The OTR truckload driver count is at an eight-year low, and traditional solutions to solving the driver shortage aren’t working. It’s time for all carriers to start investing and innovating in new solutions. Here’s my take on what I see – and how carriers can make the needed shifts.

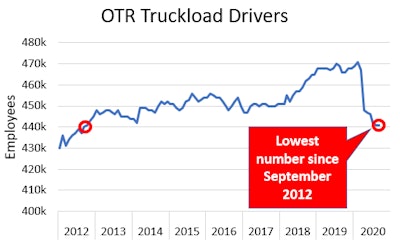

In February 2020, the U.S. government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) OTR truckload driver count hit an all-time high of 471,000 drivers. The very next month – on March 19 – California announced the nation’s first stay-at-home order due to the COVID-19 epidemic. One month later there were 23,000 fewer drivers. By August, the industry had lost an additional 7,000 drivers and the OTR truckload driver count hit its lowest point since September 2012, when the industry was still clawing out of the Great Recession.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the OTR truckload driver count is at an eight-year low.

Data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the OTR truckload driver count is at an eight-year low.This remarkable fluctuation comes after five years (from 2013 through 2017) of the industry consistently averaging approximately 450,000 drivers. We had the strongest freight environment I’ve seen in my 30-year career in 2018 and the industry added 20,000 drivers. In the past six months, the industry has lost 30,000 drivers.

This drop in the number of drivers has led to decreasing truck counts at nearly all the big public truckload carriers. Among the eight public truckload carriers that report truck counts, total truck count decreased in the past year by 2,287 trucks (3.6%). There’s plenty of great freight with great rates and carriers have plenty of trucks and trailers. Carriers aren’t shrinking because they want to. Every carrier mentioned the struggle to recruit and retain drivers in their earnings releases.

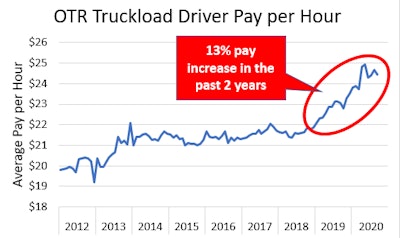

Driver pay has, on average, increased 13% per hour worked — and yet, the industry’s still struggled to grow the driver count.

Driver pay has, on average, increased 13% per hour worked — and yet, the industry’s still struggled to grow the driver count.In recent months, many carriers have announced pay increases for drivers. But this obviously isn’t a recent phenomenon. According to the BLS database, driver pay per hour has been steadily increasing for two years. Today’s average driver is paid 13% more per hour than the average driver from 2 years ago.

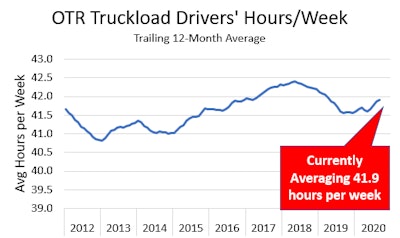

Currently, the BLS says the average driver works 41.9 hours per week. Interestingly, from 2014 to early 2018, the average hours worked per week steadily increased from 41 to 42.4 hours per week while the average pay per hour stayed fairly constant. Drivers’ take-home pay was keeping up with inflation, but it came from working more hours rather than pay increases.

A few interesting correlations between the driver count, driver pay and hours worked. Things get really interesting when you compare and contrast these three charts.

• Pay increase timing: Driver headcount, and average hours worked per week, increased steadily throughout 2018 while hourly pay remained fairly flat. Carriers were able to attract more drivers simply by posting more openings at roughly the same pay. But in late 2018, driver headcount stopped growing and carriers responded with the biggest pay increase in years.

• More money but fewer drivers: Driver pay steadily increased throughout 2019 much faster than inflation or average pay in the U.S., yet driver count barely increased. In 2020, driver pay has continued to increase at a pronounced rate while driver headcount has plummeted.

• More money, fewer hours: When driver pay began to increase in mid-2018 through 2019, there was a corresponding decrease in average hours worked. Perhaps some of this comes from the industry adding too many drivers (leading to less available work per driver). Another possible explanation is that when drivers are paid more per hour, they don’t have to work as many hours to get their desired weekly income.

This suggests to me that pay increases alone are not enough to increase our driving population. And this is also why I’m suggesting that today’s driver shortage is different from the shortages we’ve seen in the past.

It’s worth noting what’s been happening in the spot market this year. In February, when the driver count hit an all-time high, spot rates were in a free-fall and bottomed out at an average of $1.79 per mile, according to DAT. At that point, there was clearly more capacity than freight. But, when COVID hit and the number of drivers plummeted, spot rates increased immediately as shippers struggled to find someone to haul their freight. In the latest DAT report, dry van spot rates have risen 68 cents since February to a record high of $2.47. With higher rates, carriers have continued to increase driver pay, but with no improvement in the number of drivers.

Addressing the bottleneck. Focusing on the bottleneck is a fundamental strategy for turning around and improving businesses. A bottleneck is the primary factor holding back your throughput. You can spend money increasing bandwidth before or after the bottleneck, but if you don’t increase bandwidth at the bottleneck you won’t see any improvements in throughput. As the old saying goes, “A chain is only as strong as its weakest link.”

Drivers are the bottleneck right now. Carriers have plenty of equipment and the market is full of good-paying freight. The number one thing holding carriers back from hauling more freight and growing their business is the inability to recruit and retain drivers.

As I talk to fleets throughout the country I’m surprised by how many of them are not focused enough on drivers. Everyone is feeling the effects of the driver shortage, and everyone says they’re doing “more,” but too few carriers are focused on implementing effective solutions that will solve it.

Here are the strategies I see as effective means to that end:

Update your business model. Our industry is moving too slow in embracing a younger and more diverse workforce.

When I talk to some of the veterans of our industry I hear complaints about “this generation” and their inability to be successful drivers “like our generation.” They view the attitude and expectations of new drivers as a problem that needs to be fixed. It’s as if they’re saying, “We need to teach them to be like us.”

Trying to teach the next generation to want what we wanted, and do what we did, is a losing battle.

Rather than trying to change the drivers it’s time to focus on changing the job. There’s a lot to love about trucking. Many people enjoy the connection between man and machine while driving a powerful tractor hauling a 22-ton load and backing a 53-foot trailer.

Schooling is minimal, you get to see the country and you don’t have a boss looking over your shoulder or annoying coworkers crammed into the seat next to you. You don’t have to wear uncomfortable clothes and talk to people all day or do exhausting manual labor, yet we are struggling to attract and retain drivers.

Predictable work. Predictable pay. More home time. I believe the solution lies primarily in making the job (and pay) more predictable and increasing home time.

It’s stressful for our drivers when they don’t know if they’ll make enough money this week to pay the bills depending on whether or not they get a good load or when their load empties. You would think that drivers living in their trucks and being on the road for weeks at a time means they’re working a lot of hours, right? Wrong. The statistics above show that our drivers are only getting 42 hours of work each week (and those aren’t even all driving hours). This low number is supported by looking at the utilization of public carriers who struggle to get 2,000 miles per week on trucks that generally average 50 miles per hour when being driven.

In talking to people in the industry, there are several ideas to address this, such as partially moving away from a pay-per-mile model to a pay-per-hour or minimum-guaranteed-pay model. Instead of getting drivers home every couple weeks, we need to start getting them home every week and every day.

The traditional business model for over the road truckers has been “shippers pay us by the mile, so we pay drivers by the mile.” When loads get delayed, some shippers often don’t pay carriers anything more, so carriers don’t pay drivers more. This model keeps shippers happy and carriers profitable, but drivers hate it.

It’s time for carriers to start thinking differently. Electronic logs make it easy to pay by the hour. Drop-and-hook trailer pools keep drivers moving instead of sitting for hours to get loaded and unloaded. Sophisticated computers make it easier to relay loads from one driver to the next and keep drivers close to home. Hub-and-spoke models create lots of local dray jobs and consistent middle-mile relay opportunities while also increasing equipment utilization and allowing carriers to purchase less-expensive daycabs rather than sleeper trucks.

Remember when carriers were responsible for providing pallets? Weren’t you glad to see the industry shift to relying on third parties for pallets? What if we did the same thing with trailers?

On railroads and boats, it’s common for the boxes holding the freight to be owned by someone other than the company providing the power. Could we do the same with tractors? Think of the possible efficiencies that could come from shared trailer pools and power-only dispatching that allows one carrier to relay a load to another carrier. Shippers could load any trailer and then pick available tractors that have the hours. This could limit the need to look into the crystal ball when trying to predict which shippers will have a load or which carriers will have a driver. With these efficiencies, it could be so much easier for drivers to work a normal schedule and be home every day.

Shippers and receivers need to help. Shippers and receivers need to be part of the solution by keeping their commitments. Warehouses need to be properly staffed to ensure there’s always enough help to get trailers efficiently loaded and unloaded. Start using trailer pools instead of live loads and unloads. Give drivers more flexibility on appointments and start paying for detention. Consider hiring and paying lumpers directly instead of expecting drivers and carriers to manage this detail.

Stay focused. It will be uncomfortable but you can do it. You have to do it because the old ways aren’t working. Don’t be the next Blockbuster, K-Mart or J.C. Penney to be replaced by Netflix or Amazon – companies who view problems as opportunities to bring new solutions.

Just because we’ve done something one way for decades doesn’t mean we should keep doing it that way. The current freight and rate environment has given us an opportunity to push for improvements on behalf of our drivers.

Don’t spend all of your rate increases on new trucks and trailers, new software and more advertising. Give your drivers a generous pay increase, but then do more. Invest more in little things like making sure the trucks are thoroughly serviced, detailed and fueled before assigning a driver. Give drivers meals and gifts to let them know they are appreciated. Give them company swag to feel more connected to your team.

Start making big investments in disruptive innovations. One safe bet is increasing and improving the staffing in your shops and driver support to provide better, faster service to our drivers. An even better bet is to begin experimenting with ways to improve predictability of work/pay and increasing home-time through business model changes. Ask your people for new ideas. Have an internal Shark Tank program. If you come up with great ideas but don’t have the skills to implement them, hire consultants or new employees who can help.

Richard Stocking is the founder and CEO of DPX Consulting, a transportation consulting firm that helps fleets with strategic operational improvements and M&A activity. He is also the former president and CEO of Swift Transportation.