In 1920, after a long negotiation, the Italian state ratified the purchase of Palazzo Costabili in Ferrara – known as ‘the Palace of Ludovico il Moro’ because of a misreading that ascribed the property to the Sforzas. The pronouncement on the matter by the Council of State – an opinion requested by the Ministry of Public Education – had been clear: ‘built with the appropriate magnificence of a palace, it fell into private property, becoming a nest of misery and threatening to lose the last vestiges of its ancient and celebrated artistic beauty’ (Figure 1). Although the authorities were pleased to have claimed the palace as a heritage site, they had to contend with the cumbersome presence of a number of tenants occupying the building. The majority of inhabitants, in a broad (mis)interpretation of wartime Italian housing decrees, had stopped paying rent to the owners. Since they did not pay anything to the state either, they can be regarded as illegal occupants, or ‘squatters’. Soon after the purchase, the local inspector of monuments observed that while the move had ‘virtually started the redemption of the historical building’, it could not be denied that the first problem was the eviction of the inhabitants.Footnote 1

Figure 1. The courtyard of the palace at the beginning of the twentieth century. Postcard, author's private collection.

This article will outline a social profile of the evicted people that reaches beyond the stigmatizing labels provided by the institutional correspondence and the press. I will briefly retrace the story of the palace, and its transient population, and describe the tenants on the eve of the first expulsions in 1921. Moreover, I will consider the problems caused by a building being designated as a heritage site while it was still inhabited by a number of families, in the specific and delicate circumstances of the Italian post-war period, in order to explore the non-linear process of the expulsions. This article is part of ongoing research that encompasses the material history of the building, the social history of its owners and tenants and the political and cultural history of heritage. It is part of the urban historical genre of the ‘biography of a building’.Footnote 2 Studying a palace assumes the individuality of the building as a starting point for research, on a scale located between the substantial spaces of the city, districts and streets, and the history of houses and flats. This scale, generally ignored, invites a comparison among sources on the history of a building, from the stones themselves to representations, the social subjects and the institutions, without excluding the actual residents from analysis.Footnote 3 The ‘biography of a building’ allows for the inscription in space of specific forms of popular living and the mobilization, in line with the nominative technique, of quantitative approaches to the ensemble of tenants with qualitative approaches to individuals and families. Writing the biography of a building offers a way of applying microhistory to a particular urban space, whilst revealing the complexities of the wider urban experience through a close reading of the lives of its residents as well as the relationship between a building and its surrounding area.Footnote 4

Palazzo Costabili: from aristocratic residence to lower-class tenement

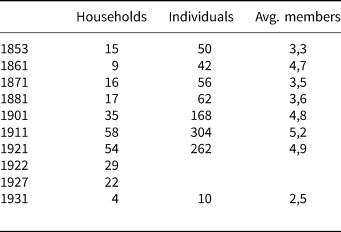

Palazzo Costabili, the Renaissance architectural jewel of Ferrara, was designed by Biagio Rossetti and built in the first years of the sixteenth century. It was erected in Via della Ghiara, a street in the so-called ‘addition of Borso’ that had connected the walled city with an island in the Po river, site of the monastery of St Anthony (Figure 2), during the fifteenth century. The noble house of the Costabilis, and later the Bevilacquas, was divided at the end of the seventeenth century between the families of the Earls Scroffa and the Marquises Calcagnini.Footnote 5 The palace was significantly transformed during the nineteenth century. It changed from being an aristocratic house: the Calcagninis, owners of the western side, had stopped living there by the mid-sixteenth century, renting the less prestigious apartments to humbler households. In 1809, after an auction for debts, the Scroffas were evicted from the eastern side, which was acquired by the bourgeois Bartolomeo Bertoni, whose family resided there until the 1840s, subsequently leaving the property to be split up.Footnote 6 The vast outdoor space encompassed a vegetable garden with trees; the buildings in the courtyard of honour were assigned to a market gardener and, from the 1830s, to a butcher and a shopkeeper.Footnote 7 In 1855, Jacob Burckhardt celebrated the palace in his Cicerone (‘it is worth a hundred palaces’), while acknowledging the risk that it could ‘fall into ruin’.Footnote 8 The events of the Risorgimento left their mark on the palace. In 1860, despite the protests of the owners, the army occupied the building, displaced some of the residents and transformed several spaces into a bakery for the ‘subsistence’ of the troops, with large warehouses for grain and wheat. For this reason, it was thereafter popularly called palazzone della sussistenza. Footnote 9 The palace remained nearly empty during the following decades, except for the presence on the noble floor of the Roman Earl Francesco Ferretti, the Austrian-Hungarian consul in Ferrara. Only the less valued parts of the building were occupied by people such as market gardeners, servants, artisans, potboys, labourers and day workers, as well as by small retailers (these included the managers of internal activities, including a bakery and a coal depot), a municipal guard and a piano repairman. A few important frescos attributed to Garofalo located in the rooms on the ground floor drew the attention of the authority responsible for the protection of monuments, which resisted the recurrent temptations of the owners to remove the paintings and sell them, a situation that was brought to court in 1889. In general, the authority was concerned with the stability of the palace, which was clearly poorly maintained.Footnote 10 Although the state of the building went unreported by the authorities, the palace could not offer anything but the poorest living conditions to its tenants: it had no regular heating or kitchens inside the apartments, the running water and lavatories were located outside the building, while refuse sometimes accumulated in the courtyard, visible from the street.Footnote 11 At the end of the century, a significant change took place (Table 1). Since Calcagnini had no direct heirs, his wing of the palace went to Marquis Antinori of Florence, who continued to let the apartments to working-class tenants. The other portion, formerly belonging to the Bertonis, had been inherited in part by the Beltrame family, who entirely renovated it before selling it to Giovanni Giovannini, a chemist from Porotto, a rural village situated about 10 kilometres west of the city. The new owner immediately tried to maximize the income he could extract from the building by increasing the number of tenants through the division of the flats, including the best ones, embellished with decorated marbles and plasters, frescos and vaulted ceilings. In this way, the number of registered inhabitants, 62 in 1881, had doubled 20 years later (168 in 1901), and in 1911 had increased nearly fivefold (to 304). The presence of such a mass of people provoked concern for the future of the palace; from then on, the ‘problem’ of the tenants was given constant attention by the public authorities. Local public opinion was concerned with other kinds of danger, including their own personal safety – for example, when the ‘Spanish flu’ arrived in Ferrara at the end of 1918, Palazzo Costabili was explicitly considered to be a crowded area at risk of infection. In 1919, a young man living in the palazzone, already convicted for theft and repeated desertion during the war, was arrested in a bar nearby after trying to escape by breaking the main window; in 1921, a knife-fight between tenants broke out just outside the main entrance.Footnote 12 The story of the palazzone shows how an increased population settled in the buildings of old Ferrara, a phenomenon that remains worthy of investigation.Footnote 13 The city was not involved in industrial development, except for the great sugar factories (which provided seasonal employment) and a number of small and medium workshops devoted to traditional industries. Ferrara continued to service the flourishing agriculture of the province and the residences of the local ruling class. The slow but continual demographic increase was driven, in the classic way of European urbanization, by the immigration of peasants attracted by job opportunities, for example in domestic service or on construction sites as urban modernization projects multiplied.Footnote 14 Characterized by large green zones within the city walls, Ferrara, like other nineteenth-century small and medium-sized European cities, was relatively untouched by the industrial revolution. As a result, it did not expand either inside or outside its historical perimeter, with the exception of the former military parade-ground (which was significantly renamed the ‘garden district’) and the popular and semi-rural suburbs along the river (San Luca, San Giorgio and Quacchio). Until the ‘housing crisis’ of the post-World War I period, which represented a breaking point but did not invert the dynamics described,Footnote 15 demographic growth only stimulated a few new constructions. These mainly involved the conversion of existing buildings, including historical palaces, former monasteries and dilapidated old houses.

Figure 2. The palace (no. 130) in Andrea Bolzoni's ‘Pianta e alzato della città di Ferrara’, 1747. Courtesy Biblioteca comunale Ariostea, Ferrara.

Table 1. Population of Palazzo Costabili (1853–1931)

Sources: ASCFe, Ruolo 1860, sch. 361–1 and pp. 567–8 of the registry; Registro di popolazione, Città, 12, pp. 3003–5, and 15, pp. 4741–5; Censimento 1871, Città, Sez. 5, sch. 270–9 and 323–7; Censimento 1881, Corso Ghiara, sch. 128–42, and Via Porta d'Amore, sch. 185–6; Censimento 1901, Frazione 1A, Sez. 19, pp. 280–303, 507–14, 816–17 and 830; Censimento 1911, Sez. A20, sch. 420–67 and Sez. A21, sch. 139–48; Censimento 1921, Sez. A26, sch. 53–65 and Sez. A27, sch. 73–113 and 244; Censimento 1931, Ferrara, Sez. A18, sch. 198, 844 and 852; ASFe, Prefettura-Gabinetto 1918–1954, b. 25, f. 998: lists Inquilini della parte…di proprietà Antinori and Inquilini…nell'ex proprietà Giovannini, attached to the handwritten minutes of the meeting held on 19 Apr. 1921; SABAP, b. N5–2164, list Inquilini del Palazzo di Ludovico il Moro attached to Ispettore to Soprintendente, Ferrara, 4 Apr. 1921; b. X5–2224, list of tenants attached to Intendente to Soprintendente, Ferrara, 27 Oct. 1927.

Origins of tenants, turnover in the palace and migratory geographies

The census figures confirm the role of Palazzo Costabili as one of the destinations of immigrants to Ferrara.Footnote 16 The census of 1921 asked for the county in which people were born rather than their town or village. This fact blurs the crucial distinction between the walled city and the forese (the large county territory outside the city walls – over 400 square kilometres), and makes it impossible to calculate migration accurately from the nearby countryside. However, 22 of the 189 people born in the city county (72 per cent of the total housed in the palace) had indicated their place of birth as forese villages, an error that illustrates the importance of the phenomenon. There were 59 people from the wider province (23 per cent of the total, mainly from the densely populated neighbouring counties of Copparo and Portomaggiore), whereas only 14 came from other provinces (5 per cent, primarily from the Veneto and Bologna). By merging the counties of birth of all members of each household, it is possible to identify different typologies. There are two categories that occur most frequently: one that combines births in the city county and in the province, which illustrates the extent of geographical mobility and of inter-county marriages (24 households for 125 people); and one that consists of people born in the wider county of Ferrara (18 households for 92 people), hinting at a stricter mobility. This factor, however, must not be interpreted as a kind of urban endogamy, since seven of these latter households included people born in the forese, a figure produced by a misinterpretation of the census question and, therefore, surely underestimated.Footnote 17 A person born in the municipality could be in a family of both types, whereas it is more likely that a person from the province would be in a ‘mixed’ family along with natives of the municipality. In the mixed groups, there were 15 municipal natives with a provincial relative, a figure that shows the importance of the bonds between women immigrants and men resident in the city (and occasionally male immigrants and women residents); less frequent (6 cases) were the all-provincial couples who probably immigrated together and at least some of whose children were born in the city. In the absence of migration data and without permission to access directly the twentieth-century register (anagrafe), we do not know when these rural people entered the city and when they were installed in the palazzone; nor can we reconstruct their residential patterns or their potential rural–urban circulation. Nonetheless, some census comparisons and a survey of the nineteenth-century register can offer valuable points for analysis.

A comparison with the previous census reveals a high turnover rate. Only 56 of the 304 inhabitants in 1911 still lived in the palace 10 years later (18 per cent); taking into account the decrease in the number of tenants, these represented 21 per cent of the inhabitants in 1921, or 28 per cent after deducting children – those born after 1910. There is an impression of a greater volatility compared with the previous inter-census period (1901–11): only 15 of the 168 inhabitants in 1901 (9 per cent) were still present 10 years later, when they represented a mere 5 per cent of a population that had nearly doubled – or 7 per cent after deducting those born after 1900. From the partial viewpoint of a popular tenement, the war and the post-war periods seem to have stabilized residential mobility to some extent. However, if we compare the inter-census range of a long 20-year period (1881–1901), we find that 21 inhabitants in 1881 (34 per cent) were still in the palace in 1901: in an increasing population they represented only 13 per cent of the inhabitants in 1901, but 27 per cent after deduction from the total number of people born after 1880. Therefore, over a longer period of time, the turnover of the first years of the twentieth century is the real change when compared with the greater stability of the late nineteenth century and 1910s. These figures must not be overestimated. The reason may have been a simple matter of space: at the end of the nineteenth century, in order to attract more tenants, the new owners opened new houses and used existing ones in a different way, without evicting the previous inhabitants; but, in the early twentieth century, the increasing inflow to Ferrara produced a marked turnover, subsequently slowed by the war.

None of the people listed in 1921 were present at the 1901 census. In the private list of Antinori's tenants compiled in 1920, one elderly resident was recorded. Luigi Sandri was a mason and was also listed in the palazzone in 1901 and 1911 as the eldest son of an unmarried couple, a carpenter and a housekeeper born in the city. Sandri's parents had lived in Stellata in the municipality of Bondeno on the river Po, where in 1885 Luigi was born and grew up. The places of birth of Luigi's brothers allow us to determine that his parents returned to the city between 1892 and 1897. Another case indicates the shifting patterns of residence of a couple from the forese. Albina Carlini, a housekeeper born in Monestirolo in 1854 or 1855, married Luigi Lombardi, a rural labourer (Quacchio, 1853), in 1890. She appears in the 1901 census list with her husband and two children, but not in the census of 1911, when they lived somewhere else. Carlini is, however, present on the 1921 list, as a widow with only one son registered – Ferdinando, a mechanic born in Ferrara in 1891 – who was absent, since he had been admitted to the nearby mental hospital. Her husband Luigi had still been included in Antinori's list of 1920 as a market gardener at the palace, so his death must have been recent.

The nineteenth-century population registers, the first of Ferrara's anagrafe, tell us something about the older generation of tenants. Luigi Lombardi was the son of Carlo and Claudia, who were born in different districts of Portomaggiore between 1819 and 1822 (see Figure 3 for a map of named places). Their trajectory before Ferrara's inclusion in the new Italian kingdom, probably determined by job opportunities for Carlo, who was classified simply as ‘labourer’ at the age of 40, can be approximately retraced from the birthplaces of their sons. The young couple moved to the semi-rural suburbs of Ferrara (San Giorgio, 1843), then to Copparo county (Fossalta, 1848), and later to the suburb of Quacchio in 1850. As a child, Luigi, born in 1853, moved often within the rural forese: two sisters were born at Fossanova San Marco (in 1858 and 1862), where the family was inscribed in the registry in 1861. The Lombardis moved to another forese village, Aguscello in 1865, and returned to Portomaggiore in 1869, where they became grandparents in their fifties. They soon went back to the forese (Focomorto, in 1871), from whence they moved again to the municipality of Copparo (Tamara, in 1872), where they qualified as boari, one step above labourer, as a result of an agricultural contract typical of Ferrara, which provided a monthly wage and a share of the annual crops. Luigi had moved five times by the time he reached his twenties and always to different places; following his family, he moved to Pontelagoscuro, then to Cassana in the north-western sector of the county, diametrically opposite to his previous residence. Luigi's mother died in 1877 in Cassana and the next year he moved to Gaibanella, back to the south-eastern sector of the county, where his father died, like his mother, before the age of 60. At the age of 23, as the eldest child, Luigi was the head of the household while the family moved to San Egidio in 1884 and Gaibanella in 1885.

Figure 3. Residences of Lombardi family members.

It was probably owing to his sister Maria, who was qualified as a housemaid, that the two moved inside Ferrara's walls for the first time in 1886, to Corso Giovecca, one of the city's main streets. Their orphan nephew Arturo joined them in 1888, but the following year Luigi and his brother Enrico moved again to Copparo county (Gradizza), and in 1890 Luigi returned to the city alone. At first, he joined his sister in Via Madama; then he married Albina and took up residence in another house in Corso Giovecca, where his first child Ferdinando was born. In 1891, the family moved to Via Pioppa, in the less-built-up part of the city, where Luigi started his career as a market gardener, which allowed him relative residential stability. Arturo and the other nephew Antonio joined them in that house. Another child was born (Adolfo, called Rodolfo, in 1892). The sons went to school, as their mother had done, unlike Luigi, who was illiterate. In 1900, they moved to Palazzo Costabili, together with Luigi's brother Enrico, who finally came back from Copparo. In less than half a century, Luigi had changed address at least 16 times, but his mobility did not stop: in 1911, he was not in the census list of the palazzone, but returned later, and he died there between 1920 and 1921. Albina too died there in 1928.Footnote 18 Luigi's parents, born in the countryside, moved closer to the city: they lived in the suburbs, in the rural districts of the forese and in other villages away from Ferrara. According to available sources, their children passed through different places (Figure 4): the first-born (Cesare) died young after having moved around, like his parents, without entering the city; the eldest daughter (Rosa) appears to have done the same; Luigi and Maria, however, arrived in Ferrara and at the end, although they moved inside and outside the old walls, they remained in the city, like the eldest grandchildren of Carlo and Claudia (Arturo and Antonio, Cesare's children); their other brothers, Enrico and Augusto, also came to the city from Copparo county. The turning point in the choice between rural and urban settlements seems to have been the sequence of deaths from 1877 to 1880 (Figure 5): while the households of the parents and of the eldest son were dissolved, the second-born Enrico lived not far from the Duomo and one of the orphans, Antonio, settled in Via Cortebella, a peripheral zone next to Piazza d'Armi.

Figure 4. Residence areas of the members of the Lombardi family (according to their age).

Figure 5. Residence areas of the members of the Lombardi family (according to calendar year).

What do these fragments of trajectories teach us? First, they confirm the high degree of mobility of Ferrara's rural population. Different forms of mobility existed there, which were reversible, rather than reducible to linear paths.Footnote 19 This shows how smaller cities like Ferrara were just as much the pivot of a complex texture of migrations as were larger industrial cities.Footnote 20 While it is difficult to assess the significance of neighbourhood networks, place of work or solidarity among fellow countrymen, relatives were one impetus for this mobility, both for the movements of minors with their families of birth or aggregation (like the uncles' families), and for the siblings who settled in different parts of the county.

Who were the last tenants? Young people and the working poor

The census forms of 1921 allow us to retrace the profile of the people who lived in the palace just before the start of the eviction. Previously, the administrative correspondence between bureaucracies had estimated that there were 40–50 families in the palace. It is not clear why the authorities did not consult the local registry office, which in the first years of the twentieth century was modernized (loose family forms instead of bound registers). Maybe it was an awareness of the persistent importance of non-registered mobility that made a direct approach more advisable, with the authorities first asking for lists of tenants from the old owners, then conferring on the inspector of monuments the duty of compiling a revised list.

The census of 1921 registered 54 households in the palace, more than were detected in the quoted private lists (48 and 42), but congruent with the data from the previous census (58). Family forms reported 262 inhabitants, 40 fewer than in 1911. There was substantial gender equality, but the average number of family members had slightly decreased (from 5.2 to 4.9), although the figure covers disparate distribution, from solitary households to those containing 12 people.

The calculation of rates of overcrowding can only give an approximate idea of the effective saturation of spaces, since the (unknown) surface area varied from the small rooms in the mezzanine to the huge rooms in the best apartments. The average was 3.3 residents per room, in a range of situations: one couple had three rooms, but cases of two or three people per room were more frequent (25), while a consistent number was over that threshold, with 5 people per room (15) or more (7), and one extreme situation where 11 people lived in one space.

The family typology is also composite. According to Peter Laslett's typology, we can observe the prevalence of nuclear families, even if we take into account all registered people, including temporary presences or absences, married and non-married couples.Footnote 21 There were 33 couples with or without children, including one-parent households as a result of widowhood or separation. There were 18 complex families: only four of these were multiple families with more than one couple formed by the children or siblings of the main couple; the remaining 14 cases were extended families, with additional members like non-family babies (wet nurse), nephews, orphans, grandchildren, parents, sisters, cousins and other cohabitants. The picture is completed by the two single individuals and a group of orphan brothers in the custody of the eldest. The heads of household were in the same age range; therefore it seems that the family lifecycle had no influence on family type.

The age pyramid shows a young population. At the extremes, we find nine children under one year old and one widow aged 78 (born in the province in 1843). Half of the inhabitants were under 21, whereas the most numerous age ranges were 11–20 and 0–10. Only one fifth were older than 40. The data is confirmed by the calculation of the relationships of the members to the respective head of the family: of the 123 registered, slightly less than a half were sons or daughters.

As far as professions were concerned, the criteria of the 1921 census, which splits the sector and the position in the productive process, allows for an in-depth analysis. There were 185 people with registered professions and they broadly coincide with the population over 12 years old. Simplifying the approach, it is possible to distinguish several groups. There are 42 housekeepers – 58 if we consider people without an indicated profession who answered the question on ‘condition’ by stating they were ‘attending to home’. There were 14 students or pupils, but 17 if we consider the answers to other census questions. The profiles of the remaining 129 people were distributed across several positions that we can sum up as unskilled worker (102): dependent workers, female and male, such as labourers or day-labourers in industry or handicraft, or employed in a small way in the service industry or agriculture. There was also a small nucleus of civil servants (7). There was a foreman (mechanic), one employee and one salesman. The independent workers were a grocer, with the shop in the palace, and a market gardener, who cultivated the inner garden. There is some doubt about the status both of a cattle dealer and a 69-year-old unemployed midwife. There were also two peddlers, who belonged to the underclass. Despite proximity with urban social marginality, reinforced by the overcrowded conditions and the rudimentary services in the palace, most of the adult population was ‘active’ and the great majority were employed in subordinated waged positions in industrial and handicraft activities. The palazzone, then, was full of children and young people, who belonged mostly to families of the working poor.

The problem of an inhabited heritage

In 1920, the authorities decided that the palace's new situation as a monument owned by the state and occupied by former tenants would be reversed by the eviction of the inhabitants.Footnote 22 Their presence was perceived not only as an objective threat to the building, for which the owners were in part responsible, but as a subjective act against the palace, regarded as ‘vandalism’ and ‘barbarity’. Among the many examples of a pervasive rhetoric of contempt, the palace was named a ‘filthy refuge of Victor Hugo-like beggars’ or, in the same vein, ‘a Court of Miracles’.Footnote 23 The move to ‘clear’ the palace was publicly declared to be urgent; it was at the centre of a press campaign and of institutional correspondence, but it remained unrealized for a long time, for many reasons.

First and foremost, between the purchase contract (January 1920) and the effective acquisition by the state (January 1922), two years were needed to collect the money in order to pay the previous owners. The stalemate, worsened by inner bureaucratic conflicts and the change of personnel,Footnote 24 contributed to convincing the tenants that uncertainty offered an opportunity to avoid payment of rent.

Secondly, after the war Italy had maintained the rigid housing norms effective during the conflict, which imposed a ban on evictions and rent increases, as in other European states.Footnote 25 There was a governmental commissioner for housing in Ferrara also, who had to resolve problems linked with the need for housing, which worsened at the end of the war.Footnote 26 Awareness of this situation confirmed to the population of Palazzo Costabili that it was possible to avoid or at least delay the eviction.

The juridical framework did not prevent the eviction of the tenants, as long as other cheap accommodation was provided. But the housing problem that had caused overcrowding at the palace for years impeded the finding of alternative residential places. The authorities’ efforts to obtain homes for hundreds of people were fruitless.Footnote 27 The solution proposed in December 1920, with the ‘restitution’ of Mortara barracks to the municipality, required a considerable amount of work to adapt the premises to living areas. These started after complicated discussions on the division of expenses in June 1921 and lasted until the end of the year.Footnote 28 In this case, the tenants played a role, since during the summer the households which had to move refused to do so, judging the new accommodation unsuitable to live in: it consisted of a simple partition of the vast dormitory into small apartments without a roof. The press talked about it, and the prefect and the new commissioner for housing agreed with the tenants.Footnote 29 Other work was then necessary in order to proceed with the eviction.

Finally, expelling people without providing suitable lodging would have sharpened social conflicts in Ferrara, where there were already high political tensions because of the rural squadrismo and recurrent fights between fascists and socialists.Footnote 30 Palazzo Costabili and the area around it was involved in some of these struggles. For example, in July 1921, a fascist squad invaded the palace in response to alleged incitements by the tenants during a fight between the fascists and the leftist arditi del popolo in a nearby bar. At the end of the year, a fascist who lived in the palace was shot, but the anarchist who was charged was acquitted. Until 1929, the words ‘Viva Lenin’ were engraved on a column in the courtyard of honour. The city's podestà (the fascist mayor) was personally involved in its removal.Footnote 31

The first partial expulsion was unwittingly promoted by the inhabitants, who gave the authorities a reason to intervene. In the summer of 1920, the local press spread the rumour that if the inhabitants of the palace were evicted they would burn it down. Later, the same plan was attributed to the ‘several Red Guards’ staying in the palace. It is not possible to confirm the truth of the threat, but it could have been a challenge, rather than a plan.Footnote 32 It is true that the tenants allowed their children to throw stones at passers-by or at the chapiters of the honour courtyard, and sometimes the young demolished the inner walls, but it was not easy to keep them under control. Neighbourhood children also frequented the palace, and their behaviour was affected by family difficulties in the war context, as newspapers reported.Footnote 33 If the adults wanted to vandalize the palace, it would have been easy, but the Renaissance frescos were never intentionally damaged. Some were ruined, but as a result of the negligence of the state or the owners. More prosaically, tenants were aware that they would have to leave their homes one day, and this precariousness added to the already difficult living conditions in the palace. Moreover, as the former owners neglected the palace, its doors, windows and roofs were gradually removed by inhabitants. Despite the authorities’ perception of this behaviour as ‘vandalism’, it is more likely that it was a survival strategy; the materials could be sold to building enterprises or antique dealers, or could simply be used to light the fire in the kitchens to avoid spending money on wood or coal. At the same time, more policemen, carabinieri and royal guards were asked to control the palace, but the request could not be satisfied because of the difficulties controlling public security more widely in Ferrara. Finally, it was impossible to proceed with a trial since the real or presumed culprits were not easy to identify.Footnote 34

In March 1921, Arturo Giglioli, the inspector for monuments, wrote to the supervisor for the protection of monuments Ambrogio Annoni: ‘After the removal of the truss, the roof has suffered and the security is threatened. Exaggerating the fact, we could declare it precarious in order to push the local authority to expel all the tenants.’ The superintendent informed the prefect, who alerted the public works office, which ordered an inspection. The inspection confirmed that the roof was in a ‘dangerous static condition’, because of the recent ‘devastation’, the ‘natural deterioration’ of time and the ‘irrational construction system applied’. In those days, Giglioli and the master builder Vittorio Ungarelli visited the palace for another ‘accurate inspection of the roof, which is in a really catastrophic and unstable condition’. The refurbishment of the roof was decided on.Footnote 35 The town commissioner, Alberto Cian, sent a municipal engineer, who confirmed the risks. On 19 April, a meeting took place and it was decided that the commissioner would issue a decree of expulsion and reparation (art. 153 of the municipal law, Consolidated Act 1915); at the same time, the commissioner for housing would confiscate Mortara to house the evicted.Footnote 36 The process would be carried out at the end of the year, after the refurbishment.

The progress of the expulsions

On 9 December 1921, a few days after the census operation, the superintendent telegraphed his predecessor triumphantly announcing: ‘Today we are going to expel the tenants of the main entrance’. The minister Giovanni Rosadi, who visited Ferrara a few days later, had publicly announced the solution in an answer to a parliamentary question on the palace. At this point, the palace could officially become a national property (25 January 1922), even if the situation was still contentious. The superintendent informed the ministry about ‘several attempts to return to their houses’ by evicted tenants, including threatening the guardian.Footnote 37 It is not easy to distinguish who was expelled and when: the local inspector wanted to add another two households to the group of the evicted; therefore, the superintendent counted 20 families that were moved.Footnote 38 Cross-referencing the data (the census data, the lists of tenants produced in 1922–23 and the registry family forms), the resulting figure is quite reliable.Footnote 39 Despite the wishes of the authorities, the remaining families, lodged in the wing of the palace along Via Porta d'Amore and in the south-eastern side of the building (the cadastral unit numbered 5078 in Figure 6), both of which had separate access, were not touched by the second wave of expulsions. During this period, someone applied for an apartment in the palace, but new tenants would have caused a ‘real uprising’ and ‘danger to the safety of the palace’, as Giglioli said. The guardian asked to be able to carry a gun to protect himself.Footnote 40 Despite the fact that the new superintendent, Luigi Corsini, wanted the ‘eviction’ in order to have ‘complete availability of all the building’, the situation became stable.Footnote 41 There were several ideas about how to use the palace, but refurbishment was delayed due to more collapses and destruction.Footnote 42 In May 1926, the local commission for housing and the fascist party federation decided to suspend the evictions in Ferrara; they also arranged for the palazzone's ‘abusive’ inhabitants (those in the south-eastern side) to regularize their position, paying a rent to the state. The local press pointed out the recurrent invasions of men and couples in the rooms and in the courtyards of the building, but the new list of tenants, drafted in 1927, included 22 families still occupying the same flats they were living in five years earlier.Footnote 43 With a few exceptions, the palace's remaining population was expelled in March 1929.Footnote 44 At the beginning of 1930, the local office of the Ministry of Finance declared that the only people remaining in the building were two guardians, one female tenant and a non-resident artist, who placed his studio in the palace.Footnote 45 In the census of 1931, there was just one female tenant, the guardian's wife, a family registered as having migrated to South America and another guardian who cultivated the garden.Footnote 46

Figure 6. Cadastral map of the palace, 1922. Courtesy of Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio, Ravenna.

Since 1929, the state had considered designating the palace as a home for the precious archaeological collection that had emerged from the reclamation of Comacchio's swamps. The refurbishment and establishment would have to wait until 1932, when one million lire of funding enabled the works to start. The sum was personally diverted by Mussolini from the funding for public works to mitigate unemployment, probably after pressure from Ferrara's powerful representatives, especially Italo Balbo. Ferrara was one of the cultural capital cities of Italian fascism, with a relative degree of autonomy from central policies, including in political uses of the past. While the main topics of the regime were ancient Rome and the modern Risorgimento, linked together in order to glorify national (and fascist) identity, the celebration of the local past focused on other periods and genealogies: pre-Roman Etruscans, the early Middle Ages (the birth of Ferrara) and especially the Renaissance (the golden age of the city, capital of the Este Duchy).Footnote 47 The museum was inaugurated on Sunday, 20 October 1935, in the presence of authorities and with much attention from the national press. When the celebrations concluded late in the evening, one of the restorers had a suit, a gold watch and other personal effects stolen from his room under the roof. Whoever entered the room knew the spaces and, more importantly, where the director's dwelling was, but thieves could not have got in. Given the absence of any other clues, we can suppose that the theft was carried out or directed by ex-tenants, who may have hoped to take advantage of the palace for the last time.Footnote 48

Conclusion

The analysis of a particular case of interaction between the heritage-making of a historical palace and the destiny of its residents has confirmed some crucial points underlined by recent urban historiography. The interplay between social factors (new owners, who put inside new poor tenants) and material factors (further physical deterioration of the building itself) contributed to the beginning of the eviction of the palace's occupants. A central question is also the role of the owners: first, the bourgeois who wanted to capitalize on the property by filling it with people; then nationalization, which sees the intervention of different bureaucracies whose members do not always agree. Demographic analysis shows that the social profile of tenants did not correspond to the image of a marginalized and uprooted population, but to the most mobile working poor. In a conjuncture of high levels of mobilization (returning from the war, class conflicts, the fight against rising prices and the housing crisis) and of fights among social and political groups (fascist squad violence and socialists’ and workers’ responses), the inhabitants resisted the evictions and their agency conditioned their own destiny, although in paradoxical forms. Ferrara's specific demographic and building dynamics and its reduced residential alternatives inside the old city walls must also be considered, along with the local social and political context. Nonetheless, the ‘biography of a building’ perspective offers the opportunity to bring together different stages and sources of urban history, starting from a demographic analysis that includes mobility. Regarding the palace as an analytical subject to be interrogated in an intensive but not isolated way can solicit a new examination of some fundamental questions. In the Italian conjuncture of the 1920s (between the end of the liberal state and the advent of fascism), it offers a new reading of the post-war housing crisis, the conflict between heritage protection and the life of the population and the issues of housing policy. More generally, this approach helps us to reconsider the problems caused by heritage-making, the significant presence of children and teenagers in urban societies, the residential careers of immigrants from the countryside, the social networks of the working poor and the agency of subaltern classes.