THE UCLA ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES CENTER is the largest and one of the longest-running research centers of its kind in the country, with more than a half-century of history behind it. But the center might never have existed if not for the persistent and organized activism of Bruins on campus in the late 1960s.

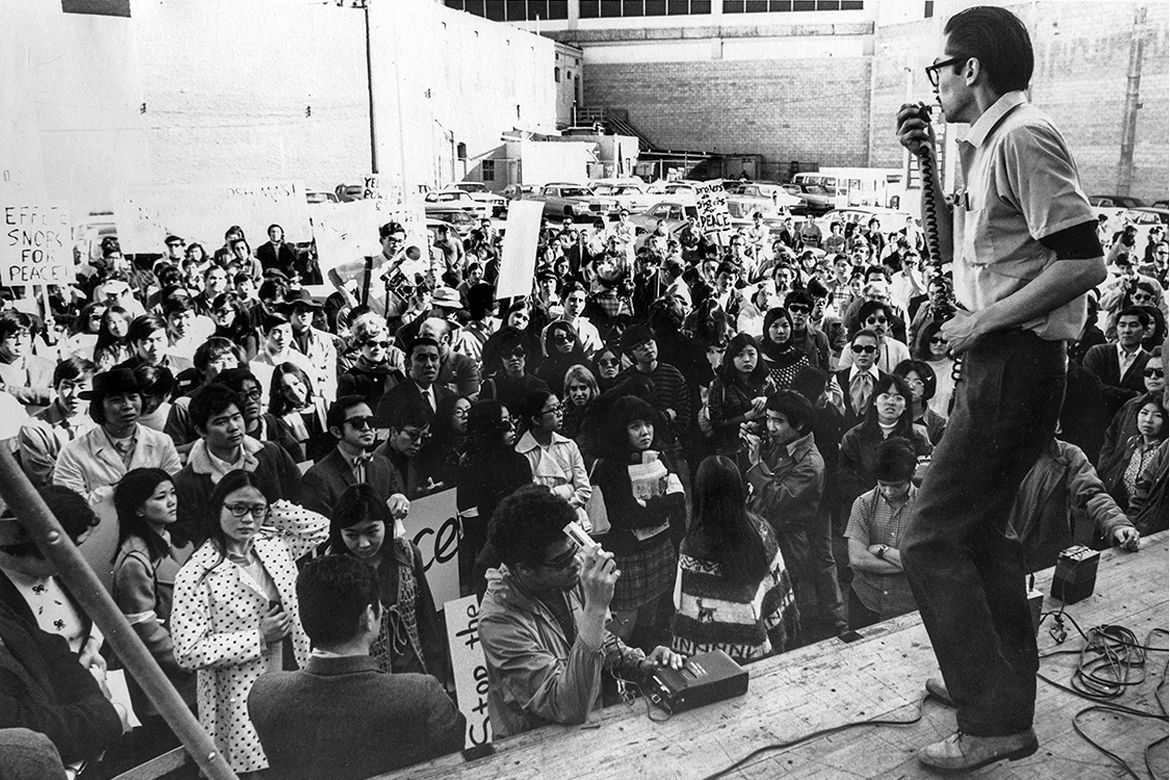

In 1969, when UCLA initially planned the formation of its ethnic studies centers, there were centers for Native American, Chicana/o and Black studies, but Asian American studies were noticeably absent. To voice their objections, student activists picketed Administration Hall (now Murphy Hall) to publicly criticize the omission, and a steering committee was formed to petition for its inclusion.

“We were inspired by the San Francisco State student strike [in 1968–69],” says Suzi Wong ’70, who served as the executive chair of the steering committee. “Fortunately, UCLA students had the support of faculty and community leaders who also saw that Asian Americans deserved to have their own center.”

The committee members collaborated on the “Proposal for an Asian American Studies Center,” which summarized their goals: “The Center will hopefully enrich the experience of the entire university by contributing to an understanding of the long-neglected history, rich cultural heritage and present position of Asian Americans in our society.”

In June 1969, then-Chancellor Charles E. Young M.A. ’57, Ph.D. ’60 submitted the proposal to the Committee on Budget and Interdepartmental Relations and the Committee on Education Policy, writing of his “conviction that the early establishment of these [ethnic studies] centers is a matter of the highest priority.”

About a month later, the Asian American Studies Center was officially established as part of what later became the UCLA Institute of American Cultures, which also comprises the American Indian Studies Center, the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies and the Chicano Studies Research Center.

“UCLA students had the support of faculty and community leaders who also saw that Asian Americans deserved to have their own center.”

Suzi Wong ’70, executive chair of the steering committee

“Following San Francisco State, which gave birth to the nation’s first school of ethnic studies, UCLA was among the first wave of Asian American studies programs to be established,” notes Karen Umemoto M.A. ’89, the Helen and Morgan Chu Endowed Director of the Asian American Studies Center. “And it has continued to grow.”

A new identity

The term “Asian American” was still fairly new at that time. Its first use was in May 1968, when UCLA alumnus Yuji Ichioka ’62, his wife, Emma Gee, and others founded the Asian American Political Alliance. It was the first of its kind, uniting Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Filipino Americans, among others of Asian ancestry, to fight for political and social action together.

“There were so many Asians out there in the political demonstrations, but we had no effectiveness. Everyone was lost in the larger rally,” the late Ichioka once said. “We figured that if we rallied behind our own banner, behind an Asian American banner, we would have an effect on the larger public. We could extend the influence beyond ourselves to other Asian Americans.”

Not only did the term “Asian Americans” unify previously disparate groups, it also shifted how people saw themselves. Before Ichioka coined the term “Asian American,” the predominant description for those of Asian descent was “Oriental.” But the problem with that word is that it’s in relation to its antonym, “Occidental,” which refers to the Western world and centers on Europe.

“The term ‘Asian American’ underscores the fact that we are all Americans,” Umemoto explains. “We’re not perpetual foreigners, but we’re not like other Americans. Asian American student activists recognized their shared histories as laborers who made important contributions in the face of racism and discrimination.”

After the Asian American Political Alliance disbanded, in 1969, Ichioka returned to UCLA, where he taught in the Department of Oriental Languages. There, he continued his activism, co-chairing the steering committee that helped establish the Asian American Studies Center and becoming the center’s associate director. That same year, Ichioka taught UCLA’s first Asian American studies class.

In 2004, following the death of Ichioka in 2002, the center established the Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee Endowment for Social Justice and Immigration Studies, honoring the beloved professor and his wife for their contributions to the advancement of Asian Americans.

Leading the world

Today, UCLA’s Asian American Studies Center is thriving. The center and the Asian American Studies Department together represent the largest concentration of faculty who study the Asian American and Pacific Islander populations in the entire world.

The center’s long-standing Amerasia Journal is one of the leading interdisciplinary journals in Asian American studies, establishing the field as a relevant area of scholarship, teaching, community service and public discourse. In addition, the center houses expansive special collections and archives related to Asian Americans and their experiences.

“When we wrote our proposal for the Asian American Studies Center, we were strategic,” Wong says. “Since part of UCLA’s mission is research, our proposal highlighted research. We argued that in order to make the research mission more honest, UCLA needed to include Asian Americans.”

During a recent visit to UCLA, Wong expressed joy at the vitality of the center: “I am grateful to the succeeding five decades of participants, supporters, alumni and donors who stewarded our founding vision and renewed its currency through their own passion, dedication and commitment.”

Read more from UCLA Magazine’s April 2021 issue.