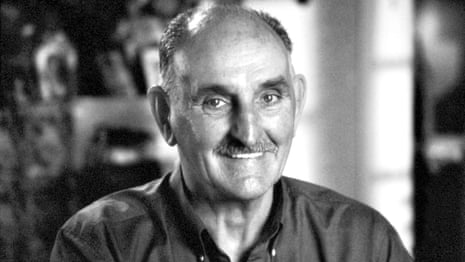

The poet Bruce Dawe, who wrote his first poems in his teens under a pseudonym, has died at age 90 as one of Australia’s best-known poets, respected by a wide and diverse audience. This diversity would have mattered to him. His work was widely honoured in his lifetime, including with the Patrick White award and a Christopher Brennan award for lifetime achievement in poetry.

From a working-class background with broken schooling in Melbourne, then later ongoing commitment to part-time education, through to receiving a PhD, he eventually became a teacher and academic in Queensland. Dawe’s earlier work experience (his many jobs included being a postman, working in a battery factory and serving for a long period with the RAAF) provided the “lived life” feel of social familiarity in his poems.

Born in Fitzroy, growing up in Victoria and spending time working in Sydney, Dawe eventually taught in various institutions in Queensland. Apart from writing many books of poetry, he also edited a poetry anthology, Dimensions, published fiction, and collated Speaking in Parables (drawing on Christian, Jewish, Buddhist, Islamic and Hindu writings). Though he was a social commentator on the secular, his religious sensibility often underlay his moral positioning toward the material and secular. In an interview I did with Dawe in 1998, he said, ‘“what we do is to deify the secular in one form or another, isn’t it?” That statement, also a question, shows something of his poetic practice, too.

For decades, when you went into a second-hand bookshop in Australia, even if there was no poetry section, you’d find at least one book of poetry, and that book would be Bruce Dawe’s Sometimes Gladness. It wasn’t simply about a discarded book looking for a new owner, but the inevitable circulation of a school standard across the country. Innumerable copies of the many (updated) editions of this timeless classic were in high-school kids’ bags, lockers, bookcases, desks and maybe scattered on their floors after a heavy study session.

At school in the mid to late 70s, I too studied Dawe’s poetry, and as I look through my bookshelves now I find three copies once owned by an in-law, by my mother and by a stranger whose school form number is written after their name – on top of whiteout, because underneath you can make out another name, and another form number. New editions with new poems came along, but at the book’s heart was a remarkable body of socially aware, socially critical and socially investigative poetry that had coalesced by the mid-70s.

Here was a poet who spoke with “the voice of the people” (or “a people”), who knew all the tones of irony and satire from the world he’d grown up in, lived in, and the world he saw beyond Australia’s borders. He translated the satirical ways of other literature into Australian contexts. I use the word “border” because Dawe’s 2016 collection, Border Security (UWAP), shows his ability to empathise with human vulnerability when faced with officialdom, with the trappings of power (what we do or don’t take through customs, and how such barriers work on our conscience). What are the real and imagined barriers between people?

Always behind Dawe’s seemingly playful banter with us, his readers and public, is his commitment to sympathy and connection with the less empowered, the disenfranchised, downtrodden, neglected and exploited. He differentiates between the human foibles shown and exercised by power, and those of people who have little or no power. Dawe wrote against tyranny, brutality and totalitarianism. He wrestled, sometimes subliminally, with issues of masculinity.

Yet it was also in his “topical” teachability that sometimes schoolkids missed out on Dawe’s lyrically tender side – where irony, pathos and excoriating acerbity are put on hold to show the gravity of personal loss, of the essence of living shared by all.

I will never forget a school lesson in which we studied A Public Hangman Tells His Love, a 1967 poem about the Ronald Ryan hanging in Melbourne, that works like a disturbed love letter or a paradoxical letter of estranging yet familial tenderness between executioner and victim. It shows not only the brutal wrong of state execution, but the way in which we can be affected by tone and expectation with seemingly “ordinary” language-use. That poem, written about what became Australia’s last “legal execution”, begins:

Dear one, forgive my appearing before you like this,

in a two-piece track-suit, welder’s goggles

and a green cloth cap, like some gross bee – this is the State’s idea ...

And this epistle, almost apostrophe, is signed off:

Be assured, you will sink into the generous pool of public feeling

as gently as a leaf ... Accept your role. Feel chosen.

You are this evening’s headline. Come, my love.

What Dawe achieves here is horrifying and deft at once – implicating not only the state, but all who acquiesce in this kind of treatment of another living being; always speaking about power, but examining the often compromised nature of the generic “public”. He appeals to our consciences by revealing our ways of dissembling.

At the end of that lesson, I was browsing his other poems to hand, and came across the remarkable 1964 lyric Elegy for Drowned Children, where Dawe’s rhetorical, conversational questioning mode becomes public and private in its implications at once:

What does he do with them all, the old king:

Having such a shining haul of boys in his sure net,

How does he keep them happy, lead them to forget

The world above, the aching air, birds, spring?

I understand why I was taught A Public Hangman, because of its “topicality” and moral gravitas and necessity, and yet I wondered how closely connected the two poems were: both concerned with disempowerment and all its complexities. Both seemed to come from the same psychological place.

And Dawe, though such a readable poet, a poet who speaks with people as if they will get him if they want to, also deals behind the screen of the page, with the personal behind the political.

Whether writing against the intractability and consequences of war in a quiet, understated but overwhelming way, getting at the root of the problem, or laughing with us about sports obsessions (Australian Rules Footy!) and group behaviours, he was always with us, and remains with us, the people, for all our (many!) faults. He can joke, laugh, cry and also be very angry. He can take us from the material to the spiritual, and be generous about it.

Les Murray once called Dawe “our great master of applied poetry”, and as Dawe said to me in that interview mentioned above: “Like many critics of particular things, I am half in love with the things I criticise at times; I know the appeal such media phenomena as TV have because I’ve felt it, too.” And in this, we have the key, just maybe, to why a Dawe poem can get us onside whether we agree with its gist, or not. Bruce Dawe’s passing is a great loss, but his poetry “of the suburbs” and further afield will continue to be relevant for a long time to come.