Abstract

Background

Appropriate quantification of exertional intensity remains elusive.

Objective

To compare, in a large and heterogeneous cohort of healthy females and males, the commonly used intensity classification system (i.e., light, moderate, vigorous, near-maximal) based on fixed ranges of metabolic equivalents (METs) to an individualized schema based on the exercise intensity domains (i.e., moderate, heavy, severe).

Methods

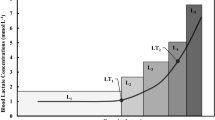

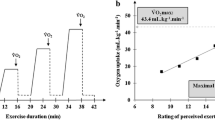

A heterogenous sample of 565 individuals (females 165; males 400; age range 18–83 years old) were included in the study. Individuals performed a ramp-incremental exercise test from which gas exchange threshold (GET), respiratory compensation point (RCP) and maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max) were determined to build the exercise intensity domain schema (moderate = METs ≤ GET; heavy = METs > GET but ≤ RCP; severe = METs > RCP) for each individual. Pearson’s chi-square tests over contingency tables were used to evaluate frequency distribution within intensity domains at each MET value. A multi-level regression model was performed to identify predictors of the amplitude of the exercise intensity domains.

Results

A critical discrepancy existed between the confines of the exercise intensity domains and the commonly used fixed MET classification system. Overall, the upper limit of the moderate-intensity domain ranged between 2 and 13 METs and of the heavy-intensity domain between 3 and 18 METs, whereas the severe-intensity domain included METs from 4 onward.

Conclusions

Findings show that the common practice of assigning fixed values of METs to relative categories of intensity risks misclassifications of the physiological stress imposed by exercise and physical activity. These misclassifications can lead to erroneous interpretations of the dose–response relationship of exercise and physical activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Gormley SE, Swain DP, High R, Spina RJ, Dowling EA, Kotipalli US, et al. Effect of intensity of aerobic training on V̇O2max. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1336–43.

Hickson RC, Foster C, Pollock ML, Galassi TM, Rich S. Reduced training intensities and loss of aerobic power, endurance, and cardiac growth. J Appl Physiol. 1985;58:492–9.

Rognmo Ø, Hetland E, Helgerud J, Hoff J, Slørdahl SA. High intensity aerobic interval exercise is superior to moderate intensity exercise for increasing aerobic capacity in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2004;11:216–22.

Shephard RJ. Intensity, duration and frequency of exercise as determinants of the response to a training regime. Int Z Für Angew Physiol Einschl Arbeitsphysiologie. 1968;26:272–8.

Ross R, De Lannoy L, Stotz PJ. Separate effects of intensity and amount of exercise on interindividual cardiorespiratory fitness response. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1506–14.

Huang G, Wang R, Chen P, Huang SC, Donnelly JE, Mehlferber JP. Dose–response relationship of cardiorespiratory fitness adaptation to controlled endurance training in sedentary older adults. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23:518–29.

Iannetta D, Inglis EC, Mattu AT, Fontana FY, Pogliaghi S, Keir DA, et al. A critical evaluation of current methods for exercise prescription in women and men. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52:466–73.

Mann T, Lamberts RP, Lambert MI. Methods of prescribing relative exercise intensity: physiological and practical considerations. Sports Med. 2013;43:613–25.

Jamnick NA, Pettitt RW, Granata C, Pyne DB, Bishop DJ. An examination and critique of current methods to determine exercise intensity. Sports Med. 2020;50:1729–56.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Herrmann SD, Meckes N, Bassett DR Jr, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Compendium of physical activities: a second update of codes and MET values. Med Sci Sports Exerc LWW. 2011;43:1575–81.

Jetté M, Sidney K, Blümchen G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin Cardiol. 1990;13:555–65.

Balke B. The effect of physical exercise on the metabolic potential, a crucial measure of physical fitness. In: Staley S, Cureton T, Huelster L, Barry AJ, editors. Exercise and fitness. Chicago: The Athletic Institute; 1960. p. 73–81.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, Jacobs DR Jr, Montoye HJ, Sallis JF, et al. Compendium of physical activities: classification of energy costs of human physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:71–80.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–512.

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;2019:140.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1334–59.

Haskell WL, Lee I-M, Pate RR, Powell KE, Blair SN, Franklin BA, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1423–34.

Lavie CJ, Ozemek C, Carbone S, Katzmarzyk PT, Blair SN. Sedentary behavior, exercise, and cardiovascular health. Circ Res. 2019;124:799–815.

Nelson ME, Rejeski WJ, Blair SN, Duncan PW, Judge JO, King AC, et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults: recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1435–45.

Pate RR. Physical activity and public health-reply. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1995;274:535–535.

Sallis JF, Haskell WL, Wood PD, Fortmann SP, Rogers T, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity assessment methodology in the five-city project. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:91–106.

Howley ET. Type of activity: resistance, aerobic and leisure versus occupational physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S364–9.

Holtermann A, Stamatakis E. Do all daily metabolic equivalent task units (METs) bring the same health benefits? Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:991–2.

Whipp BJ, Mahler M. Dynamics of pulmonary gas exchange during exercise. Pulm Gas Exch Vol II Org Environ. 1980;22:33–96.

Poole DC, Jones AM. Oxygen uptake kinetics. Compr Physiol. 2012;2:933–96.

Iannetta D, Inglis EC, Pogliaghi S, Murias JM, Keir DA. A “step-ramp-step” protocol to identify the maximal metabolic steady state. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2020;52:2011–9.

Rossiter HB. Exercise: Kinetic considerations for gas exchange. Compr Physiol. 2011;1:203–44.

Davies MJ, Benson AP, Cannon DT, Marwood S, Kemp GJ, Rossiter HB, et al. Dissociating external power from intramuscular exercise intensity during intermittent bilateral knee-extension in humans. J Physiol. 2017;595:6673–86.

Cannon DT, Howe FA, Whipp BJ, Ward SA, McIntyre DJ, Ladroue C, et al. Muscle metabolism and activation heterogeneity by combined 31 P chemical shift and T 2 imaging, and pulmonary O 2 uptake during incremental knee-extensor exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2013;115:839–49.

Poole DC, Ward SA, Gardner GW, Whipp BJ. Metabolic and respiratory profile of the upper limit for prolonged exercise in man. Ergonomics. 1988;31:1265–79.

Black MI, Jones AM, Blackwell JR, Bailey SJ, Wylie LJ, McDonagh STJ, et al. Muscle metabolic and neuromuscular determinants of fatigue during cycling in different exercise intensity domains. J Appl Physiol. 2017;122:446–59.

Krüger RL, Aboodarda SJ, Jaimes LM, Samozino P, Millet GY. Cycling performed on an innovative ergometer at different intensities–durations in men: neuromuscular fatigue and recovery kinetics. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2019;44:1320–8.

Ansdell P, Škarabot J, Atkinson E, Corden S, Tygart A, Hicks KM, et al. Sex differences in fatigability following exercise normalised to the power–duration relationship. J Physiol. 2020;598:5717–37.

Granata C, Oliveira RSF, Little JP, Renner K, Bishop DJ. Training intensity modulates changes in PGC-1α and p53 protein content and mitochondrial respiration, but not markers of mitochondrial content in human skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2016;30:959–70.

Egan B, Carson BP, Garcia-Roves PM, Chibalin AV, Sarsfield FM, Barron N, et al. Exercise intensity-dependent regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α mRNA abundance is associated with differential activation of upstream signalling kinases in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2010;588:12.

Whipp BJ. Domains of aerobic function and their limiting parameters. Physiol Pathophysiol Exerc Toler. Boston: Springer US; 1996. p. 83–9.

Iannetta D, Fontana FY, Maturana FM, Inglis EC, Pogliaghi S, Keir DA, et al. An equation to predict the maximal lactate steady state from ramp-incremental exercise test data in cycling. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21:1274–80.

Iannetta D, de Azevedo RA, Keir DA, Murias JM. Establishing the V̇O2 versus constant-work rate relationship from ramp-incremental exercise: simple strategies for an unsolved problem. J Appl Physiol. 2019;1519–27.

Keir DA, Fontana FY, Robertson TC, Murias JM, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM, et al. Exercise intensity thresholds: identifying the boundaries of sustainable performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:1932–40.

Iannetta D, de Almeida AR, Ingram CP, Keir DA, Murias JM. Evaluating the suitability of supra-PO peak verification trials after ramp-incremental exercise to confirm the attainment of maximum O 2 uptake. Am J Physiol-Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2020;319:R315–22.

Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY, Whipp BJ, Froelicher VF. Principles of exercise testing and interpretation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 1987;7:189.

Lamarra N, Whipp BJ, Ward SA, Wasserman K. Effect of interbreath fluctuations on characterizing exercise gas exchange kinetics. J Appl Physiol Bethesda Md. 1985;1987(62):2003–12.

Martin-Rincon M, González-Henríquez JJ, Losa-Reyna J, Perez-Suarez I, Ponce-González JG, de La Calle-Herrero J, et al. Impact of data averaging strategies on V̇O2max assessment: Mathematical modeling and reliability. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29:1473–88.

Kaminsky LA, Arena R, Myers J. Reference standards for cardiorespiratory fitness measured with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1515–23.

Neder JA, Jones PW, Nery LE, Whipp BJ, Neder JA. The effect of age on the power/duration relationship and the intensity-domain limits in sedentary men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2000;82:326–32.

Neder JA, Nery LE, Castelo A, Andreoni S, Lerario MC, Sachs A, et al. Prediction of metabolic and cardiopulmonary responses to maximum cycle ergometry: a randomised study. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1304–13.

Norton K, Norton L, Sadgrove D. Position statement on physical activity and exercise intensity terminology. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:496–502.

Sisson SB, Katzmarzyk PT, Earnest CP, Bouchard C, Blair SN, Church TS. Volume of exercise and fitness nonresponse in sedentary, postmenopausal women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:539–45.

Kujala UM, Pietilä J, Myllymäki T, Mutikainen S, Föhr T, Korhonen I, et al. Physical activity: absolute intensity versus relative-to-fitness-level volumes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:474–81.

Ismail H, McFarlane JR, Nojoumian AH, Dieberg G, Smart NA. Clinical outcomes and cardiovascular responses to different exercise training intensities in patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:514–22.

Church TS, Earnest CP, Skinner JS, Blair SN. Effects of different doses of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness among sedentary, overweight or obese postmenopausal women with elevated blood pressure: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2081.

Manson JE, Stefanick ML, Sheps DS. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2002;10:716–25.

Wen CP, Wai JPM, Tsai MK, Yang YC, Cheng TYD, Lee M-C, et al. Minimum amount of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:1244–53.

Lee I-M, Sesso HD, Oguma Y, Paffenbarger RS. Relative intensity of physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2003;107:1110–6.

Hupin D, Roche F, Gremeaux V, Chatard J-C, Oriol M, Gaspoz J-M, et al. Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged ≥60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1262–7.

Howden EJ, Perhonen M, Peshock RM, Zhang R, Arbab-Zadeh A, Adams-Huet B, et al. Females have a blunted cardiovascular response to one year of intensive supervised endurance training. J Appl Physiol. 2015;119:37–46.

Rengo JL, Khadanga S, Savage PD, Ades PA. Response to exercise training during cardiac rehabilitation differs by sex. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2020;40:319–24.

Byrne NM, Hills AP, Hunter GR, Weinsier RL, Schutz Y. Metabolic equivalent: one size does not fit all. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:8.

Kozey S, Lyden K, Staudenmayer J, Freedson P. Errors in MET estimates of physical activities using 3.5 ml·kg−1·min−1 as the baseline oxygen consumption. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7:508–16.

Mcmurray RG, Soares J, Caspersen CJ, Mccurdy T. Examining Variations of resting metabolic rate of adults: a public health perspective. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:1352–8.

Harris JA, Benedict FG. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1918;4:370–3.

Mezzani A, Corrà U, Giordano A, Colombo A, Psaroudaki M, Giannuzzi P. Upper intensity limit for prolonged aerobic exercise in chronic heart failure. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:633–9.

Van Der Vaart H, Murgatroyd SR, Rossiter HB, Chen C, Casaburi R, Porszasz J. Selecting constant work rates for endurance testing in COPD: The role of the power-duration relationship. COPD J Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2014;11:267–76.

Hansen D, Bonné K, Alders T, Hermans A, Copermans K, Swinnen H, et al. Exercise training intensity determination in cardiovascular rehabilitation: should the guidelines be reconsidered? Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019;26:1921–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Dr. Juan M. Murias was supported by NSERC Canada (RGPIN-2016-03698) and the Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada (#1047725).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards outlined by the institutional research committees of the University of Calgary and University of Verona and in conformity with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data availability

All data related to this study are presented within the manuscript.

Author contributions

DI, DAK, ECI, DHP, SP, and JMM conceived the study. DI, DAK, FYF, ECI, ATM and SP collected the data. DI, DAK, FYF, ECI, ATM, SP and JMM analyzed the data. All authors interpreted the data. DI wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically revised and contributed to the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Iannetta, D., Keir, D.A., Fontana, F.Y. et al. Evaluating the Accuracy of Using Fixed Ranges of METs to Categorize Exertional Intensity in a Heterogeneous Group of Healthy Individuals: Implications for Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Health Outcomes. Sports Med 51, 2411–2421 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01476-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01476-z