gable in a column about the school’s coaches after he was quoted as wishing he could use a cattle prod on his wrestlers. He spoke of “inflicting new levels of pain” on the young men he coached. I called him “Der Fuhrer” in print. And then I got a query from an editor at the late, lamented Sport magazine asking if I’d profile the coach as he bulled his team to their tenth straight crown, in exchange for a real-writer paycheck.

I was eager. Gable was not. It took two sit-downs in his office at Carver-Hawkeye Arena to convince him that I was only 98 percent asshole. Maybe he even respected me for facing him mano a mano, because nothing else explained his eventual willingness to say yes. On the way out of his office after giving his blessing, he tossed me a roll of tickets for the upcoming season—a gift that any experienced journalist would’ve refused. Not me. I didn’t miss another dual meet at Carver-Hawkeye until I moved to Philly in 1991. My Gable profile ran in 1988. Naturally, the Hawkeyes’ title streak ended that season—one shy of ten straight—because Cleveland.

I learned a lot—about focus, about hard work, about pushing myself past what I thought were my own limits—from studying Dan Gable. So did John Irving—another UI MFA, an actual wrestler and a real novelist. Irving wrote about him for Esquire in 1973, in “Gorgeous Dan,” which described in splendid detail what it felt like to get out on the mat to grapple with the man himself.

“When Dan Gable lays his hands on you, you are in touch with grace,” Irving wrote.

But Gable’s not the hero here.

When I park my rental car in his driveway, Mike’s already inside. When I get out, I see a big snake stretched out between me and his front door. Four feet long, maybe five—it’s not moving. My sphincter clenches, hard. My loins tingle. I don’t ask myself what Dan Gable would do; I call Mike’s cell.

“There’s a snake in your driveway,” I tell him.

“Really?”

“Between me and your front door.”

“Okay.”

“Mike—would you mind coming out and getting rid of the snake?”

“Sure.”

He comes out with a broom. The snake’s dead; he sweeps it to the street as I mince past.

“I must’ve run it over when I pulled in the garage,” he says when he returns.

The living room’s dark. Mike lives alone; he’s divorced. He takes the sofa. I grab a chair across the room next to a side table where a lone lamp’s lit and plug in my recorder. He starts talking and doesn’t stop for two hours and change. No drinks, no snacks. In a voice still stuck in another time and place, Mike pours all of it out.

“First week on campus, we go through our meetings—compliance with the NCAA, team meetings in the wrestling rooms, finding my classes, and then we got to go do a physical. I’d been a week on campus and we go off to the Woody Hayes complex. You basically made your way—they had stations—to where Doc Strauss was, a room about half this size. He’s sitting at a desk on a rolling little seat. He’s got his back to you and he reads your chart and he’s ready to go—he rolls himself over and checks your ears, the tongue depressor, that whole thing. Then he rolls back to his desk and tells you to drop ’em from across the room.

“He tells me to drop ’em, and you’re standing there, and he wheels his way over to you. He’s 125 pounds and you could break him like a balsa stick. His face is right next to your junk and he’s got his hand on your dick for at least five minutes, trying to get you aroused, lifting it, pulling it, tugging it, the whole nine yards, making casual conversation with you the whole time, asking you personal questions while he’s doing it—‘You have any problems, any issues?’

“At that point I’m frozen in time. You’re trying to do one of those things like you don’t want anything to happen—God knows you don’t want to get a hard-on. So you’re doing everything you can and he’s still doing his deal on it. He’s got his hand on your butt cheeks. He’s grabbing your leg. It’s like he’s there doing the deed as a girlfriend—he’s trying to do everything he can to get you aroused, and while he’s doing that, I don’t know why, but I ended up telling him I got hit in the privates. I got hit in one of my nuts and I got a fluid-filled sac, like a bruise.

“I’m talking to the doctor, but I just shot myself in the foot because now he goes and wheels himself back to his seat. I’m scared as hell—he turns the light out and he’s got a light pen and he starts rolling my way. I can see him coming with the light pen over to where I’m at, and then he does the same thing on me again with the light pen and it gives him the liberty to go even deeper into what he’s doing. He’s lifting, he’s pulling, he’s prodding, he’s pushing, he’s grabbin’ my nuts—I mean, I’d never had anyone do that. Never had a girlfriend do that. He’s putting a light on it and he’s doing this and he’s doing that and he’s showing me and he’s grabbing the head of my dick and pulling it up and down—that was my first time with him.”

Mike stops talking for a few seconds that seem like forever.

“My first physical. I’m a freshman. Take that as an eighteen-year-old. You’re on full scholarship and you’re trying to find your way with new teammates—you think you’re gonna be that guy that’s going to say anything? You think you’re going to be the guy that’s gonna make yourself look like you’re a fool? Now, in hindsight, I would have screamed from the top of the hills, ‘What the eff is going on?’ No one did. So that’s what I dealt with. The first week on campus.

“As you’re going into the room, a lot of the upper classmen, they’re doing catcalls—they already know what’s happening because it happened to them the year before and the year before that. They’re already doing the catcalls—and I’m a freshman listening to that. I didn’t know this till I got out of there, but if you’re in his office a longer period of time than everybody else, what do you think you got when you came out? The catcalls were even worse. ‘Oh, Doc Strauss loves you now. HE LOVES YOU. You are the guy. You’re his new boyfriend.’”

Dr. Richard Strauss spent twenty years at OSU; hired in 1978 as an assistant professor in the College of Medicine, he volunteered his services as team physician eagerly, eventually became associate director of the Sports Medicine program, and retired with emeritus status in 1998, after having sexually assaulted at least 350 male athletes—including 47 allegations of rape—across at least fifteen different sports. University officials in the Sports Medicine program and the Athletics Department first received complaints about Strauss’s misconduct in 1979 but did less than nothing to stop him. Truth is, as he carried on—and as the number of complaints about his predation grew—university officials dealt with Strauss by promoting him until he came to enjoy access to every sports facility and team on campus, and was also given free rein at the Student Health Center, where he sexually abused nonathletes, too.

In 2005, he killed himself.

That’s that. His life holds no meaning but the damage that he did.

“When I graduated from Ohio State, I had the fourth-most wins in the history of the program. I was like, ‘I’m going to make the Olympic team’—and to do that you had to be reliable and stay healthy. I knew that I couldn’t sit out at all if I was ever gonna accomplish my goals. So you sit out and not get treated, or you go and get Dr. Strauss to help you. So what’s the lesser of your evils—do I stay injured or do I go see the guy who can help me? I wasn’t a hypochondriac—I had to go to see him for everything under the sun. Everyone on the wrestling team probably at one time got herpes—anytime I got something close to a pimple or zit, what do you think I did? I went to see Doc Strauss—and what do you think Doc Strauss was doing to all the athletes when they went in? The first guy that was reported in 1979 went in for cauliflower ear and he ended up getting a genital check. Every time I would go in there, what do you think I got?

“You needed any type of medicine, you go into this little office, and you’ve got a whole pharmacy—he’s got all the things. If a lot of the guys were having ailments, like the herpes—it was a skin thing that everybody got. If you didn’t get it treated, it spreads. What do you do? ‘Doc, I need help.’ So it was a trade-off. Guys that were in deeper—there were guys on the team that if they didn’t want to go to class, what do you think they did? Got a note from Doc. He gave them a note—but what do you think happened as well? You turned a blind eye to the things that were happening, and it gave him a little more control.”

“If you were in our locker room—and this is before the physicals happened—Dr. Strauss groomed you through what he had at his disposal. He had a locker in our private wrestling locker room. We would practice at 12:00 and go to 2:00. As soon as we were done, he would be in our lockers, undressing and going into the shower, taking a shower with everybody. Every day. It didn’t matter if he was clean, dirty, or whatever, he’d be in there taking a shower with you. But here’s the kicker: Everyone would be facing the wall doing their thing; Dr. Strauss would be watching everybody. That’s what he was doing—he’d be showering and watching everybody, at times with a hard-on. And then he would go back into the locker room, then out the door of the locker room and into the next door down, a private locker room for the gymnasts. He had a locker in the gymnasts’ locker room as well.

“I don’t know at what level that he had administration by the balls, to allow that to happen, because if it was so rampant that people had complained and nothing was done, it’s gotta lead you to believe there was a reason why. Was there leverage over the administration? Why didn’t his boss—why didn’t some of these other people—say something?

“I drank the Kool-Aid, my family drank the Kool-Aid—you’re going off to a university where they’re gonna take care of you—and there was harm. There was harm that was done. And there are important people that have an opportunity to be responsible and speak up—and they’re not doin’ it. The problem in this whole thing is that people didn’t stand up and say anything—they kept mum. And they’re keeping mum now. And it pisses me off to no end.”

A former teammate contacted Mike in May 2018, asking about his experiences with Dr. Strauss, then asked Mike to participate in a whistleblowing video he wanted to send to OSU, documenting Strauss’s abuse. Mike said yes, and after news of the scandal broke, he spoke publicly about Strauss in November 2018, at an OSU Board of Trustees meeting. After the university’s lawyers asked a judge to dismiss the first Strauss-related lawsuits because the statute of limitations had expired, Mike testified at the statehouse in support of a bill extending the statute for Strauss’s victims; meanwhile, as a plaintiff in one of those suits, he endured psychiatric exams, depositions, and ongoing meetings with a court-ordered federal mediator. (The lawsuit is ongoing.)

“That whole victim thing, it was new to me. It consumed me. People say, ‘Oh, you’re gonna be fine—once you get to the other side, you’ll be fine.’ But you still have those feelings of guilt and shame—you were in the midst of all these guys, and the way you coped was just by laughing it off. As an adult, you know things—you’re smarter, you’re educated. You start dealing with the thought that you should have done things differently. I had to sit with a psychiatrist and get evaluated—that was the most emotional thing I’ve ever been through in my life. They wanted you to go back and remember from when you were zero to six, six to twelve, twelve to when it happened—you put the pieces together. The hurt from the past, the hurt from the present—I see it more now, because I’ve had to.

“As an athlete, you’re taught not to be a victim. You figure it out, you problem-solve, you do what you gotta do to make it right. You get better. You didn’t do anything—you didn’t speak out back in the day. Maybe by speaking now, I’m righting the wrong of the past for me. I feel like I’m dealing with everybody’s stories—not just what Strauss did but how it’s affected them, the abuse, the emotional toll that they’re expressing as an adult. I’ve got this baggage on me—I feel like at any turn I could start tearing up and crying. I’ve heard so many of my friends’ stories, and they pile up. I’ve cried in the statehouse. I’ve cried in front of the Board of Trustees. I’m like a sieve, the water just comes out—it almost leads to people thinking you’re not a strong dude.

“This is why you need to scream it from the top of the mountains—because what we’re dealing with right now is actually more damaging in a way than what happened back then. Just being a part of it, the collateral damage—when this first came out, a coach here in town, big Ohio State guy, he said, ‘You’re nuts—you’re gonna be part of that MeToo movement?’ This isn’t us tryin’ to take down Ohio State. I lived it for eight years; I’m not the problem. ‘Well, whaddaya want?’ Are you kidding me—is that your response? How about, ‘I’m sorry that ever happened to you’?

“It hurts. I bled scarlet and gray. I stayed on as a volunteer coach going through graduate school, so I was there for another three years. I’ve invested in that school. And to know I’m in this position, trying to get accountability for something that happened—and people knew and did nothing about it against a university that I loved dearly. I’ve been a mat rat my entire life. I come from that ilk, like the Iowa guys. I’m a tough son of a gun. I almost feel like God put me in wrestling because you had to be tougher than hell and disciplined. It was my training ground for all the crap I’ve had to deal with this stuff.

“People out there are so ignorant. When this first came out, people were saying this is BS—‘Why didn’t you just fight the guy, punch him?’ Or, ‘If you’re lettin’ him do this, then you’re gay.’ One of my friends that I’m not friends with now, he wrote, ‘Mike is a self-professed sexual abuse victim from the ages 18 to 26—in my mind, that’s consent and Mike needs to come out of the closet.’ Quote, unquote.

“I don’t want anybody to take the one thing that was really meaningful to me in my young life—being a college athlete at a major university and doing what I did—I don’t want anybody to even diminish that in any way. I don’t look at Ohio State through the perspective of this Doc Strauss stuff. As much as I’m mad at the way Ohio State was dealing with the abuse, I’m looking at it as the people doing it, not the place where I did what I did—that’s the way I get myself to look at Ohio State, so there’s a good feeling in my heart over all that.

“You’ve gotta live with yourself, and the thing I want to live with is—like I’ve always done in my life with everything—to try to do it the right way. I chose to speak. It’s sad, because the eight years I was there was the best time in my life in many ways. It was a crappy thing we all dealt with. It was horrible. We coped in the only way we knew how as kids. But we’re taught in college and we’re mentored by people that are highly moral—and they told us about integrity—doing the right thing. When they were faced with it, they didn’t do it. I chose to do it.”

INTEGRITY. Mike has the word painted in capital letters on a wall in the high school wrestling room. Words are easy to paint on a wall. Living honorably in a fallen world is harder. I came to meet Mike because I was shocked and riveted as the Strauss revelations unfolded. Not because one more adult male university official, with a modicum of power over teenage athletes and his own colleagues, sexually victimized hundreds of youngsters for decades on a sprawling campus; same thing happened at Penn State, Michigan State—not to mention the Catholic Church and the Boy Scouts of America. It’s always and forever the same story: Children are not abused by monsters; they’re physically violated by their doctors, coaches, teachers, and priests—by the trusted men who lead them, men who crave sex with them, lusting for control and power over everything but their lust.

Monsters? Calling them monsters not only reveals the fear, shame, and lust in our own human hearts, but also our cowardice. For every so-called monster, how many non-monsters knew but looked away, knew but did and said nothing—everywhere and every time this systemic sexual abuse occurs? Are we so blind, so dumb, so terrified of telling the truth, even now, even to ourselves?

Nah. I was shocked only because dozens of Ohio State University wrestlers were among the Strauss victims. Wrestlers? Get the fuck out of here.

Yessir—wrestlers, too. Because if the story’s always the same, regardless of gender or geography; if the athletes are young, inexperienced, and trained to trust their coaches, to submit—body, mind, and spirit—to authority; and if those men who groom, seduce, and rape them are too sick to stop themselves; and if all the knowing, silent bystanders—whatever their paltry, selfish reasons—choose to leave the victims at the mercy of a sex dragon: Then why not wrestlers?

But that’s not truly why I visited Mike Schyck. I wanted to meet a former OSU wrestler because of another former wrestler, at the University of Wisconsin in the 1980s, Jim Jordan. Jordan was no Dan Gable, but he’s a legit Hall of Famer, a two-time national champion at 134 pounds who came to Carver-Hawkeye Arena with a so-so Big Ten wrestling team and kicked ass—a gritty kid, a redneck ginger from the southwestern Ohio sticks, another human machine built for mauling.

I can still see Jordan on the mat, in Iowa City and Oklahoma City, where he won his first title with a 7–4 win against Okie State’s top-ranked John Smith. Smith became a world and Olympic champion; Jordan became a congressman from Ohio’s Fourth District, cofounder of the Freedom Caucus, and Donald Trump’s favorite takedown artist.

But long before Jim Jordan became a politician, he came with Russ Hellickson, his college coach, to OSU, where he trained for the 1988 Olympics—he didn’t make the team because John Smith whupped him—and served as an assistant coach for eight years. Jordan was Mike’s mentor.

“There were other coaches around the team, and they each had their own little niches, guys they glommed on to. I wrestled Jimmy pretty much every day and got my ass handed to me on a silver platter. I hadn’t gotten strong yet. I weighed about 175, he weighed 150-ish, and I mean he beat the livin’ snot outta me.

“I would finally just say, ‘Take me down, I don’t care’—I can’t even hold my arms up, I’m so tired. And he would pin me up against the wall. If he took me down and I landed on my back and I would tap him on the back to let me up, he would jump his chest up toward my mouth so I would actually start having to try to figure out a way to breathe and move. Jimmy would take me off the mat. He would let me know that if you do it again, I’m going to take you farther. We may be at the water fountain. We may be in the bikes.

“It was every bit of what was needed to get better. I was okay with being pushed and being challenged and going through a lot of suffering. Did I like what was happening? No. But now you’ve got to problem-solve—if you want to get better, then you’ve got to figure it out. What Jimmy taught me was that you just gotta fight. You gotta fight. That’s college wrestling for you, at its best. Jimmy was the coach that everybody knew. He was like Opie Taylor from Mayberry. Everybody respected him and looked up to him because he was a high-moraled Christian guy and every bit of what you would hope to be like. Going to Ohio State to wrestle with guys like Jim Jordan was my choice. Jimmy was a huge influence on my life, and I owe a lot of my success to him.”

Integrity and politics have little to do with each other—these days, absolutely nothing. Watching the impeachment hearings, watching Jim Jordan, fifty-six years old and a grandpa now, I saw the very same panther I watched at Carver-Hawkeye attacking an opponent without relent or regard for anything but winning. And my own political views are such that there’s no bone in my body that does not loathe Jordan to the marrow. I retired from Esquire in 2016 and that was fine with me, because after nineteen years in these pages, I’d said everything I had to say, some of it too many times, and yet I could not resist this story—not if it meant passing up a chance to grapple on the page with that short-sleeved Cro-Magnon sack of scum.

And yet: Integrity and journalism should have something to do with each other, even— especially—these horrid days. I didn’t look for an OSU wrestler who shared my politics or my enmity toward Jordan. I wanted to find someone who didn’t, and who’d help me grasp what happened, how it happened, and why it keeps on happening, even to the toughest guys I’ve ever met.

This much I know: I found a hero in Mike Schyck. Not just because he saved me from a dead snake but because he knows that integrity, not politics, defines a man’s character, and because he knows and is unafraid to speak truth about what happened at Ohio State—the how and why of it—and because none of that broke his spirit or hardened his heart.

Mike’s former teammate who produced the whistleblower video also asked Russ Hellickson and Jim Jordan for their support. Hellickson agreed, and the eleven-minute clip—The Scarlet X—that Mike shared with me features Hellickson, Mike’s head wrestling coach.

“When I came in to Ohio State in 1986, Dr. Strauss was our team doctor—but he was always too hands-on.…He would come and watch at the time our guys showered, a lot.…I know it went on in other sports too, not just wrestling.…It became a real problem because it affected the mental state of a lot of our wrestlers…certainly all of my administrators recognized that it was an issue for me.…I know I had a lot of conversations…about it, but nothing ever changed.”

Congressman Jordan, rather than taking part, used the heads-up to hire a public-relations firm to get ahead of the story by rounding up statements from former OSU wrestlers and coaches willing to vouch for him and smear his accusers. He also made the rounds at Fox News to attack the Seattle law firm OSU paid $6.2 million to investigate the Strauss allegations, with the de rigueur accusation that they were allied with the Deep State, the Steele Dossier, and—of course—Hilary Clinton.

“I never saw, never heard of, never was told about any type of abuse,” Jordan told Fox. “If I had been, I would have dealt with it.…A good coach puts the interests of his student-athletes first.”

The PR firm squeezed a statement out of Russ Hellickson, too:

“At no time while Jim Jordan was a coach with me at Ohio State did either of us ignore abuse of our wrestlers. That is not the kind of man Jim is, and it is not the kind of coach that I was.”

Having studied the redacted version of that $6.2 million report, all 232 pages and 711 footnotes, and having watched and listened to him on the whistleblower video, it’s clear to me that Russ Hellickson tried to get his bosses interested in protecting his wrestlers. As for Ohio State University, they’ve offered to pay for counseling for the Strauss victims, settled lawsuits for tens of millions, and refused to support a bill that would help Strauss’s OSU victims seek redress by extending the statute of limitations; that legislation, modeled on a bill Michigan enacted after the sex-abuse scandal at Michigan State University, has been stuck in the Ohio statehouse for more than a year.

Russ Hellickson ignored my requests to talk about Mike’s story. I had a single off-the-record phone call with a spokesperson for Congressman Jordan, but nothing came of it. (I also emailed Dan Gable for his perspective, and to tell him that I wasn’t writing a story that dishonored—or blamed—the sport: nada.) Hoping to snag Gable or Hellickson, I went to the B1G conference wrestling championships at Rutgers University last March, but all I caught was a blessedly mild case of COVID-19 and a chance to see Rocky Jordan, Jim’s nephew, wrestling for Ohio State. Rocky finished fifth. OSU finished third. Iowa kicked everyone’s ass.

“I would love to have a conversation with Jimmy,” Mike says. “This is not a political thing. My politics don’t fall too far from his—I’m a conservative. I almost feel bad he was brought into this. He didn’t do the abuse. But he ended up reaching out to have wrestlers vouch for him—there’s never been a call to any of the wrestlers to find out, ‘Hey, what can I do for you?’ or ‘How you doing?’

“He would have been like Superman to the guys he has mentored and coached by just saying, ‘I know what you guys are going through. It was a horrible environment.’ Just something. Then it would have been gone. It would have been put to bed. He had the opportunity to do what a lot of people didn’t do back then and aren’t doing now. That’s to step forward and say something.”

We’re in his office at the Y, a small cubby tucked just behind the front desk. In lieu of a door, Mike has a large scarlet Ohio State curtain draped across the entry. The walls are plastered with photos, mostly of Lance and his daughter Faith, a D1 soccer player recovering from ACL surgery. Plenty of Buckeye memorabilia, too, including a team photo of the 1989–90 wrestling team—Mike and Jimmy included.

“My mom asked me a number of times, ‘Did you tell Russ and Jimmy?’ I can’t say that I did. Telling somebody something, it implies that they didn’t know. When you’re a part of this with everybody, everybody knows about it. Right next to my locker was Dr. Strauss. And two lockers to my right was Russ and Jimmy. These guys were privy to who Dr. Strauss was and what he was all about.

“I talked to Russ three or four times a month since I got out of college—I haven’t talked to him in two years. I want to ask Russ, ‘Why was it that he had a locker in our locker room? Why does a doctor need to come shower with us? This is your wrestling program and your locker room—why are you allowing it? Why didn’t you tell him to get out?’”

I ask Mike if every wrestler at OSU was required to get an annual physical, including Jordan.

“Oh yeah—I think Jimmy Jordan did, too. I don’t know if he did. But I would bet that he’s gone in there to see Doc a number of times. I would bet everything I own.”

I ask him how his own kids feel about him going public about what happened to him.

“When all this broke—my daughter, I was talking to her about it. I sat in the parking lot while she had to go get her physical. I told Faith, ‘You have a voice. Don’t let anybody manipulate you. If you feel something’s not appropriate or something’s not right, you speak up—and I have your back in every way, shape, and form.”

And Lance?

“Early on, I kept it from him. I think he knows about it now. Maybe he hears it too much, but I think he’s proud of me. I’m hugging all my wrestlers—I wasn’t like that as much the past couple years. I try to do that more, maybe because it feels good for me but also because I think some of these kids got hurt in their life. I want my guys to be loving. I want to continue to be the best version of who I am. I’m proud of myself. If I practice harder than anybody else, I’m going to get better and better and better.”

As codes go, Mike’s recipe—practice hard, get better—will do just fine. It requires fighting, not fleeing—fighting like hell for truth and integrity and justice. Wrestling through our distress and pain, living with hope, takes courage and honesty. Talk, especially about these things, is cheap.

We live lives immersed in—driven by—codes, genetic and self-generated. We’re the species suffering life with the certainty of death, the species that creates gods who command us to honor our own parents, to not kill and otherwise afflict other humans, to pray and kneel to a higher power with no actual power or demonstrable concern for anything we do. If the word of every word-of-God screed boils down to “Love Thy Neighbor,” then the fundamental truth embodied therein is that we, left to our natural state, are disinclined to do so. Strongly. Perhaps, on the basis of available evidence, irredeemably.

And yet we strive, or we pretend to.

“A good coach puts the interests of his student-athletes first,” said Jim Jordan, who stripped and showered every day in the same locker room as Mike Schyck and Dr. Richard Strauss, who put no expiration date on his coaching code, who now claims he knew nothing.

That’s not sexual abuse, not politics, not something that happened long ago and far away.

That is betrayal.