An addendum to my earlier post, to explain more directly why I am skeptical of the argument that public choice is a useful lens to understand the politics of the public during coronavirus. Shorter version: if the “public” is indeed some kind of equilibrium, then the underlying game is unlikely to be the kind of game that public choice scholars like to model.

As best as I can tell, the “public” that public choice scholars are talking about is an equilibrium in some underlying game, the nature of which isn’t fully specified anywhere that I’ve seen (perhaps I’ve missed it; or I’m looking in the wrong places). The argument seems to be that the ‘stay at home until things get safer’ equilibrium is fragile, or perhaps non-existent, and destined to be overwhelmed when everyone opts for ‘get back into the real economy.’

It may be that this prediction turns out to be empirically right. But the question for me is not what the equilibrium is, but what the underlying game is. When someone tells me to “solve for the equilibrium” (as if it is obvious to someone with a minimal understanding of economics), I am usually more interested in (a) solving for the model that they presume is self-evident, and (b) trying to solve for the question of whether there are other models, which may tell us different things or capture better the logic of what is happening. This is especially pertinent here, because the public choice approach tends to prefer models that I suspect are particularly unlikely to be helpful in understanding key aspects of the public’s reactions to coronavirus.

Why is public choice specifically unhelpful here? Rather than starting from the many definitions of public choice offered by its enemies, I’ll begin with the definition provided by one of its major proponents. As described by the late Charles Rowley, longtime editor of the journal Public Choice, the public choice approach is a ““program of scientific endeavor that exposed government failure coupled to a programme of moral philosophy that supported constitutional reform designed to limit government.” In other words, it is not a neutral research program, but one that has a clear political philosophy and set of aims. Bluntly put, it starts from governments bad, markets good, and further assumes that the intersection between governments and markets (where private interests are able to “capture” government) is very bad indeed.

This is useful for understanding some aspects of politics. It turns out that government officials can indeed be self-interested, and that government programs can be captured by their constituents. There is there is some intellectual crossover between public choice and e.g. Theda Skocpol style historical institutionalist accounts of government agency-client relations, even though they have very different valences. Furthermore, the fact that public choice has an associated political program doesn’t mean that it is necessarily bad. There is an interesting affinity between public choice and Marxism, another analytic approach with an associated political program. Both agree on the awful things that can happen when government and business interests are in cahoots, even if each sees a different party as the serpent in its paradise.

However, it does mean that there are some questions that it is going to be systematically weak in addressing. In particular, public choice notoriously tends to define questions of private power out of existence, treating them as freely entered contracts that hence reflect the interests of the contractees. This is why Mancur Olson accused his public choice colleagues of “monodiabolism” and an “almost utopian lack of concern about other problems” than the unrestrained state. Public choice economists tend to wave away private power as being irrelevant to the understanding of outcomes, except when it acquires the additional force of state coercion.

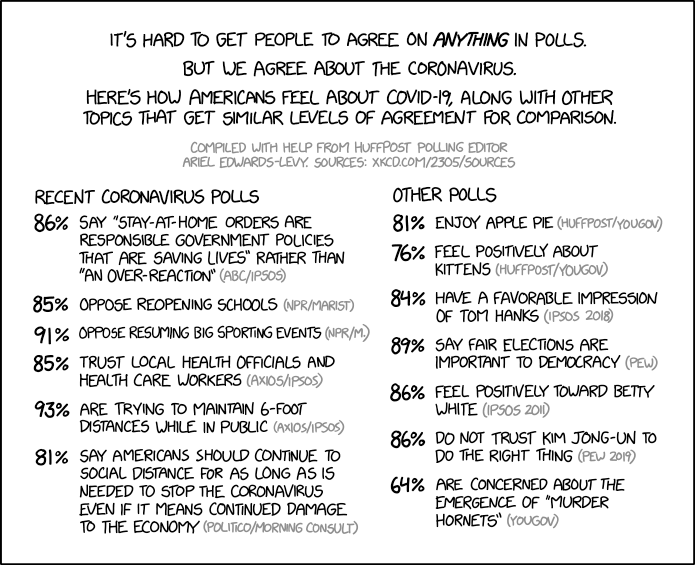

And this is why it’s a terrible starting point for understanding the public response to coronavirus. As the XKCD cartoon above shows, the evidence from public opinion polling is emphatic. People – with the exception of a small minority – are in favor of stay at home orders, and closed schools and non-essential businesses. It could be that people are lying to the pollsters because of social acceptability bias – but it would be unprecedented for so many of them to be lying. I haven’t seen any public choice people confront this evidence head on – instead, they try to move the conversation to other forms of evidence (movement data from phone companies) that is more ambiguous and arguably more congenial to their arguments. This is not a particularly convincing rejoinder. If there is an instance of democratically legitimate coercion, then stay at home orders are it. Presumably, people don’t want to stay at home forever – but a very large majority of them don’t believe that it’s safe to go out, and they strongly approve of government obliging people to stay indoors minimizing the risk.

So why then, may the equilibrium break down? It’s clearly not because of express demand from the public. Nor because of cheating (some people may want to free ride, even when the potential rewards include getting sick and dying, but it’s hard to see how they are a majority, or can create one).

The plausible answer is that private power asymmetries are playing a crucial role in undermining the equilibrium. Some people – employees with poor bargaining power and no savings – may find themselves effectively coerced into a return to work as normal.

Some illustrative evidence of how, if you’re not lucky, your employer’s power over you may very literally be the power of life and death.

Rafael Benjamin, 64, who worked at Cargill Inc.’s pork and beef processing plant in Hazleton, Pa., told his children on March 27 that a supervisor had instructed him to take off a face mask at work because it was causing unnecessary anxiety among other employees. On April 4, Benjamin called in sick with a cough and a fever before being taken to the hospital in an ambulance a few days later. He spent his 17th work anniversary at Cargill on a ventilator in the intensive care unit and died on April 19.

So why don’t you just demand safe working conditions? Perhaps you’re an undocumented immigrant who fears retaliation:

I go, and I come back, tested positive, I’ll give it to my children. And my whole family will be affected. So I’m really, really scared.

PAYNE: Like the other workers we spoke with, she fears retaliation. She says she worked shoulder to shoulder in the plant, which processes almost 20,000 hogs a day.

Or perhaps Trump has declared that your meatpacking plant must stay open as critical infrastructure and limited its legal liabilities.

Maybe then you should just quit your job? Perhaps not, if you want to be able to put food on the table:

As Ohio begins to ease restrictions and reopen its economy, the state is inviting employers to report employees who don’t show up for work out of concerns about the coronavirus for possible unemployment fraud. This means that workers who stay home because of concerns about unsafe conditions at work may be investigated and potentially stripped of unemployment benefits.

There is now a form on the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services website for employers to confidentially report employees “who quit or refuse work when it is available due to COVID-19,” flagging them for the state’s Office of Unemployment Insurance Operations

NB that this is certainly a situation where the state and private actors are looking to get into cahoots, but not in the ways that public choice economists have devoted significant analytic energy to. And if you want an illustration of Marxist arguments about the “structural power of capital” to threaten politicians through its investment decisions, you could hardly do better than Elon Musk’s efforts to force through the reopening of his factory against the law.

Where public choice people seem to perceive a “public” that collectively wants to return to work, I see something different – a set of asymmetric power relations that public choice scholars are systematically blind to in the ways that Chris, Alex Gourevitch and Corey identified eight years ago, when they wrote about “bleeding heart libertarians” (a constituency that strongly overlaps with public choice). It could of course be that I’m wrong. Perhaps indeed mobility data is a better indicator of people’s actual wants than what they say when they are asked by pollsters.

So here’s my bet. If the public choice analysis is right, and this is about some kind of broad and diffuse “public” pushing back against impossible regulations, then we will see a return to the economy sooner rather than later. But we can reasonably presume that this return will be roughly symmetric. People in general want to go back to work, they are voting with their feet to go back to work, and it’s just lefties and handwringing left-liberals who are oblivious to this.

In contrast, if I’m right, we will see a very different return to “normality.” The return to the economy will be sharply asymmetric. Those who are on the wrong end of private power relations – whether they are undocumented immigrants, or just the working poor – will return early and en masse. Those who have the choice and the bargaining power will tend instead to pick safety. They will be less likely to return to the workplace when they can work from home, they will go back later when they do go back, and when they do return to the workplace, they will make radical demands for changes that protect them.

You might object that this is an unfair bet, because it’s obvious that I’m picking the side that is going to win. That’s actually the point. Exactly because it is so obvious, it highlights the frequently brutal power relations that public choice scholars shove under the carpet when they talk about the “public” wanting an end to lockdown and a return to past economic relations. Intellectual programs that are designed from the ground up to assume government failure and private efficiency are terribly suited to understanding how many private relationships in fact work. There are places where public choice can be helpful in understanding aspects of the coronavirus response. Perhaps you might, e.g., apply it to the relationship between drug companies and regulators, and the ways in which intellectual property rules might hurt the search for a vaccine. That might or might not be helpful. But what is not helpful is its application as a theory of why “the public” is resisting a set of measures that the evidence suggests are actually highly popular with the public. Here, it’s more likely to mystify than to clarify.

{ 35 comments }

Brad DeLong 05.12.20 at 2:31 pm

I would note that Charles Rowley, in addition to being a leader of the hard ideological wing of public choice, was also completely barking mad—believed that we economists who disagree with him on the merits are pretty much all sinister and cynical apparatchiks whose true and fanatic allegiance is to I.V. Djugashvili. Viz:

Mike Huben 05.12.20 at 2:58 pm

A masterful and relevant takedown. This is why I read this blog.

Barry 05.12.20 at 3:37 pm

““program of scientific endeavor that exposed government failure coupled to a programme of moral philosophy that supported constitutional reform designed to limit government.†In other words, it is not a neutral research program, but one that has a clear political philosophy and set of aims. “”

In other words, it’s as ‘scientific’ as North Korean propaganda.

Lee A. Arnold 05.12.20 at 4:25 pm

Henry: “The plausible answer is that private power asymmetries are playing a crucial role in undermining the equilibrium.â€

I tried to express the same thing in my hastily-written comment under your other post, “Who is the ‘public’ in ‘public choice’?†Expressing it by way of a return question, who are the “elites†in the sentence: “The elites are now failingâ€? Consider economists and Republican party elites, and how far their “private power asymmetries” have progressed into the fabric of information:

Most economists, who have long considered themselves elite among the social scientists (and so far as I know, may still be salaried that way) have preached for the last 50 years that the market is the natural order, that government reduces economic growth, that government debt is bad, and that government money-creation must cause inflation. These falsehoods now rule the public debate. A major result is that it has been simply out-of-the-question to enact a temporary UBI until there is enough testing & tracing to restart the economy beyond its current necessities, and to leave it to central banks to monetize that debt and then apply the standard techniques of financial repression to prevent rapid inflation (although they’ve been doing a fair amount of exactly this since the middle of last year to bail out the financial repo market, long before coronavirus hit). In lieu of relief, why should it be any wonder that the public will feel “increasing pain, financially and psychologically,†as Hanson wrote at comment #24? And, is this not a great success by certain academic elites, in promulgating a bad message?

Or consider the success of Republican party elites, progessing well along in a coordinated three-pronged strategy to: 1. Demand reopening the economy (whether it is reopened or not) to counterargue against more relief spending (except bailouts of Senatorial portfolios in big finance, no doubt); 2. Predict higher death rates as the price we all must pay, to engage their supporters’ authoritarian callousness (so suck it up, you infirm snowflakes); and 3. Hide the real death toll and the new nursing home hot spots (as now reported in at least a few states controlled by Republicans) so that its emotional horror will be diffused in their supporters’ larger anger about “fake newsâ€.

Thus, some elites are far from failing in anything other than the intellectual sense. We ask again, which elites are presumed to be failing? Doctors, nurses, epidemiologists? In the present circumstance they might laugh at the suggestion they are elites to begin with. Which elites was Hanson writing about?

Marshall Steinbaum 05.12.20 at 4:40 pm

Re: Brad—

That’s a standard position in that crowd, I think. It’s certainly repeated ad infinitum (about Francis Amasa Walker, among others) in Thomas Leonard’s book Illiberal Reformers.

Boba 05.12.20 at 6:24 pm

Just want point out that the late Rafael Benjamin was doing his part to protect his coworkers, even if he or they didn’t know it. It is telling that the aesthetics and appearances seem to have higher value than expertise and sound practices.

nominal 05.12.20 at 6:25 pm

Is the problem with the “Public” or the “Choice” part of “Public Choice?” If a person is too poor to refuse to work, no reasonable person would say they are “choosing” to reenter the economy. They’d say they “have” to reenter the economy, i.e., they don’t have a choice.

bad Jim 05.13.20 at 5:43 am

Zeynep Tufekci has a heartwarming article in the Atlantic about how the citizens of Hong Kong crushed the curve:

With the government flailing, the city’s citizens decided to organize their own coronavirus response.

Z 05.13.20 at 8:01 am

The return to the economy will be sharply asymmetric. […] Those who have the choice and the bargaining power will tend instead to pick safety.

No need to speculate. Just as we were a couple of weeks ahead in terms of epidemic spread, France is this week beginning its reopening.

The dynamic you describe is clearly at play here, and opinion polls indicate a sharp divide between blue-collar, manual workers and popular classes (people who will loose the benefit of the exceptional unemployment benefits if they don’t go back to work, so who don’t have a choice but to go back) strongly in favor of continuing the lockdown, white-collar professionals (who are allowed and even encouraged not to come to their workplace, and who consequently won’t have to cram themselves in the suburb trains) significantly more in favor and the very rich and pro-business lobby actively campaigning for the reopening.

Tm 05.13.20 at 10:24 am

More data regarding elites (governors) vs the public:

https://www.vox.com/2020/5/12/21255768/poll-governors-reopen-popular-coronavirus-pandemic

“Many state governors have seen their popularity — and approval ratings — soar since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. But according to a new poll, how popular individual governors are seems to depend on how quickly they took steps to prevent the spread of the virus and whether they’ve thus far delayed reopening.“

It rarely if ever makes sense to talk about „the elites“ as if they were a single homogeneous entity. It is one thing when political activists resort to that kind of simplification for rhetorical effect, but when academic scholars talk like that, it should really raise alarm bells.

reason 05.13.20 at 12:38 pm

As a social democrat I have nothing at all against “constitutional reform designed to limit government”, however the devil is in the details. I certainly want President Donald Trump to have much less power.

I also think what would have been awfully helpful in the current circumstances is a three month pause (not stop pause) in mortgage payments and rents, and a temporary universal basic income coupled with a (moderate) tax increase. But rational policies are apparently off the table.

anonymous 05.13.20 at 4:37 pm

I think it is obvious that those for whom safety is least expensive, will choose the most safety, and those for whom safety is the most expensive, will opt for less safety. However I do not believe there is any conflict between upper class and lower class on coronavirus issues. For example, if you look at the polling behind that (cherry-picked and somewhat outdated) xkcd comic, you will see that lower income people generally are more in favor of reopening the economy. So it’s not a matter of rich people safely working from home and asking low-income workers to go back to work.

It seems to be your position that workers should be able to stay home indefinitely and have someone else pay for all of their needs, regardless of whether this is efficient (in the sense of the value workers place on the increased safety provided) or spectacularly inefficient. Meanwhile your position is that employers should be bankrupted and their employees laid off, because they should have no right to hire workers who want to work? It’s hard to see how these two positions are compatible in the long run. Unless you are an MMTer and believe there is a magical money machine so that nobody needs to work and yet somehow everyone can consume as much as they want.

I don’t think it is a surprise that most people would stay home, be safe, and get paid as much or more than before, if they could. But if an employer is permitted to open up and wants to open up to avoid bankruptcy, why should they not be able to hire someone to do so if they agree to it? Is the heart of your argument that giving someone a job they want gives you too much power over them and should not be allowed? What about a doctor who wants to give me life-saving medical care? Doesn’t that give them a lot of power over me? Should that be allowed? Or is there a difference between consent and non-consent, between voluntary actions and slavery?

Gar Lowe 05.13.20 at 5:23 pm

“The return to the economy will be sharply asymmetric. […] Those who have the choice and the bargaining power will tend instead to pick safety.”

Yep. I work in Silicon Valley and many large companies, including mine, have been telling us that we will likely work from home until the end of the year. The P.R. explanation is that we can work from home and keep the economy moving whereas people in retail, etc. must be physically at their jobs, so we should be the ones to help flatten the curve.

Fair enough, but my company said you could come to the office if you signed what is essentially a liability waiver. So, there are definitely liability concerns.

As for my small slice of the public (my colleagues), they are in broad agreement that we should still work from home for now.

Swami 05.13.20 at 5:41 pm

With all due respect for the author and all the comments so far, I think there is a major misunderstanding of what Public Choice is about. It has nothing to do in the slightest with the public’s preferred choice. It is about the economics of politics, and often specifically results in the public or the majority NOT getting its desired outcomes, due to vested interests, rent seeking, log rolling, minority focus and bureaucratic inertia.

I am not interested in trying to defend Public Choice theory, but this article either stems from or at least accentuates a previous misunderstanding of the issue.

anon/portly 05.13.20 at 6:00 pm

To me, and maybe I have this all wrong, the heart of “public choice” is something like “publicly elected officials want to be elected” and therefore the political process itself is a sort of market.

In the specific case of Hanson’s “the public speaks with one voice, and is deferring now, but will defer less over time” argument, I’d go the other way and say it isn’t Public Choice-y enough.

In this situation, you don’t even need the “re-election carrot” to motivate governors, you can use the “this is life or death, governors just want to do the right thing” argument. Part of “doing the right thing” effectively – I imagine they would believe – involves maintaining public support for your policies. Hanson’s suggestion that “elites” will insist on lockdown policies which the public will increasingly see as ineffective, in addition to resting perhaps too much on his own view that these policies are ineffective, also seems to rest on a view that the governors will not take public opinion into account.

In my state the first two things to be officially “reopened” by the governor were fishing and golf. Apparently the fishermen were complaining pretty loudly, and while perhaps this wasn’t taken into account, I don’t think it’s obvious that it would have been wrong for the governor to listen to them.

And with golf, I wonder if the fact that the state next door (a state with fewer deaths per million than, say, Norway) never banned golf played a role. Perhaps it didn’t, but I would think the governor might be wanting to avoid appearing inflexible and arbitrary, and a big part of that may be not ignoring what other states and countries are doing.

I think it is true that much of the social distancing, in every country (or almost every country), is voluntary, and ultimately under the control of the public, as a whole. Unlike Hanson, I think governors are going to be very conscious of the positive aspects of keeping public opinion on their side as much as possible, simply to make their policies as effective as possible.

Right now from a “Public Choice” perspective maybe the idea of the public pushing for opening and governors resisting may seem like the issue, but I wonder if it isn’t just as likely to go the opposite direction. For example, what about schools? What if the science seems to suggest opening elementary schools isn’t such a bad idea? What if public health experts tell the governor “come fall, taking 20 or 30 thousand 18-21 year olds out of the cities and isolating them for nine months in the middle of (various) nowhere(s) may actually save lives?” (I have no idea how likely this is, just throwing out a possibility). In such cases, it may be the governor pushing to “reopen,” not the people.

Henry 05.13.20 at 6:22 pm

Swami – I’ve co-edited a special issue of Public Choice and am reasonably familiar with the approach. The point that is being made in the title is that public choice scholars are actively making arguments about the “public” and what it wants – see the original post. This sits awkwardly with many elements of the public choice tradition (e.g. Riker’s skepticism about whether there is such a thing as a coherent democratic public; also the suggestion by Tyler Cowen on Twitter that governments that are relaxing the bans are appropriately responsive to public pressure), but I am not interested in engaging in an immanent critique and am happy to leave the internal incongruences to those interested in the internal debates. My point is simpler – that in situations where private power is crucial, public choice will be incapable of capturing the dynamics, and instead will resort to a kind of revealed preference argument in which behavior and outcome are imputed as evidence of what the “public” actually wants.

anon/portly 05.13.20 at 6:25 pm

In the specific case of the way undocumented workers (maybe also immigrant workers) are treated by firms, it’s hard for me to see why a public choice perspective is unhelpful. It seems to me that the way the government regulates immigration, and firms, and the way our political process is involved in these outcomes, is crucial to understanding that. You wouldn’t want to just ignore the government’s role, would you? It seems like the undocumented worker “equilibrium” in America is a very complex one.

MPAVictoria 05.13.20 at 6:47 pm

“because they should have no right to hire workers who want to work?”

The word “want” is doing an awful lot of work here anonymous…..

Swami 05.13.20 at 6:59 pm

Henry, thanks for the clarification.

As long as we agree that Public Choice is specifically (in part) an explanation of why the majority does not get what it wants or thinks it wants. Again, I have no desire to debate how well Public Choice performs in this capacity. My take on PC is that there are some interesting ideas and observations, but that the entire movement needed someone with a bit of marketing savvy and feel for nomenclature. “Rent seeking” is another term which actively does more to confuse the issue than enlighten.

Wayne 05.13.20 at 7:00 pm

Is this the standard of writing here? Take a phrase, re-word it twice, and island-hop your way into a caricature? The definition isn’t even a definition, it’s a accusation of motive.

Public Choice theory takes the economic assumption that people are normally driven by self-interest and applies it to governance as well. A Public Choice analysis might be that the median voter might get infected, but would certainly not die, and this will lead to resentment of the lockdown.

Really embarrassing, bad, embarrassingly bad read.

Lee A. Arnold 05.13.20 at 7:35 pm

#14: “It has nothing to do in the slightest with the public’s preferred choice.”

Well, no. Public choice theory is the application of the motivation of self-interested rationality to voting, and after that, the application of the same motivation of self-interested rationality to the actions of elected officials. See for example the first chapter of Tullock et al., Government Failure: A Primer in Public Choice (Cato, 2002).

Therefore public choice theory fails at those points where self-interested rationality does NOT apply to the choices of voters or to the actions of elected officials, such as choices and actions based upon altruism and social justice, and/or to other “questions that it is going to be systematically weak in addressing,” to quote the beginning of Henry’s 6th paragraph, above. Which he then goes on to address. Most of the comments here are similarly on the mark.

I would argue further that public choice theory also fails at the same point where Hayek’s theory of the “knowledge problem” fails: at the limitations of human cognition. Hayek supposed that the market is a better information processor than a government, because of limited and local knowledge. But prices are determined by supply and demand, and supply and demand are formulated out of the limited and local knowledge of producers & consumers — knowledge that we have just posited to be incomplete. So it’s a circular argument, and not much of the knowledge problem is truly solved by markets.

You might say that the same thing is true of voting (votes and prices being the two co-equal forms of systemwide decision-making). And that is mostly true, except for one thing. Voting is motivated by the individual’s expectation of unanimity, or at least of abiding by the consensus until the next election after that. This overcomes a knowedge problem for the time being, and thus frees individual rational choicemaking for other decisions. When combined with altruism and social justice, of course this becomes a powerful motivation to save time, to do the right thing, and to try to create moral agreement. We start with this motivation as young children and however the system subsequently disfigures us, it is often the public’s preferred choice.

Dan Culley 05.13.20 at 8:57 pm

OK, I guess you can say you have a disagreement with some major public choice scholars, but what “the public” wants doesn’t really have anything to do with public choice, which is about how the public sector chooses policies. In fact, it seems exactly backwards, because private power plays a key role in public choice: what you are describing is business interests capturing the regulatory response because of concentrated benefits and diffuse costs, exactly what most of public choice is about. Here that push is de-regulatory, but in many other places it is regulatory, to exclude competitors.

It seems weird to have a feud with the principle that governments are also made up of people who respond to incentives in choosing what becomes policy. And that fact can limit what realistically can be achieved with policy such that first best solutions for market failures may not be realistically be possible.

Chetan Murthy 05.14.20 at 6:22 am

Wayne @ 20 write:

I agree completely. Getting “the worst flu of your life” and being left with months-long debility, perhaps kidney failure, is no big deal, and I can see how the median voter would resent government’s attempt to prevent them from having this experience.

Yeap, yeap. It sure is a disgrace, Wayne, I’m 100% there with you.

And I should add: the median voter doesn’t give a toss about their parents or other elder relatives. Nosirree, they’d just as soon relegate ’em to an ice floe, and any, I say ANY attempt to prevent them from sending Nana and Gramps on that ice floe, well, the median voter will be Miiiighty Angry about that, I tell you!

bj 05.14.20 at 10:27 am

We could reduce that entire blog post down to the phrase, “but wage slavery!” This is an old argument, not a new one, and it has enough basis in truth to act as a good alternate model to the Public Choice take. I don’t object to the “wage slavery” argument, personally. I think it is sometimes a useful frame.

The post asks what the underlying game is, and doesn’t take the next step to identifying the actual underlying game. Why are people comfortable not going back to work? The reason they’re comfortable not going back to work is because they’ve been given a financial incentive to stay at home, in the form of bailouts and increased unemployment benefits and rent deferrals and such. They’re being paid to stay at home. And there may be justification for such a policy over the course of a month or two.

A useful corollary would be to look at developing economies, where they run a real, present risk of starvation due to stay at home orders, because they don’t have the sorts of buffers we have in the USA against economic destruction. We are tremendously privileged to have the buffer we have, but that buffer is not infinite.

So the real answer to “why the equilibrium would break down” is “the buffer runs out.” Unemployment funds vary by state, but under the current stress they’ll be empty in 24 to 48 weeks unless people come off of those rolls and get back into the workplace. This is far sooner than the 5 or more years it will take to gain herd immunity at current infection rates, and far sooner than the 12 to 18 months to develop a vaccine. Some people are looking this far ahead, and some are not. And the liberals looking this far ahead, that I have spoken to in depth on the issue, seem to think that we can simply just print money forever to solve the problem.

But money is just a barter proxy. It’s not wealth, it’s an exchange token. It doesn’t create the things we need to exchange.

The thing to watch is how the public opinion polls of Los Angeles fare through June, while they stay locked down and other areas don’t. One thing missing from the XKCD cartoon is dates on those polls. Quite a lot of people, including myself, bought into a month or two of “flattening the curve” to keep the ICUs from being overwhelmed, but absolutely did not buy into “flattening the curve” for two years to “find a cure.” The moving of the goalposts on that has floored quite a lot of people, and burned their trust in the policy makers who advocated curve flattening. Put simply, those polls are probably old, and probably going to dramatically change once this new goalpost is planted in the ground.

rjk 05.14.20 at 1:00 pm

So far, public sentiment seems to be pro-lockdown. This is unsurprising, insofar as the lockdowns in most areas followed both public protests and steep declines in economic activity, voluntary cancellation of events, and so on. For those governments which held out longest, the final straw seemed to be the voluntary cancellation of major sporting events (NBA, EPL in particular). In simple terms, the public does not have confidence in the safety of public spaces, is choosing to avoid them as much as is possible, and supports efforts to ensure that others do so too.

This runs contrary to the notion that the lockdown is something that has been imposed on the public, and as such it disrupts the simple narrative of big government telling the little people what they’re allowed to do. The anti-lockdown protests are fringe pursuits, at least for the time being.

There has been a definite attempt by some in the UK to push for a swifter re-opening, but this also struggles with the reality: even if Boris Johnson told everyone it was perfectly safe to go back to work, to the shops, and to the restaurants on Monday morning, few would actually do so. Those compelled by economic necessity might, but nobody who has any choice in the matter would join them. This can lead to the conclusion that the solution is to create the necessity, by withdrawing the furlough schemes and the (slightly) more generous benefits regime recently instituted. This has been resisted, again for the time being, perhaps for being a little too obvious.

In the absence of coervice methods, both Johnson and Trump are stuck in a bind: to get out of the crisis requires that they inspire confidence in their respective publics. They have to make people believe that it’s safe to go out and resume a semblance of normality. As partisan leaders, they might struggle to command the broad-based trust that would enable them to do this by persuasion alone. The alternative is also hard to imagine: that they demonstrate the sheer competence at managing the situation that people conclude that safety has been restored. Cowen clearly favours this approach, under the banner of “state capacity libertarianism” (to his credit, this was something he was talking about before the crisis unfolded).

Perhaps it’s useful to think of the public (or a section of it) as being on strike until safety conditions are improved. It’s a genteel strike, with no picket lines and barricades, but you can see the uncertainty it has caused in the minds of the political leadership. They’re really not sure how to play this one. I think they’re going to try exhortation and sloganeering, but when that doesn’t work then I’m not sure they can afford to kick the can far enough down the road that they get bailed out by a vaccine. A moment of truth awaits!

Lee A. Arnold 05.14.20 at 1:01 pm

Dan Culley #22: “…that fact can limit what realistically can be achieved with policy such that first best solutions for market failures may not be realistically be possible.â€

But the ultimate fact that limits what happens, is NOT that “governments are also made up of people who respond to incentives†as you wrote, but rather that voters don’t have enough knowledge to choose better leaders. (And better leaders, if and when they are chosen, don’t have enough knowledge to properly construe the social and economic problems they are meant to solve.) Voters — individuals — don’t have enough knowledge due to time limitations, cognitive limitations, the increasing complexity of the system, misinformation, and deliberate false propaganda. There are limitations inherent to the individual and limitations formed by power interests and elites.

These limitations also apply to producer and consumer behavior in the market. Thus public choice misconstrues the difference between markets and governments: the most important difference is not the “knowledge problem†(because that problem is the same for both) but that markets are better at facilitating the division of labor, and governments are better at facilitating equality and justice.

Public choice theory corralled voting failures (e.g. Arrow impossibility theorem) and government failures (log rolling etc.) into a conceptual scheme, and that is intellectually interesting. It is descriptive not predictive. Most of its descriptions have analogies in business management, so it could be broadened into a theory of central (or institutional) failures of all kinds; some correlated to voters, some correlated to price signals received by the firm.

Beyond that, public choice is intellectually suspect because most of its practitioners start from normative judgments in favor of markets, as Henry and Brad DeLong point out. Of course this is nothing new; it began with the politicization of economics in the 19th Century, shown in The Political Element in the Development of Economic Theory by Gunnar Myrdal (1930, English trans. 1953) — Myrdal won the Nobel same year as Hayek — and is updated to today in Where Economics Went Wrong: Chicago’s Abandonment of Classical Liberalism by Colander & Freedman (2019).

Lee A. Arnold 05.14.20 at 1:53 pm

anonymous #12: “It seems to be your position that workers should be able to stay home indefinitely and have someone else pay…employers should be bankrupted…there is a magical money machine so that nobody needs to work and yet somehow everyone can consume as much as they want.â€

This is a temporary emergency; employers should not be bankrupted; and the magical money machine was already bailing out the private financial markets, so why not everyone? since inflation in this instance can be controlled.

But this also gets us into a very long discussion of the fact that central banks are creating permanent bailout facilities to prop-up secular stagnation. Is this unavoidable? Is it a good or bad thing?

I tend to think that we should just face-up to the “stagnation” and stop feeding the financial behemoth beyond its direct investment in real supply. We are heading into a long era that needs focused quasi-governmental institutions to target a limited set of necessary human demands that have specific characteristics of supply and demand.

For example, healthcare: demand is finite (in fact it is well-predicted actuarially) so all necessary supply can be created without scarcity. “Quasi-governmental,” meaning single-payer: the supply-side (healthcare providers) can remain private (although on a public payment schedule) to try to preserve the market-enabled innovation and division of labor. And we can occasionally create the money for it, instead of relying only upon taxation, particularly when problems arise. We could also do it as a two-tiered system, with private add-on healthcare insurance for those with rhinestone-encrusted preferences.

Jon Murphy 05.14.20 at 3:08 pm

Where does the Rowley quote come from? I did a Google search but it just leads me back here and to and earlier post you did.

Henry 05.14.20 at 7:05 pm

The introduction to his Edward Elgar collection on Social Choice theory. A snip at UKP 672 (or 537.60 if you are prepared to settle for the ebook version).

Chetan Murthy 05.14.20 at 7:54 pm

There seems to be a tendency on the part of some commenters to conflate economic demand for (say) food, healthcare, various housewares, (maybe) construction/renovation with …. all the other services and products that are out there. The truth is, lots of those other services can be shut down for the next N months: bars and restaurants aren’t essential, hair/nail salons ditto, and on and on. Yeah, it kinda sucks. And (some) people argue that “yanno, back in the day,we went to school thru a driving blizzard of influenza and smallpox, and we didn’t cry none!” but those same people don’t seem to get that back then, there were no hair salons and for sure no Internet. So, y’know, the things that they’re clamoring for reopening, didn’t even -exist-.

There’s no reason why government shouldn’t decree that certain forms of economic activity just aren’t worth the cost in public health. Oh and btw, the idea that somehow the “market” can do it …. that’s risible. The market does what the rich want, b/c their wants are given a gynormous thumb on the scale. But when it comes to public health, every person is equal, because every person has only one life, only two kidneys, etc. So expecting the market to somehow come up with an optimal solution to “what to close, what to reopen” is a fool’s errand; it wasn’t designed for that.

Which brings us back to UI and the government “buffer”. Yes, there is a limit to how much the government can just print money and give it to people. But as long as the -basics- of survival are being produced (which is why the entire food & medical supply chain is essential), the government -can- print money forever [and, for good measure, should be upping taxes on the rich, ffs]. Again, it’s a question of whether enough of the essentials are being produced. And (just as in WWII) you can’t leave that to the market: because Elon Musk wanting his godforsaken helicopter WILL take precedence over 100 ventilators.

Peter T 05.14.20 at 11:46 pm

@24

“But money is just a barter proxy. It’s not wealth, it’s an exchange token. It doesn’t create the things we need to exchange.”

When Britain ran up a debt of 200% of its GDP over 25 years fighting and winning the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (and also grabbing a quarter of the world and building the first industrial economy), just what precisely was it bartering? What has been exchanged for the several trillion created by central banks in the wake of the GFC?

It reflects very badly on the profession if this chestnut still appears in economic texts.

Collin Street 05.15.20 at 12:07 am

I think it is obvious that those for whom safety is least expensive, will choose the most safety, and those for whom safety is the most expensive, will opt for less safety. However I do not believe there is any conflict between upper class and lower class on coronavirus issues. […] So it’s not a matter of rich people safely working from home and asking low-income workers to go back to work.

I mean, this is beyond parody.

“Distributional issues means that people will be forced to make differing choices about their personal safety, but there are no class issues here. Although I have just said that poor people will be unsafe and rich people will be safe [something that has nothing to do with class], it’s not just a matter of rich people working safely and poor people working unsafely”.

[educational systems subject to pressure by those with social capital will significantly underdiagnose moderate cognitive impairment among the children of those with access to social capital. This will leave such children without access to the toolkit to either reach the level of success their parents did or to understand the basis of their inability to do so, leading to confusion, resentment and anger, and to a blaming of the failure not on the actual-causative personal factors but on external social changes and in particular the visible manifestations of same such as architecture, migration, sexual expression, music and the like. Is my thesis, stated as succinctly as I can manage.]

Chetan Murthy 05.15.20 at 5:03 am

Collin Street wrote “I mean, this is beyond parody.” Indeed Gotta reach back for the hoary old ones, don’t we?

“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal bread.”

Zamfir 05.15.20 at 3:52 pm

Peter T:

”

When Britain ran up a debt of 200% of its GDP over 25 years fighting and winning the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (and also grabbing a quarter of the world and building the first industrial economy), just what precisely was it bartering? What has been exchanged for the several trillion created by central banks in the wake of the GFC?

”

Perhaps I am taking this question too literally, but I’d like to see if I can spell this out.

Right now, the economy is cutting back on “non-essential” production, mostly certain services. That is in principle a reduction of supply and demand together, with relatively limited impact on the “essential” production that is still going.

That essential production is just as capable of supplying the whole country with essential goods and services as before, and there is no “running out” reason why certain people would have to go without essentials. Everyone misses out on haircuts, no one misses out on food. Except where we are wrong, and certain supposedly non-essentials have an indirect impact on essentials (this gets more likely over time).

This goes wrong in practice though. The supposedly “non-essential” producers have no more income, even to buy essentials. This is directly bad for them, and goes further haywire as the “essentials” side will lose customers, etc.

In theory, the government can fix this directly. It taxes everyone the money that they would otherwise have spend on haircuts and otehr non-essentials, and gives that money to the hairdressers and other fuloughed workers (and businessmen and everyone else involved in non-essential production). Until the crisis is over.

That is to difficult to organize. So a simpler trick: the government prints extra money, adn uses that. That could go wrong in theory, as the people with “essential” income still have the money they saved on haircuts,without actual production to spend it on. The governemnt could do the war bonds thing, and borrow that money awayto balance it out again.

But in practice, we know that people in uncertain times want to stock currency away for the future. Instead of the war bonds thing, we can just as well let them keep the money. If there is nasty inflation in the future, the central bank can hoover up the currency again.

steven t johnson 05.17.20 at 12:27 pm

There are always two sides to hear, if not more, no? https://bleedingheartlibertarians.com/2020/05/what-is-public-choice/

Loathe as I am to admit it, Brennan is correct that picking a quote from one person isn’t really enough. And the larger point he makes, that public choice analysis of the competence of government to resolve supposed market failures applies in all cases, by definition. And the definition, the internal incongruences, or whatever, are not up for debagte.

That’s not really relevant to the Hanson case, which to my eyes is BS designed to confuse the issues, done for Trumpery. But of course, there are no issues of corruption in the academy and any who make such evil-minded claims are sinners against scholarship, not peers like Brennan or Hanson. It is entirely unclear how a valid case against government monopoly of education isn’t also a valid case against government monopoly of health. And certainly government monopoly of investment is the cardinal sin in the eyes of everyone else here.

But being uncouth, I will say that so far as I can judge, the confusion about what the public is is an inescapable part of all acceptable economics. The “public” is who always benefits from any technological innovation, all forms of free trade, deregulation, privatization, national defense…why, the same “public” is the definition of national interest! Brennan is interesting to read because he is so Emersonian (“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”) It makes him very good at spotting inconsistencies, if not to make a positive case.

Comments on this entry are closed.