I. Introduction

[P]ostmodern thought will return to spatial metaphors, even though inspired by new spaces and spacialities.

– Boaventura de Sousa Santos, 1987The coexistence of multiple and overlapping spheres of legality poses challenges to the concept of legal order. Observations such as a blurred distinction between domestic and international law, as well as between public and private law, hybrid law-making processes, a broadened perception of legal actors, the dissolution of pre-existing boundaries and the creation of novel boundaries in law raise fundamental questions for the concept of legal order. One can ask about the extent to which legal orders are permeable or closed to influences from the outside and whether the concept has a territorial dimension – including whether it is based on the territoriality of the state. The above observations also challenge classical conceptual features of the concept of legal order, such as its internal structuring function oriented towards coherence.

In light of these challenges for the concept of legal order, this article engages with an alternative notion: the legal space. This is a notion that is being used more and more frequently, including in the general legal pluralist literatureFootnote 1 and as part of specific notions such as ‘European legal space’.Footnote 2 Employing this notion explicitly or implicitly attempts to overcome some of the limitations of the concept of legal order, including its often state-related understanding, its coherence claim or its perceived closure towards the external sphere. Bodies of law such as global administrative law, corporate social responsibility law, platform law created by digital platforms and the lex sportiva used by the Court of Arbitration for Sport are difficult to assess within the classical framework of legal order. When the term ‘legal space’ is used instead, this highlights the need for an alternative or at least complementary concept. However, so far the notion of legal space is conceptually underdeveloped. It is often used rather intuitively to address the challenges of overlapping spheres of legality, but without much theoretical underpinning. The analytical potential of this notion has not yet been elaborated. The features of a legal space and the thrust of its analytical function require further consideration.

In this article, I explore the potential of this concept. I show that legal space is a notion that can serve as an alternative concept to legal order in view of the limitations of the latter. This is especially the case in the context of multiple legalities, a term referring to the coexistence and interaction of legal domains as they are broadly understood.Footnote 3 At the same time, I argue that the way in which the notion of legal space has often been conceived needs to be critically assessed. In particular, not only the notion of legal order but also legal space has, for the most part, been used in a territorial or ‘political-geographical’ way.Footnote 4 In contrast, this article argues for a non-territorial concept. Inspired by the topological notion of space, it is concerned with understanding the ways in which legalities interact rather than with ‘measuring’ the spatial dimensions of the sphere formed by legal elements.

Beyond this aspect, the notion of legal space suggested here comprises various features that are guided by concepts from topology, a branch of mathematics that analyses the qualitative nature of spaces. This approach has been adopted in an interdisciplinary manner, including in various disciplines of social science.Footnote 5 A topological perspective can offer novel insights into a variety of subject matters, and it can be a fruitful approach for legal thinking as well. In the context of multiple legalities, a topology-inspired approach to legal space provides categories to conceptualize and characterize sets of legal elements and their interactions, including phenomena such as overlaps and hybridity. It is conceptually less constrained than the concept of legal order, and thus allows to address various bodies of law, ranging from classical domestic law, EU law and international law to the abovementioned examples global administrative law, corporate social responsibility law, platform law and lex sportiva. It provides a novel perspective on all these bodies of law and is specifically useful where the concept of legal order reaches its limits. More generally, a topology-inspired notion of legal space offers an analytical toolkit for better understanding multiple legalities and specifically phenomena of intertwinement of legal spaces. It allows us to capture how the nature of a legal space can change if its intertwinement with other spaces intensifies or loosens.

To develop this approach on the concept of legal space, I first engage with existing notions of legal order and legal space, and discuss the extent to which they are able to address the challenges of multiple legalities (section II). I then sketch out a topology-inspired notion of legal space (section III). After introducing topology’s guiding ideas, I show that this approach can contribute to conceptualizing, in a novel manner, the inner structure of legal spaces, the boundaries of these spaces and the interrelations with other spaces. I conclude by highlighting the benefits of a topological understanding of legal spaces (section IV).

II. Legal space as an alternative concept to legal order

The current discussion of multiple legalities is constrained by the notions used as reference points. Although it is still referred to in many contexts, including to capture novel forms of legality, the notion of legal order has considerable limitations. At the same time, alternative notions deployed by some authors, including the notion of legal space, have not yet been sufficiently conceptualized, so far narrowing their analytical potential. Both these aspects are addressed in turn.

Limitations of the notion of legal order

Developing an alternative to the notion of legal order is necessary because this concept is limited in what it can achieve for theoretical legal analysis. In particular, the notion of legal orderFootnote 6 is not fit for purpose when it comes to conceptualizing the intertwinement of legal spaces or the entanglement of legalities.Footnote 7 ‘[T]o view and interpret [new configurations] through an old lens’ is problematic when this means doing so without conceptual instruments that can capture the specificities of these ‘configurations’ and forgoing the opportunity for ‘reimagining’ these instruments.Footnote 8 In this section, I outline some of these limitations, basing the analysis on a more in-depth engagement with this notion elsewhere.Footnote 9

First, limitations stem from assumptions that are connected to the legal order’s dimensions and boundaries. According to these assumptions, legal orders are bounded and their dimensions are measurable. Legal norms belong to a certain legal order or they do not – there is an inside and an outside of the legal order.Footnote 10 Only legalities for which one can determine such a boundary between the inside and the outside are defined as legal order. In contrast, legalities that do not have a clearly discernible boundary do not fit into this frame. Further, the understanding of these boundaries is shaped by the fact that the ‘conceptual apparatus’ that focuses on the legal order or system ‘has been produced on the backdrop, and during the heyday, of the modern state’.Footnote 11 Based on this state-related approach of ‘modern law’, the legal order is shaped as a territorially defined and delimited concept.Footnote 12 Although it would be possible to conceive of legal order in a de-territorial manner,Footnote 13 the territorial understanding is still predominant.Footnote 14 It corresponds to the idea of a ‘neat, territorially coded mutual exclusivity of jurisdiction’.Footnote 15 For most of the twentieth century and often today, this territorial dimension of legal order has been and still is explicitly linked to the territory of the state or, more broadly, to the authoritative regulatory power of certain public actors.Footnote 16 Accordingly, the territorial dimension of legal order can be constituted by a single state (domestic legal order), by the territories of a group of states (for example the legal order of the European Union) and even by their totality (such as arguably for the international legal order). Such an approach makes it difficult to assess certain forms of legality that do not fit into this frame. This is the case for forms of legality that are not or not exclusively created by the state or other public actors.Footnote 17 Law that is created by private or hybrid actors is, for the most part, not linked to a clearly defined territory – and is thus detached from territorial categories.Footnote 18 For example, as observed by de Sousa Santos, ‘each multinational corporation or international economic association has its own personal legal quality and carries its law wherever it goes’.Footnote 19 In addition, the intended spatial reach of norms can be different from their de facto regulatory impact. An example of the latter would be the ‘extraterritorial’ norm-shaping effect of certain EU regulations, such as in the field of data and privacy regulation. Moreover, one can observe that clustering of legality has moved, in several contexts, from a territorial to a functional point of reference. Legalities are delimited by functional rather than spatial boundaries. Law is fragmented ‘along issue-specific rather than territorial lines’, as exemplified by regulatory regimes for environmental and health issues or the private regulation of the cyberspace and of transnational commercial activities.Footnote 20 Some authors have described this as a ‘deterritorialization’ of law.Footnote 21 One reason for such a deterritorialization is the increasing amount of regulatory objects that cannot, or can only with difficulty, be linked to any territory – an aspect that is particularly salient in the case of digitalized data and its fluid location.

Based on an understanding of bounded legal sphere, the issue of external exclusiveness comes into focus – that is, whether and to what extent legal orders have an impermeable or permeable boundary. The question here concerns the extent to which it is possible for elements from outside a specific legal order to influence or interact with elements belonging to this legal order. The state-related modern law understanding of legal order is rather exclusive. Conceptually closing the legal order to the outside, normative influences from or towards the outside are excluded, limited or at least considered to be controlled by the legal order itself. According to this understanding, each legal order self-regulates its potential connection with external legal elements. Classical private international law as well as dualist understandings of the relationship between domestic and international law reflect this approach. This emphasis on external exclusiveness creates tensions when phenomena that indicate permeability or ‘legal porosity’ are analysed through this lens.Footnote 22 Based on the notion of legal order, it is difficult to conceptualize many of the various ways in which elements from different legal orders can interact. Considering the ‘exponential increase in the density of transboundary relations’,Footnote 23 the concept of legal order falls short of capturing an important aspect of legal reality.

In addition, considering legal orders to be ‘closed’ towards the outside also implies an autonomy claim. Legal orders are understood as being independent from each other regarding their bindingness, law-creation and application. The idea of legal order as a self-sufficient or ‘autopoietic’ system highlights this claim.Footnote 24 According to this approach, legal orders consider themselves to be complete so that there is neither a need nor room for legal elements stemming from the outside. This includes that legal orders have the ability to enforce their rules without having to seek validation by another entity.Footnote 25 As a result, legal orders are thought to be clearly separated from each other. They are perceived as disconnected even if their coexistence is acknowledged. This perception stands in contrast to one of the key claims of legal pluralism that ‘laws overlap and interact in certain ways’.Footnote 26 The interrelations and potential interdependencies between the elements stemming from different legal orders are not addressed by the concept of legal order. It does not provide sufficient tools for conceptualizing overlapping and intertwined spheres of legality, or ‘interlegality’.Footnote 27 Moreover, it creates an incentive for thinking only of a relationship between legal orders rather than of interrelations of legal norms. It invites us to put entire legal orders into a relationship with each other, specifically in the sense of conflicts between them.Footnote 28 But not all norms within one legal order relate to the norms of another legal order in the same way. Instead of thinking of legal orders as monolithic blocs, more nuanced approaches regarding the interrelations of norms are necessary to conceptually capture the multiple phenomena of intertwinement.Footnote 29

The second set of limitations of the notion of legal order stems from assumptions that are connected to the legal order’s internal sphere. The assumption of internal coherence is probably the most salient among them: ‘coherence is the legal value most closely connected to the notion of order’.Footnote 30 It ‘requires that the set of norms makes sense as a whole’.Footnote 31 Legal order thus implies a rigid understanding of internal structure. Although this structure can have various forms – for example, a Kelsenian ‘Stufenbau’ and other forms of hierarchies, or a system of primary and secondary norms, the elements within the order are considered to be structured in a coherent way. They are considered to form a unity. This coherence assumption – as well as the coherence expectation – makes it difficult to apply the notion of legal order to spheres of legality that do not demonstrate the expected degree of coherence.Footnote 32 Endeavours to develop notions such as ‘global legal order’ or ‘transnational legal order’ have struggled with this assumption.Footnote 33 Accordingly, for some ‘messy’ networks of legal norms and actors that have been singled out as analytical objects, applying the notion of legal order has not even been attempted. Recent examples include hybrid fields such as ‘platform law’ governing legal questions raised by transnational online platforms such as Facebook and Twitter or Airbnb and Amazon,Footnote 34 or ‘corporate social responsibility law’ governing the human rights obligations of businesses.Footnote 35 Further, the coherence assumption is closely connected to the kind of actors that are considered relevant law-creating and law-applying actors. The smaller the group of actors that one takes into account, the easier it is to construct coherence, or a perception of coherence, regarding these actors’ activity. Inversely, multiple (kinds of) actors – including private and hybrid actors – make it harder to construct such coherence claims. When analysing law through the lens of the legal order, one risks seeing only that which fits the coherence assumption and ignoring the rest.Footnote 36 If the notion of legal order is a ‘reconstruction extrapolating from the given material’,Footnote 37 the ‘given’ material is in turn reconstructed through this analytical lens.

Moreover, the notion of legal order focuses on norms, leaving only limited room for an actor-related understanding of law.Footnote 38 Consequently, approaches that construct law with regard to the behaviour of actors do not relate to the notion of legal order. For example, accounts that understand law as ‘concrete patterns of behaviour’Footnote 39 and as based on ‘communities of practice’Footnote 40 that determine the law in an interactional and intersubjective process focus on intersubjective norm construction rather than the formalized understanding of law inherent to the notion of legal order. When analysing law through the lens of legal order, this dimension of legality remains unexplored.

Relatedly, it also limits the analytical potential of the notion of legal order that legal orders are perceived to be – at least to some extent – static in nature. When focusing primarily on norms that are understood as static, this characteristic is translated to the resulting picture of the legal order. Notions such as the ‘momentary legal system’, describing the law in force at a given moment in time, presume it is possible to clearly distinguish between law that is in force and law that is not yet or not any more in force. This assumption contrasts with certain understandings of law, such as law being a ‘continuous process of authoritative decision’.Footnote 41 More generally, the concept of legal order does not provide analytical categories to conceptualize structural change. Although changing norms are accepted as facts, again the notion does not include a conceptual apparatus to capture the extent, impact and nature of changes in law.

In sum, the notion of legal order is neither sufficiently broad nor sufficiently detailed to provide an analytical tool for multiple forms of legalities and intertwinement. It is not broad enough to address all relevant actors and all relevant forms of legal norms and practice, including those that are ‘more open, more horizontal – more web than pyramid’.Footnote 42 And it is not detailed enough to provide categories for understanding the various kinds of overlapping legalities, intertwinement and normative interaction, as well as the transformative processes that take place when legal norms and actors interact.

Requirements of an alternative concept

To address phenomena of multiple legalities, we need concepts and categories that will allow us to better understand and represent these phenomena.Footnote 43 The notion of legal space can contribute to filling the current gap. It aims at overcoming some of the above-mentioned issues that are characteristic of the concept of legal order. On the one hand, legal space is a more inclusive notion. It allows us to analyse a broader variety of legal phenomena, including some that the notion of legal order does not capture. In this regard, the notion of legal space is a prominent analytical tool for legal pluralist assessments of law. It can describe bodies of law that do not fulfil the (perceived) criteria of a legal order, such as law that is not state-related; law resulting from private rather than public regulation; law that does not fall into classical categories such as domestic and international law; bodies of law that are not perceived as sufficiently autonomous and/or coherent to form a legal order; fluid legal phenomena not captured by the static dimension of legal order; or a body of law lacking clear boundaries. On the other hand, legal space has the potential to provide categories for understanding the various kinds of overlapping legalities and forms of intertwinement, as well as the related transformative processes that induce structural changes. Such intertwinement and its effects are still under-theorized.Footnote 44 Section III develops this aspect.

A concept of legal space that can implement these aims requires certain key features. The scholarly discussion reflects these requirements.

First, the concept should be able to capture both the features of legal spaces, as well as their overlaps and intertwinement. So far, these dimensions are often addressed separately. An example is the influential notion of interlegality shaped by de Sousa Santos. According to this author, interlegality is ‘a result of interaction and intersection among legal spaces’.Footnote 45 This is one of the first approaches conceptualizing the intertwinement of legal spaces. However, this notion only addresses one of the above aspects: ‘it speaks to contacts between legal orders or spaces, but does not itself decide what counts as a legal order’ or space.Footnote 46 Combining both aspects would not only allow for a holistic analytical framework, but it makes it possible to conceptualize how these aspects influence each other. As section III highlights, the features of a legal space can change if its intertwinement with other spaces intensifies or loosens.

Second, the concept of legal space should not be limited to a territorial understanding. Considering space only to be territorial in nature would perpetuate the above-mentioned limitations of the concept of legal order that relate to its territorial dimension. Instead, the notion should accommodate functional, practice-related and other non-territorial forms of clustering law. However, in light of the conventional meaning of ‘space’, the notion of legal space has so far often been used with a distinct territorial dimension. An example of such a territorial understanding of legal space is the notion of the ‘European legal space’ as suggested in the European law context.Footnote 47 Aiming at doing away with some of the criteria of a legal order, this is a notion used flexibly to describe a space of which the extension varies according to the policy field – such as in the context of the Schengen area, Eurozone, EFTA, European Union or the space formed by the Council of Europe regime applicable to (geographically) European states. Reflecting on its territorial dimension, this notion of European legal space is meant to describe the following: the territoriality of the domestic legal orders is ‘substantially transformed’ and the notion of legal space conceptually combines these territories into a new legal territoriality of the space.Footnote 48 This approach does not dissolve or abandon the territoriality of law and of the legal order. Rather, the suggested notion of legal space adds a new territorial entity (the European region) to the existing entities of the domestic legal orders concerned. Other uses of legal space are less explicit in their territorial dimension, but they do refer to it. For example, when de Sousa Santos determines ‘three different legal spaces’ – ‘the local, the national and world legality’ – this understanding still has a territorial connotation. A territorial understanding of legal space has raised critiques. It has been argued that the notion of space is ‘counter-intuitive in a legal context … since the aspect of formal(ized) boundness that goes with territory is lacking’.Footnote 49 Moreover, such an approach is seen as ‘less pervasive when applied in the context of an inquiry into the nature of evolving legal norms, which grow out of border-crossing “privatized”, and transnational norm-making processes’.Footnote 50 Space then ‘ceases to demarcate an identifiable, confined realm’.Footnote 51 These critical views highlight some of the limitations of a territorial understanding of legal space, yet they leave a non-territorial understanding of this notion unaffected. Recognizing the limitation of the former, this article opts for the latter.

Third, it is crucial to move beyond using legal space in a merely intuitive manner and rather to thoroughly conceptualize this notion. Otherwise, it will not be able to truly overcome the above-mentioned limitations of the concept of legal order. However, scholars have often employed the notion intuitively – that is, without expanding on its defining features and analytical reference points.Footnote 52 Certain bodies of law are referred to as legal spaces, but it is not explained what characterizes them as legal space (including in comparison to a legal order). Although this intuitive use highlights the analytical appeal of a notion that does not claim that a body of law has the characteristics of a legal order – thus highlighting the need for an alternative to the notion of legal order – it can only be a first step. For legal space to have analytical value and to be a transparent and comparable notion in legal discourse, it is necessary to flesh out its defining features. Indeed, some authors have started to engage with the notion in more detail. However, so far this has been done in a way that does not explore the full potential of the notion as alternative or complement to the concept of legal order. Again, the notion of ‘European legal space’ is a good example. Although this notion can contribute to mitigating the order-focus of some of the European law literature, various crucial questions remain open. In particular, while the notion presupposes a ‘dense social interaction’ within the space,Footnote 53 it does not further conceptualize intertwinement and hybridity both within the space and with regard to external norms. It is not addressed how the European legal space relates to other legal spaces, both internal and external to it. Specifically, it remains unclear how permeable or impermeable the boundary of the legal space is supposed to be.

Other examples of how the notion of space is used show that what is theorized is mostly the qualifier that comes with the space rather than the space itself. This is the case for the qualifier ‘transnational’ in notions such as the ‘transnational legal space’, ‘transnational space’ or the regulatory space related to transnational law.Footnote 54 These notions are employed to encompass forms of legality that do not fit into the domestic/international binary.Footnote 55 They explicitly aim at overcoming a territorial understanding of space.Footnote 56 Yet, rather than providing a conceptual framework for analysing specific legal phenomena, they serve as a catch-all term for everything that is not captured by the classical notions of domestic and international legal order. As such, their function is auxiliary and limited in their capacity to theorize legalities more generally. Similarly, the notion of ‘global administrative space’ mainly aims at overcoming the distinction between domestic and interstate international law.Footnote 57 Here again, the element of space in global administrative space remains conceptually rather pale, due to the fact that the main focus of this suggestion is to reconceptualize the notion of law rather than the notion of legal order.

This brief overview shows that the concept of legal space needs to be developed further for it to provide a more fruitful analytical tool. In the next section, I suggest a possible way in which one can conceptualize this notion. I develop a topology-inspired notion of legal space that addresses the requirements of an alternative concept.

III. Developing a topological approach to legal space

In this section, I sketch out some basic features of a topology-inspired concept of legal space. The concept is inspired by topological thinking rather than being an exhaustive representation of all the aspects of the mathematical notion of topological space. The aim is to use the guiding ideas of topological thinking for assessing sets of legal elements. The article explores these possibilities.

To develop this approach, I first introduce the guiding ideas of topology that are relevant to the present context. On this basis, I construct the topological notion of legal space by specifying how topological insights can help to analyse the inner structure of the legal space, its boundaries and the interrelations among legal spaces.

Topology’s guiding ideas

At first glance, topology is a mathematical concept that seems far removed from legal theoretical discussions. As will be explained further below, it is a tool to analyse mathematical objects. Yet upon a closer look, topology provides many insights that can constitute a fruitful basis for conceptualizing legal phenomena. To link these insights to the notion of legal space, this section outlines relevant aspects of the mathematical notion to which the subsequent sections relate.

To start with, topology calls its analytical objects spaces (in line with the Greek origin of the term). Linking this approach to the notion of legal space thus does not seem unnatural from a terminological point of view. Further, topology aims at categorizing spaces, their elements and their interrelations. This corresponds to the aspirations of an alternative concept to the notion of legal order. A legal concept that provides such categorization makes it possible to conceptualize the various kinds of overlapping legalities and forms of intertwinement that are characteristic of an environment shaped by multiple legalities. Both in the mathematical and the legal context, the broad objectives are thus similar.

More specifically, a first important guiding idea of a topological approach relates to its way of analysing objects. It is qualitative rather than quantitative. Measuring the exact ‘geometrical’ dimensions of an analytical object such as length or angles is not necessary. Instead, the qualities of the object, its structure and the way its elements are linked determine the topologically relevant features of an object. Classical objects that share similar topological features include a sphere, a cube and a pyramid. While these objects differ in terms of their number of edges and potentially have different sizes, all of them are three-dimensional objects that are solid – in contrast to, for example, a doughnut-shaped object (or torus) that has a ‘hole’. Being solid or having a hole reflects topological properties that cause the first three objects to have the same topological structure, while the doughnut-shaped object has a different structure. Similarly, the letters D and O share the same topological structure – a ring-like shape – in contrast, for example, to the letters C and I, that are both composed of a line where the ends are not connected to form a ring. These illustrations show that the structure of these objects matters, rather than their size or exact shape. This approach allows us to compare analytical objects based on considerations that – although they might be less intuitive than a quantitative perspective – focus on similarities rather than differences between objects. It makes it ‘possible to identify several forms that do not have the same appearance or the same dimensions with the same object’Footnote 58 and to reassess ‘principles of likeness and unlikeness’.Footnote 59 When studying legal spaces, such a fresh perspective on what should constitute the decisive analytical categories and features for comparison is useful. Moreover, moving away from ‘measuring’ makes it easier to construct a notion of legal space that is not tied to determinable territories.

For topology, the defining features of the space are the interrelations of its elements and the resulting structure within the space. A topological space is a set of elements endowed with a topological structure.Footnote 60 For the legal context, this way of defining the space allows us to combine the two aspects of (1) defining spaces and (2) conceptualizing interrelations of their elements. This speaks to one of the requirements of an alternative concept presented above. As the following section shows, such an understanding of space makes it possible to capture both the nature of legalities as well as their overlaps and intertwinement.

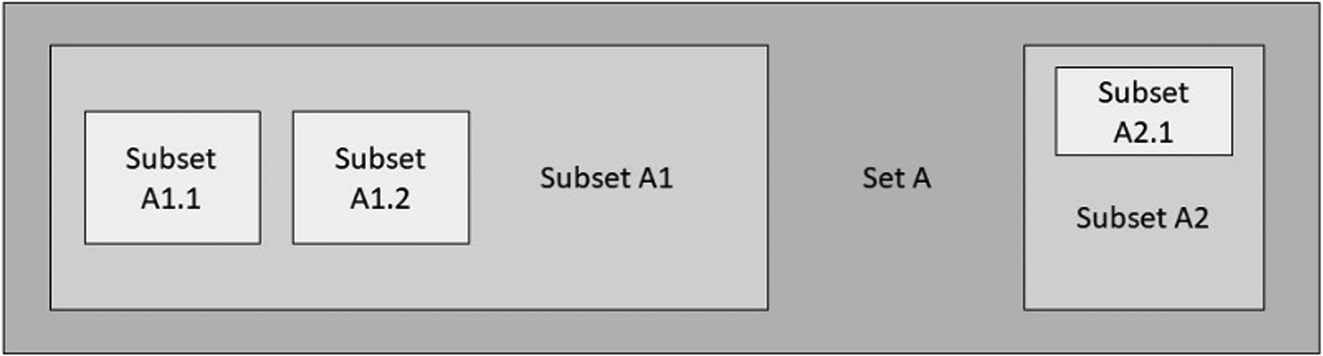

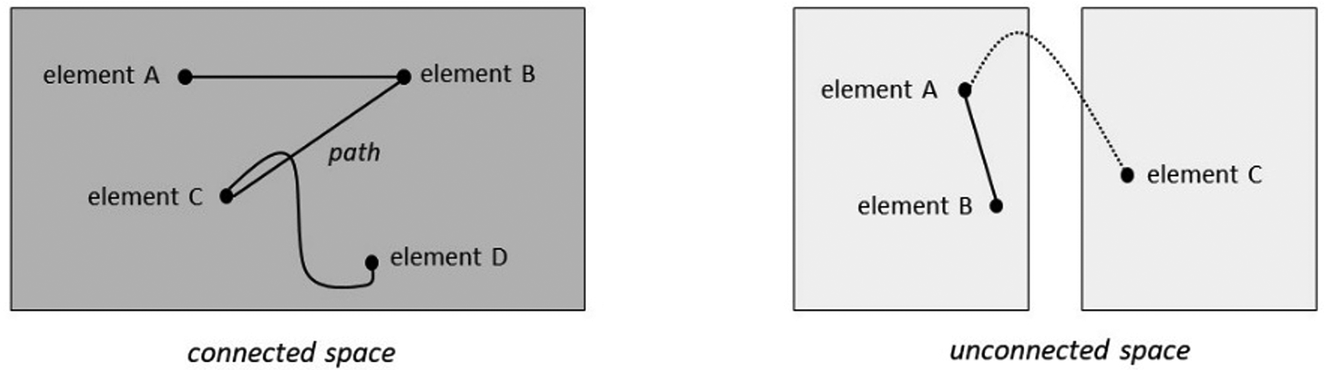

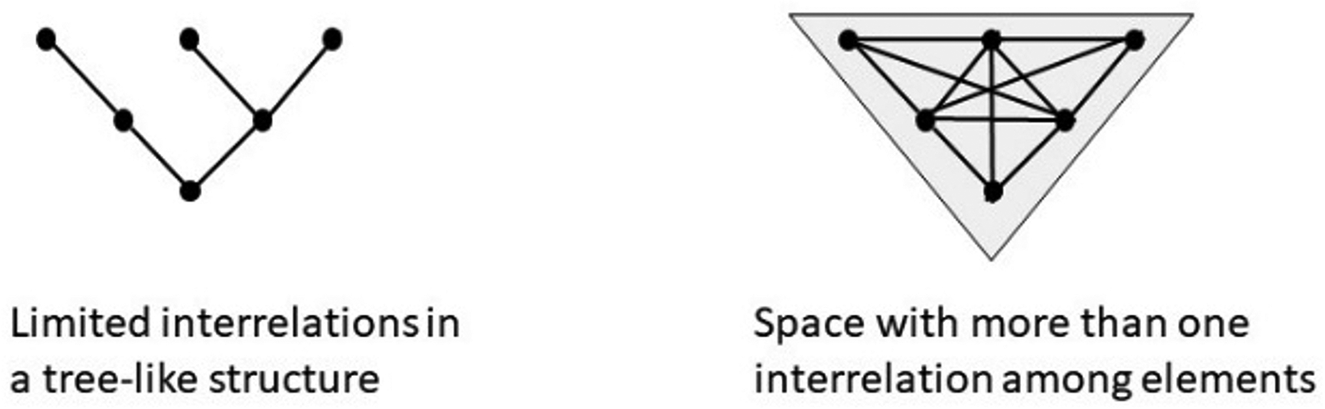

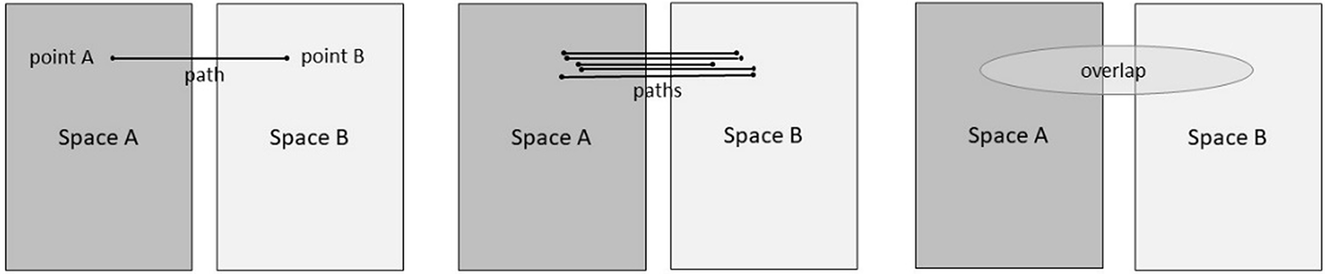

To conceptualize the interrelations among the elements belonging to a space and the resulting structure, topology offers various analytical tools. First, topology groups such elements into sets and subsets. In this way, an inner structure of the space can be spelled out (an example is provided in Figure 1). Second, the connectedness of sets and spaces is a principal topological feature. In a connected space, the elements of the space can be linked to each other by a path that does not cross a boundary.Footnote 61 If it is not possible to connect the elements by a path that stays entirely within the space, the space is unconnected (Figure 2). Third, from a topological perspective, interrelations among elements are not limited to tree-like structures which only allow one interrelation between elements. But it is possible to consider a plurality of interrelations among many different elements at the same time (Figure 3). Consequently, spaces can have more or less connecting paths among their elements. As the following section outlines, these analytical tools can be used in a fruitful manner in the legal context.

Figure 1 Representation of sets and subsets

Figure 2 Examples for connected and unconnected spaces

Figure 3 Comparison of the limited interrelations in a tree-like structure and a space with various interrelations among its elements

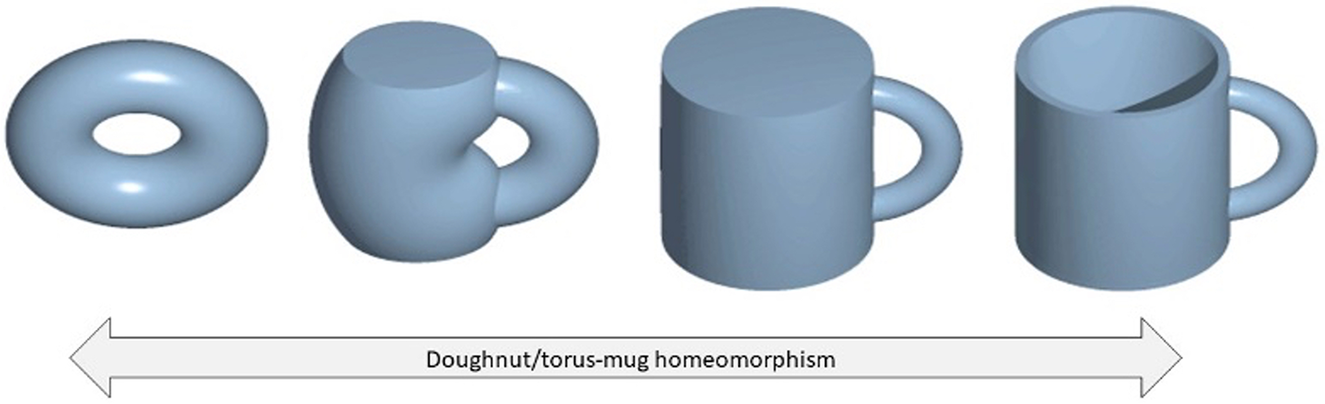

A further guiding idea of topology is a dynamic perception of objects. Without being limited to assessing the state of an analytical object at a given point in time and with a given shape, a topological approach allows for transformations. There is continuity between analytical objects when they change without losing their topological features – and thus without losing their identity.Footnote 62 A key topological notion for this is homeomorphism. Even if an object is transformed by being stretched or bent, but without being ruptured or cut, it maintains its properties.Footnote 63 For example, a circle can be converted into a square and vice versa; a coffee mug-shaped object can be transformed into a doughnut-shaped object and vice versa – a well-known topological example (see Figure 4); and the elements of a set can be rearranged without changing the structure of the set (see Figure 5).Footnote 64 More generally, this dynamic perception makes it possible to distinguish between change that affects the identity of a space and change that does not. For example in Figure 4, ‘the essential permanent feature is the hole in the [doughnut], which continues unchanged, even when shifted to the handle outside of the mug, meanwhile preserving the essential continuity of all else in the object’.Footnote 65 For law as a dynamic analytical object that fluctuates continuously, an inherently dynamic concept such as topology is well suited. While considering this inherent dynamic, it also allows us to conceptualize structural change – that is, when a space changes its features.

Figure 4 Homeomorphic transformation of a doughnut-shaped object into a mug-shaped object and vice-versa

Figure 5 Representation of homeomorphic spaces with sets and subsets

Beyond the inner structure of a space, topology addresses the way its elements relate to the outside, to their surroundings. This includes two elements: the boundaries of a space and potential overlaps between spaces. Regarding the boundaries, topology considers both spaces that have a boundary and spaces that do not have a boundary. The latter are defined by a point of reference and its surroundings. This shows that boundaries are an optional, but not necessary, element of the space – it is not a defining feature. Further, for spaces that do have boundaries, topology distinguishes between whether or not these boundaries are a part of the space itself. The space is topologically open if it contains none of its boundary points and closed if it contains all of its boundary points (Figure 6).Footnote 66 As I outline below, these features of boundaries are relevant when assessing sets of legal elements in the context of multiple legalities.

Figure 6 Differentiation between topologically open and closed spaces

The second tool that helps to capture how a space relates to its surroundings concerns overlaps between spaces. By grouping elements into sets and subsets, a topological approach illustrates whether certain elements belong to two or more sets or subsets at the same time. Elements that constitute an overlap between sets are thus hybrid in nature (Figure 7). They belong to more than one set at once. These hybrid elements constitute the intersection among the overlapping spaces – that is, the set that contains all elements that belong to both spaces concerned (but no other elements). Overlaps can also be part of a dynamic movement of sets between a disjoint and an overlapping stage.Footnote 67 Below, I show how such dynamics can be spelled out for the legal context, especially when assessing how various spheres of legal ordering can be intertwined.

Figure 7 Representation of an intersection between spaces

Constructing a topological understanding of legal space

After this brief overview of some of the basic ideas of topology that can be fruitful for analysing multiple legalities, I expand on these considerations and relate them to the notion of legal space. I propose a possible way in which a topological perspective can contribute to constructing a concept of legal space that is able to generate novel analytical insights. I consider such insights for the inner structure of legal spaces, the boundaries of these spaces and the interrelations with other spaces.

Inner structure of the legal space

As will be outlined in this section, a topology-inspired notion of legal space is defined by the interrelations of its elements and the resulting structure within the space. This way of defining legal space speaks to the call for a more ‘central role of interactions across different sites and layers of law’.Footnote 68 Making interrelations the key defining feature also relates to the communicative thrust of interactional accounts of lawFootnote 69 as well as a network analysis of legal actors, yet without focusing exclusively on the behaviour and perceptions of actors.Footnote 70

For it to be a legal space, the relevant elements must be of a legal nature. By way of example, such elements might include formal and informal legal norms, judicial decisions and other communicative acts of public, private or hybrid legal actors. However, the notion of legal space does not predefine what qualifies as legal. It is an analytical tool that leaves room for various understandings of the law and legal nature. The notion does not prescribe in an abstract manner ‘where to draw a line between legal and non-legal’.Footnote 71 Rather, it is for the users of this notion of legal space to decide how and whether to delimitate that which should be considered legal in nature.Footnote 72 For example, the notion of legal space can be used both by a formally oriented approach, which would link this quality to institutions and procedure, and by an actor-centred approach of law that would rather focus on the practical behaviour of actors. A legal space can also capture forms of legality that do not fit into a state-centred understanding of law. Moreover, it allows combining various approaches – for example, conceptualizing at the same time the relationship of norms and of actors, rather than only focusing on one kind of legal element.Footnote 73 The term ‘legal’ in legal space is thus conceptually open. As an analytical tool, its emphasis lies on the term ‘space’.

The above way of defining a legal space is inclusive and flexible. It allows for many different sets of legal elements to be considered as legal space. This is in line with the general topological approach that the ‘concept of space is considered to be as general as possible’.Footnote 74 It also shows that the notion of legal space has a fluid ontological purpose: when using this notion, the analysing actors decide upon which set of legal interactions to focus. In this way, the notion of legal space can be used in a broader variety of analytical settings than the notion of legal order.

Specifically, the notion of legal space does not require certain aspects that are part of the notion of legal order. First, a legal space does not require any institutional structure on which the interrelation of its elements would be based. Linking the elements in a legal space to a specific norm-creating entity is possible but not necessary. One can use the notion in an institution- and actor-independent manner. Second, it is not required that the relevant legal actors recognize certain norms as part of a specific legal space in the sense of, for example, a rule of recognition. Actors and their behaviour play a role as relevant elements of the space and for assessing communicative paths among these elements. Yet whether one considers a set of elements to form a legal space does not depend on the perception of these actors. Third, the notion does not require the reference to a territorial framework in which the interaction takes place. It does not have a territorial dimension – territory or geometrical space is not part of the concept. Fourth, the notion of legal space does not require or claim coherence among the elements of the space. The inner structure of the space is analysed according to other categories.

Instead of focusing on the above requirements of a legal order, a topological perspective provides several insights in the inner structure of the legal space. To start with, the defining feature of the legal space are the interrelations of its elements. For a plurality of objects to constitute a legal space, there must be an interaction among these objects. These interactions occur along communicative paths among elements. The possibility for the elements of the space to interact along such paths without crossing a boundary of the space constitutes the space’s connectedness. In a legal space, elements can communicate along paths in a broad range of ways. For example, communication occurs when one norm is interpreted in the light of another norm; when judicial decisions refer to other decisions; when new norms are developed based on existing principles; when norms require or enable the creation of other norms.Footnote 75 From the perspective of legal actors, interrelations are created when actors use norms (of any kind) and entwine these norms through discursive use into a body of law, forming a legal space. The most salient examples of the varying communicative paths among the elements of legal spaces are provided by non-formalized legal spaces such as global administrative law. This legal space is constituted by a range of communicative paths, including the cross-referencing of decisions by administrative tribunals of various international organisations; administrative rules being interpreted with reference to common principles of access to justice, transparency or accountability; or the use of domestic notions to fill gaps in international legal frameworks.

A topological approach allows each element of the space to have a broad range of interrelations with the other elements of the same space (see Figure 3 above). The elements are thus not limited to interrelations along tree-like structures, which would only allow for very few interrelations per element as tree-like structures only allow one path between elements. It thus differs from conceptualizations of the legal order that have a ‘Stufenbau’ or similar hierarchical structures at their core.Footnote 76 Such models consider interrelations in a way that corresponds to tree-like structures. Instead, the interrelations within the legal space are numerous. An element can be linked to another element by more than one path. It can be linked directly and/or via intermediate elements. An example of the latter is two rules being interpreted in light of the same principle: there is a communicative path from the first rule via the principle to the second rule. Representing such interrelations as a topology with manifold paths allows us to capture the heterarchical nature of many legal interrelations. Further, it illustrates that interrelations among legal elements are flexible rather than static: the interrelating paths among elements can vary while preserving the connection.

Moreoever, one can complement this topological understanding of the interrelations of the elements within a space with the notion of density, a concept stemming from graph theory (a mathematical branch related to topology) that can provide additional insights into the inner structure of a legal space.Footnote 77 Understood in this sense, the density of a space varies depending on how many of its elements are connected with each other. Density is a way to express the proportion of existing interrelations among elements within the space compared with the potential interrelations that would be possible among these elements. The closer to the maximum number of possible links, the denser the space.Footnote 78 For some sets of legal elements, the interrelations among these elements will create a denser structure than for others, a fact that is empirically assessable.Footnote 79 For example, for certain legal spaces that are classically regarded as legal orders, such as domestic law or EU law, the density might be higher – at least in parts – than for other sets of legal elements such as global administrative law.Footnote 80

A further way to analyse the internal structure of a legal space from a topological perspective is as sets and subsets of the legal elements that constitute the space (see Figure 1 above). A feature of the legal space is that its elements can be described in such terms. Sets and subsets can relate to classical categorisations such as a functional groupings of legal elements and groupings according to the formal origin of a norm or the nature of the actors involved. In a legal space such as environmental law or human rights law, subsets might include legal norms of a domestic or international origin; norms aimed at, or created by, private, public or hybrid actors; procedural and substantive norms; issue-specific categories such as economic, social, cultural, civil and political rights, and so on. Similarly, the elements in novel legal spaces such as Facebook’s platform law can be grouped into subsets of an international origin, such as international human rights law; of an internal origin, such as platform standards; and of a domestic origin, such as the trust law providing the legal framework for the Facebook Oversight Board. However, aside from these examples, sets and subsets are an analytically open notion and can also be constructed based on other criteria or combinations thereof. What is important is that, conceptually, the inside of a space does not necessarily appear unordered. Subsets can create an internal order of the elements concerned, including by containing further subsets. This can lead to a multi-level ordering structure within the space. Further, subsets can overlap, be joint or disjoint, or be closed or open – notions that are discussed in more detail below.

Together, sets/subsets and the communicative paths that create connectedness (see above) thus provide complementary analytical tools allowing to conceptualize the interrelations of legal elements within the space. These complementary analytical lenses illustrate and capture the coexistence of ‘order and disorder’ of law.Footnote 81 While communicative paths can create apparently messy structures, and are thus an analytical lens to engage with the ‘disorder’ of law, sets/subsets provide an ordering dimension that adds a different perspective on the former.

An additional aspect of a topology-inspired concept of legal space relates to the question of change. As long as the inner structure of the space maintains its features, a changing shape of the space does not affect the space’s identity. In the sense of homeomorphism, a space that is merely growing, shrinking or bending remains topologically identical. Only if the features of the space change as well – for example, with regard to its connectedness, its subsets or its boundary characteristics (see below) – will the identity of the space be altered. This is a fruitful distinction for assessing developments in law. It allows to qualify structural changes, changes from one ‘type’ of legal space to another. For example, in relation to the scholarly discussion of whether the current challenges faced by international law will lead to a different ‘type’ of international law,Footnote 82 a topological perspective suggests the following differentiation: if we were to witness a shrinking of some parts of the classical international legal space with less cooperation among states, this by itself would not have any structural impact on the space. It would remain topologically identical. A (sectoral) reversal – or, for that matter, its initial occurrence – of the ‘juridification’ of international relations during the 1990s – that is, the then notably growing body of international regulation – does thus not qualify in itself as topologically relevant shift. In contrast, if (also) features such as international law’s connectedness – subsets among the elements of the space or boundary characteristics – change, then a new topological ‘type’ of legal space might emerge. Similarly, if a legal space such as EU law or the law of other regional integration organisations expands over time, the mere expansion would not alter its topological features. Only if these features were to change – for example, with regard to boundary elements or overlaps with other legal spaces such as domestic law or regional human rights law – would this constitute a topologically relevant modification. Further, it is possible to use the lens of homeomorphism to assess legal changes such as those triggered by digitalization. While the impact of artificial intelligence and automatized decision-making may seem as a structural shift – for example, for tort law or administrative law – one might consider such legal spaces to merely ‘bend’ in a homeomorphic sense when their existing rules are being adapted to construct liability for self-driving cars or accountability for discriminating effects in automatized administrative or judicial decision-making.Footnote 83 The concept of homeomorphism can thus be a fruitful reference point for assessing a broad variety of legal developments. In addition, it can be used as lens for a comparative analysis of legal spaces. When the topological features of two legal spaces are equivalent, they can be considered homeomorphic in nature. Structural identity of – at first sight dissimilar – legal spaces can be highlighted in this way.

The notion of legal space as suggested here thus provides a novel perspective on the inner structure of legal spaces, allowing for a comparison of legal spaces and their features that captures structural similarities and differences that other perspectives might not consider. In the context of multiple legalities, this also constitutes a basis for understanding the interrelations among different legal spaces (see below).

Boundaries of the legal space

A second reference point for assessing legal spaces is their boundaries. In topological terms, boundaries are composed of elements that neighbour elements both from within the space and from the outside.Footnote 84 Boundaries can determine certain topological features of the space.

Particularly relevant for conceptualizing legal spaces is the differentiation between spaces that are open or closed in the topological sense. As mentioned above, a space is topologically closed when its boundaries are part of the space – that is, when the elements that constitute the boundary belong to the space. Accordingly, a space is topologically open when the boundary elements are not part of the space (see Figure 6 above).

For the context of law, the distinction between open and closed spaces corresponds to the question of whether a legal space determines its boundaries itself with boundary elements that belong to the space in question, or whether these boundaries are composed of external elements formed by norms or actors that are not part of the legal space. Two aspects are relevant in this regard: whether a legal space itself specifies which elements are part of the space (as, for example, constitutional provisions do); and whether a legal space regulates itself whether and which legal elements stemming from other legal spaces can cross its boundaries. In contrast, the terms ‘open’ and ‘closed’ do not describe the extent to which interrelations among legal spaces in the sense of communications and overlaps exist (see more on this aspect below).

The boundaries of legal spaces are thus constituted by two components: definition elements and permeability elements. Definition elements aim at a self-definition of the legal space. Certain legal spaces consider themselves to form an entity and thus define (from their internal perspective) which elements belong to this space. Defining elements might include so-called secondary rules such as procedural provisions defining law-making within this space, and norms that set certain substantive values as yardstick for valid law within this space. It might also include shared understandings by the actors that shape the discursive interactions within the space as to what defines the specific legal space. Legal spaces such as EU law, WTO law or domestic law could be said to define their own boundaries, and thus to be topologically closed. For domestic and EU law, the constitutional provisions of each legal space define the circumstances under which legal elements are considered part of these spaces. For WTO law, its treaty-basis delineates its boundaries. In contrast, one could argue that human rights law constitutes a – functional – space that does not (or does not fully) define its boundary and, in this regard, is topologically open. What is considered part of human rights law is a conceptual question that the legal norms as such do not address themselves and on which actors might disagree (for example, as to what human rights are or whether regulation by private actors is included). The defining elements of this legal space are not part of the space itself. Similarly, diverse bodies of law such as global administrative law, corporate social responsibility law or the lex sportiva used by the Court of Arbitration for Sport would arguably qualify as topologically open spaces, as their elements also do not determine themselves the boundaries of the space. These examples show that a legal space can exist without defining elements. Such a notion of legal space contrasts with an understanding of legal order that would require secondary rules to determine its boundary.Footnote 85

The second set of elements that can constitute the boundary of a legal space – again without being a necessary requirement of the space – comprises permeability elements. Classical permeability elements might include reception norms that determine the conditions under which external legal elements can interrelate with the internal elements of the space.Footnote 86 One could, for example, consider classical private international law – that is, the elements of domestic law that regulate its relationship towards other domestic law – as boundary elements of the domestic legal space. As these elements belong to the space itself, the domestic legal space would be topologically closed. The domestic space itself determines the permeability aspect of its boundary. In contrast, when (a part of) domestic private international law is harmonized by EU law, as is the case with the Rome I and II regulations or the Brussels regulation, one could understand this as boundary elements being removed from the domestic legal space. These boundary elements are then part of the EU legal space. Such a development would constitute a shift from each domestic legal space of the EU member states being closed in the context of private international law to being (in part) topologically open. This example shows not only that the quality of a legal space as open or closed can change, but also that legal spaces can be partially open or closed depending on the regulatory area in question.

In addition to providing a feature for describing different spaces, the boundary characteristics can contribute to conceptualizing issues pertaining to the interrelations between spaces. Figure 8 highlights this aspect: the boundary between spaces can belong to either one of the spaces; it can be part of neither of them; and it can be part of both. It is, for example, possible to frame the different perspectives of EU law and domestic law regarding their relationship as a boundary issue. According to EU law, the boundary between EU and domestic law is composed by legal elements that belong to the EU legal space. From an EU law perspective, the EU legal space defines itself the extent to which it reaches (competence norms), as well as its relationship to domestic law (primacy, direct effect). From this perspective, the EU legal space is a topologically closed space. It considers itself to be ‘Space A’ in the second image shown in Figure 8. In contrast, from the perspective of the law of many member states, the EU legal space is topologically open. Its boundary is not (or not entirely) defined by EU law itself, but rather by domestic law. Provisions of domestic constitutional law as to the transfer of competence and notions such as constitutional identity aim at establishing a domestically defined boundary of the EU legal space. From this perspective, EU law is ‘Space B’ in this image, while domestic law is ‘Space A’. Accordingly, one could consider the dispute between the CJEU and some domestic constitutional courts regarding who is the ‘final arbiter’ as being a dispute about the boundary of the EU legal space - that is, about whether this space is topologically open or closed. A similar framing, including with regard to shifts in the topological relevant features, is possible for contexts such the inter-American human rights protection system. When the conventionality control instrument was created by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights,Footnote 87 this could be understood as a regional human rights space aiming at defining the elements of the space’s boundary with domestic law. From this perspective, this legal space has turned to consider itself topologically closed – while, here again, domestic law would understand the space as open. For both examples, if one moves beyond the individual perspectives of the legal spaces concerned, one can conceptualize the boundary between them as belonging to both – as represented in the third image of Figure 8.Footnote 88 This means considering the boundary to be hybrid in nature.

Figure 8 Variations in boundaries between spaces

More broadly, one can understand the issue of how to resolve conflicts between norms stemming from different legal spaces as an aspect of topological boundaries. When solving such conflicts, one needs to decide which of the concerned legal spaces determines or should determine the standards for conflict resolution. Is it one of the legal spaces, and if so which? Or should the standards be determined by both legal spaces – for example, in the form of common principles? This issue can be conceptualized as discussion about whether the boundaries between the relevant legal spaces belong to one of the legal spaces or whether they are shared by both – in other words, whether the boundary is constituted by hybrid elements belonging to both spaces (Figure 8). In the legal pluralist debate, this is both an empirical and a normative question that has received some attention. Those who argue for a unilateral approach to conflict resolution (for example, on a conflict of laws basis), argue for topological boundaries that are not shared.Footnote 89 They can point to many examples, especially in domestic law where such an approach is taken in practice. Based on such an understanding, each legal space determines its boundaries towards the other legal spaces. Each legal space is thus considered topologically closed. In comparison, others suggest shared boundaries, with hybrid boundary elements belonging to both legal spaces concerned. It is seen as normatively desirable to overcome unilateralism by taking a ‘composite perspective’.Footnote 90 Hybrid boundary elements have been proposed for the interrelations of various legal spaces, specifically under the heading of constitutional pluralism.Footnote 91 Suggested hybrid boundary elements include guiding principles such as the principle of legality, the level of human rights protection or democratic representation. These discussions can thus be represented in topological terms.

In addition to the distinction between open and closed boundaries, boundaries can also be analysed in terms of their degree of resistance.Footnote 92 Although this aspect stems from a sociological application of topology rather than strictly representing the mathematical concept of topology, it can nonetheless offer an additional feature of legal space as a legal concept. The degree of resistance describes to which extent interrelations between an element of the legal space and elements of the space’s surroundings are restricted by the boundary. This aspect is thus not about who determines boundaries, but rather about their effect on cross-boundary communication among legal elements from within and outside the legal space. Such communication can be easier when the degree of resistance is rather low and more difficult when the degree of resistance is rather high. The degree of resistance can, in principle, be at the maximum, which would make any crossing of the boundary impossible. A maximum degree of resistance would amount to a legal space that is completely sealed off from its surroundings – it excludes any influence of, or communication with, external elements. Such a legal space is, at least in the present legal landscape, difficult to imagine. In contrast, a lower degree of resistance creates permeability. It is the precondition of any cross-boundary communication. The permeability elements mentioned above determine the degree of resistance. They can establish that, under certain conditions, external elements cannot interact with internal elements. Examples include the private international law notion of ordre public, the Solange-jurisprudence of courts such as domestic constitutional and European courts based on an equivalent protection testFootnote 93 or a shared understanding that a body of law constitutes a lex specialis vis-à-vis other norms.Footnote 94 For a broader assessment, the number, nature and quality of communicative paths between elements belonging to a specific space and elements from this space’s surroundings can provide an indicator of a space’s degree of resistance by which a boundary is characterized.

In sum, the above-mentioned characteristics of boundaries highlight that a topology-inspired concept of legal space provides us with categories for boundaries that allow for a comparison rather than postulating a single approach, as concepts of legal order often do. Legal spaces can be topologically open or closed, and have more or less resistant boundaries – without their nature as a legal space being affected. This notion of legal space is thus not only more inclusive and flexible than other more limited concepts; it also provides analytical tools that can capture differences in legal spaces and their interrelations.

Interrelations among legal spaces

A topological approach is particularly well suited to conceptualize the interrelations among legal spaces. As outlined above, assessing the topological boundaries of the space is one of the aspects that helps us understand the interrelations among legal spaces. But beyond boundaries, various further features can contribute to capture the variations of these interrelations.

First, legal spaces can relate to each other in such a way that one is a subset of the other (set A and subset A1), or they can form separate spaces that are foreign to each other (set A and set B). This corresponds to the classical question of whether two bodies of law form a unity or a plurality – one of the aspects discussed by monist, dualist and pluralist approaches. The topological terminology of sets and subsets allows to represent this binary relational characteristic (unity or plurality), yet without being limited to it.

Second, a topological approach addresses the question of whether legal spaces are separate in the sense of fully autonomous entities or are intertwined. A key notion to represent intertwinement among spaces is the overlap. When legal spaces overlap, the elements of the intersection are part of each of the overlapping spaces.Footnote 95 These legal elements are thus hybrid in nature. Inversely, if one can determine hybrid elements, this indicates that there is an overlap between the spaces concerned. As I have discussed elsewhere, processes that can result in hybrid legal norms include the cross-border implementation of norms, the generation of general principles of law and consistent interpretation of norms of one legal space in conformity with the norms of another legal space.Footnote 96 Overlaps are thus a way to capture ‘travelling’ content of legal norms that constitutes normative interaction among spaces. Such overlaps can be formally enshrined in the legal norms, but also discursively constructed. Actors can ‘make claims about the relation of norms from different backgrounds, and they thus define and redefine the … interconnection between the norms at play’.Footnote 97

The resulting hybrid legal elements are a full part of each legal space without affecting the boundaries of the space. From a topological point of view, overlaps thus do not ‘blur’ the boundaries of the space or create an ambiguous ‘twilight zone’ among them, as some of the legal pluralist literature would have it;Footnote 98 rather, they represent intersections – in other words, hybrid zones – among legal spaces.Footnote 99 These intersections can be clearly defined.

Understanding overlaps as intersections between sets of legal elements also illustrates that, in general, overlaps only concern certain ‘clusters’ or subsets of legal elements of a space, rather than the whole space. Otherwise, the space would be a subset of another space. This corresponds to the observation that ‘law sometimes, or even oftentimes, appears in both the singular and the plural, as both one and many’.Footnote 100 For a topological notion of legal space, it is not necessary to measure the exact dimensions of an overlap that does not encompass the whole space. As long as the overlap is partial, it makes no structural difference whether the overlap is smaller or bigger.

Furthermore, overlaps can occur among sets and among subsets. For the interrelation of legal spaces, that means it is possible to assess such overlaps independently of the above question of whether two bodies of law form a unity or a plurality. For example, for analysing overlaps between EU law and general international law, it is not necessary to determine whether or not the EU legal space and the space formed by general international law are subsets of a broader space.

Structural differences among overlaps can relate to the connectedness of the intersection created by the overlap. Spaces can overlap in a way that all the elements of the intersection can be connected without crossing a boundary; alternatively, they can create an intersection that consists of unconnected sets. Figure 9 provides examples of a connected intersection (AB) and a disconnected intersection (CD).

Figure 9 Examples of connected and unconnected intersections

These structurally different overlaps can be used to conceptualize interrelations of legal spaces. Intuitively, many overlaps seem to lead to a single connected intersection between two legal spaces. However, an example of an overlap that creates an unconnected intersection might be provided by the law of international organisations (IOs). When IOs create their own substantive law, the substantive part of the IO legal space can overlap with other legal spaces such as a domestic legal space. At the same time, the institutional law that is part of the IO legal space can also overlap with the same domestic space. This might include questions such as immunities, legal personality or host state agreements. The intersection between both legal spaces would then be composed of one substantive law set and an institutional law set, which in their nature as intersection are unconnected. Put differently, the interrelation of domestic law with each ‘branch’ of the IO legal space is independent of the other. This corresponds to the overlap of spaces C and D in Figure 9.

Third, for spaces that do not overlap, another relational variation can become relevant. Interrelations between spaces can be characterized by whether and to what extent spaces are joint (independently of whether they are topologically open or closed). Spaces can be fully disjoint from one another; they can meet by partly bordering on each other; and one space can fully border the other space in the sense of one space fully enclosing the other (Figure 10).Footnote 101 In the latter scenario, spaces E and F are complements in the set composed by E and F so that each of the elements of this set must belong either to E or to F.

Figure 10 Representation of joint and disjoint spaces

For legal spaces, the difference between joint (or meeting) and disjoint spaces is relevant in several ways. It determines whether and to what extent the spaces have a common boundary. If they do, the variations outlined above become relevant: whether the boundary elements belong to one of the spaces, to both or to none. Further, differentiating between joint and disjoint spaces can represent how likely it is for legal spaces to communicate with each other. For joint spaces, communication might be expected to occur more often.

Moreover, the variation of fully joint spaces in Figure 10 merits a closer look. Spaces E and F are complements. Thus, space E cannot expand without affecting space F and space F cannot expand its inner boundary without affecting space E. This is not the case for disjoint or partly joint spaces, which are not limited in this way by the existence of the other space. A legal scenario that corresponds to the relationship between spaces E and F might exist in situations in which the relationship between legal spaces is characterized by a division of competences. For example, in the case of shared competences of the EU vis-à-vis the competences of the member states, the exercise of legal norms belonging to one legal space (EU law) delimits the shape of the other legal space (domestic law). The EU legal space has a limiting effect on the elements of the domestic legal space. Inversely, based on the principle of conferral, competences can be shifted from the domestic to the EU realm so that the shape of the EU legal space is altered when domestic law changes in this respect. In contrast, the situation is different when legal spaces are merely co-regulating a subject matter. Co-regulation might create overlaps, but it does not limit the legal spaces in the same manner.

Fourth, a further topology-inspired categorization that can provide insights for the interrelation of legal spaces is to distinguish between various ways of communication among legal spaces. Such communication can take place by one-dimensional paths that connect an element of one legal space and an element of another legal space by crossing the boundary or boundaries between the two spaces. Such paths do not correspond to overlaps. As outlined above, overlaps exist when some elements of one legal space are also elements of the other space, thus constituting hybrid elements. This is not the case for communication by paths. The communicating elements remain attributed to only one of the spaces. Such paths do not extend or alter the spaces concerned. Specifically, they do not create per se overlaps between spaces. Examples of path communication might include courts of one legal space occasionally cross-referencing the decisions of a court belonging to another legal space or the occasional migration of constitutional concepts from one domestic legal space to the other. Discursive interaction among judicial actors often is the most visible expression of path communication among legal spaces,Footnote 102 but other actors of various nature – such as institutional actors,Footnote 103 informal regulators, litigants and other addressees of law – can create such interactions as well. For example, in the area of data protection law, path communication among various actors occurs when the EU regulation is used both as an inspiration by legislators in other states and as a reference point for the behaviour of private actors engaging in trade with, or providing services to, actors in the EU. More generally, open legal concepts that are used in some form in various legal spaces provide communicative reference points – for example, when actors construct notions such as good faith, due diligence or fair trial.Footnote 104 For path communication, the relevant actors play a decisive role. While formally enshrined path communication can exist, the actor-shaped ‘social practice is a constant bridging’ between legal spaces.Footnote 105

The differentiation between overlaps and communicative paths can be useful to qualify different forms of interaction and highlight their varying structural impact. It illustrates variations in the degree of intertwinement, which does not always have the same intensity and might not always lead to overlaps. Moreover, considering both communicative paths and overlaps also allows us to consider shifts between both ways of communication. If a significant number of communications by one-dimensional paths occurs, and these paths are similar, this can amount to constituting an overlap. Path communication can thus create a more substantial interaction between the legal spaces concerned. Figure 11 illustrates these scenarios of communication between spaces. Legal spaces that at one point in time only communicate by paths can, if this communication intensifies, create an overlap. One could argue that the recently intensified communication between human rights law and climate change law could represent such a shift. Inversely, it is possible for overlaps to dissolve and to be replace by mere path communication. Brexit might be an example for that. The representation in fig. 11 can thus provide a model for dynamic developments in the interaction among legal spaces including both ‘expansion’ and ‘contraction’.Footnote 106 This is crucial for understanding the interrelations among legal spaces: interrelations are ‘a highly dynamic process because the different legal spaces are non-synchronic and thus result in uneven and unstable mixings of legal codes’.Footnote 107

Figure 11 Shift from individual path communication to overlap

In sum, a topology-inspired approach provides various tools to conceptualize the interrelation of legal spaces both for a dynamic assessment and for snapshots of specific moments in time. It provides analytical tools to express the various dimensions that characterize the interrelations of legal spaces. And it makes it possible to compare different manifestations of intertwinement between legal spaces.

IV. Conclusion: Benefits of a topological understanding of legal space

From the above outline of a topology-inspired notion of legal space, three main benefits of this approach are apparent.

First, we gain a novel perspective on legal spaces and their interrelations. In the way that topology has gone beyond the quantitative analysis of geometry by offering a qualitative approach to spaces, a topology-inspired notion of legal space allows us to consider and highlight features of analytical objects that otherwise would go unnoticed or remain under-theorized. This concerns features of structural importance, permitting a comparative assessment of analytical objects that from a narrow quantitative perspective seem different in nature. For the increasingly diverse legal landscape, closely considering the relevant structural features is crucial to moving beyond certain reductive binaries that only go so far towards understanding and representing varying legalities. Such binaries include the legal order and the other, state-related law and the other, and formally binding law and the other.

This shift in perspective and the high level of abstraction at which it takes place necessarily mean that some features of law, such as a potential territorial grounding of some legalities, will not be represented in this concept. Yet, as with all forms of representation, depicting all features to the same extent is not possible. As de Sousa Santos observes:

We cannot get the same degree of accuracy in the representation of all the different features and whatever we do to increase the accuracy in the representation of one given feature will increase the distortion in the representation of some other feature.Footnote 108

The representation of structural features that we gain from a topological understanding of legal space is worth this compromise. Focusing on the interrelations of legal elements as one does when using legal space as an analytical framework allows for an in-depth assessment of legality and interlegality that cannot be achieved when using conventional theoretical tools. What is more, a topological analysis pushes to inquire which characteristics of bodies of law really matter. It creates an incentive to consider the representation of which characteristics is analytically the most useful to capture the current legal landscape. And it leads us to reflect normatively on which characteristics should determine whether a body of law is considered as an analytical object and how interrelations of legal elements are addressed.

A second benefit of a topology-inspired notion of legal space is that it allows us to capture more legal phenomena than other, rather restrictive notions do. Legal space can be used to address classical analytical entities such as domestic law and international law, but also more recent and conceptually challenging phenomena such as platform law and corporate social responsibility law. This is possible because it does not come with the normative baggage of other notions – including both the concept of legal order and more restrictive notions of legal space. The limiting assumptions that constitute this baggage are questioned. In this regard, the notion of legal space suggested here overcomes, on a terminological level, the tensions between a state-related, territory-based, public actor-focused, coherence-focused understanding of law and a pluralist, post-national, actor-inclusive, hybridity-considering understanding of law. This is because the notion of legal space has, as already mentioned, a fluid ontological purpose: the users of this notion can define which set of interrelated legal elements to consider as legal space for the assessment at hand. Considering a set of legal elements as legal space thus does not come with claims such as autonomy or coherence. Yet at the same time the legal space is not a mere metaphor, as it asserts an interconnectedness of its elements and an ability to be categorized in topological notions.