COVID Forced Schools to Innovate: Let’s Build on What They Learned

By Dan Weisberg, Tim Hughes, Katie Martin, and Devin Vodicka

The COVID-19 pandemic has tested public education in the United States like nothing else in recent memory. But with vaccination numbers on the rise, more schools are finally looking ahead to resuming in-person instruction—and confronting the potentially historic setbacks students suffered over the last year.

Helping students recover—socially, emotionally, and academically—will be a years-long effort that may prove even more challenging than the pandemic itself. Fortunately, schools have two powerful resources to draw on as they formulate their plans. The first has received plenty of attention: an unprecedented infusion of federal funding. Less well-known but just as important is the burst of promising new approaches to education that school systems, educators, and families pioneered in response to the crisis.

Across the country, schools rolled out and refined virtual instruction, partnered with community organizations to provide tutoring and other supports, and enlisted families as true partners in their children’s education like never before. Students and families adapted in creative ways, too, with many forming learning “pods” or more informal support networks. Familiar process-oriented metrics such as seat time were impractical measures of success, opening up new opportunities for communities to reflect on the purpose of schooling. This all happened mainly out of necessity: the traditional approach to school wasn’t possible, so we had no choice but to create alternatives.

But in their understandable haste to reopen buildings and welcome back students, it would be a mistake for schools to treat the work of the last year as relevant only during once-in-a-generation emergencies. After all, the traditional approach to school was failing to provide far too many students—especially students of color and those from low-income families—with the opportunities they deserve long before anybody had ever heard of COVID-19.

Instead of simply recreating the pre-pandemic educational experience, school and system leaders should consider which new instructional models from the last year have the potential to improve that experience for historically marginalized students over the long term—and set aside a percentage of new federal funding to expand them. Many of these “innovations” have actually been in development for many years and their utility has been magnified through the pandemic. More specifically, leaders should take this opportunity to:

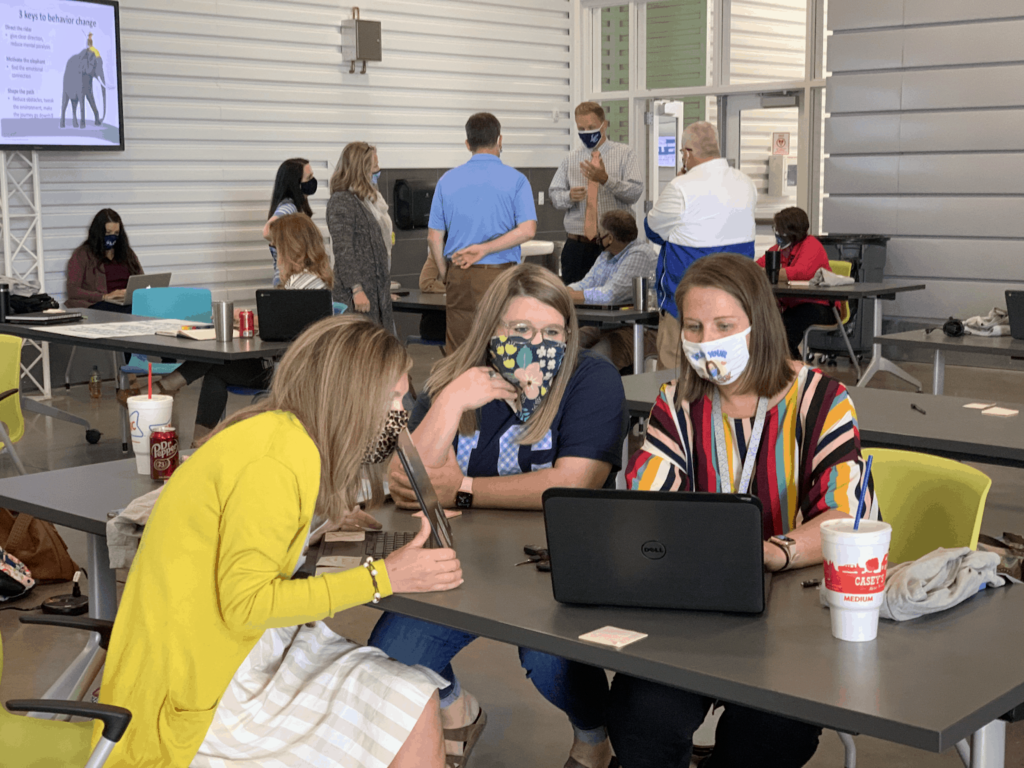

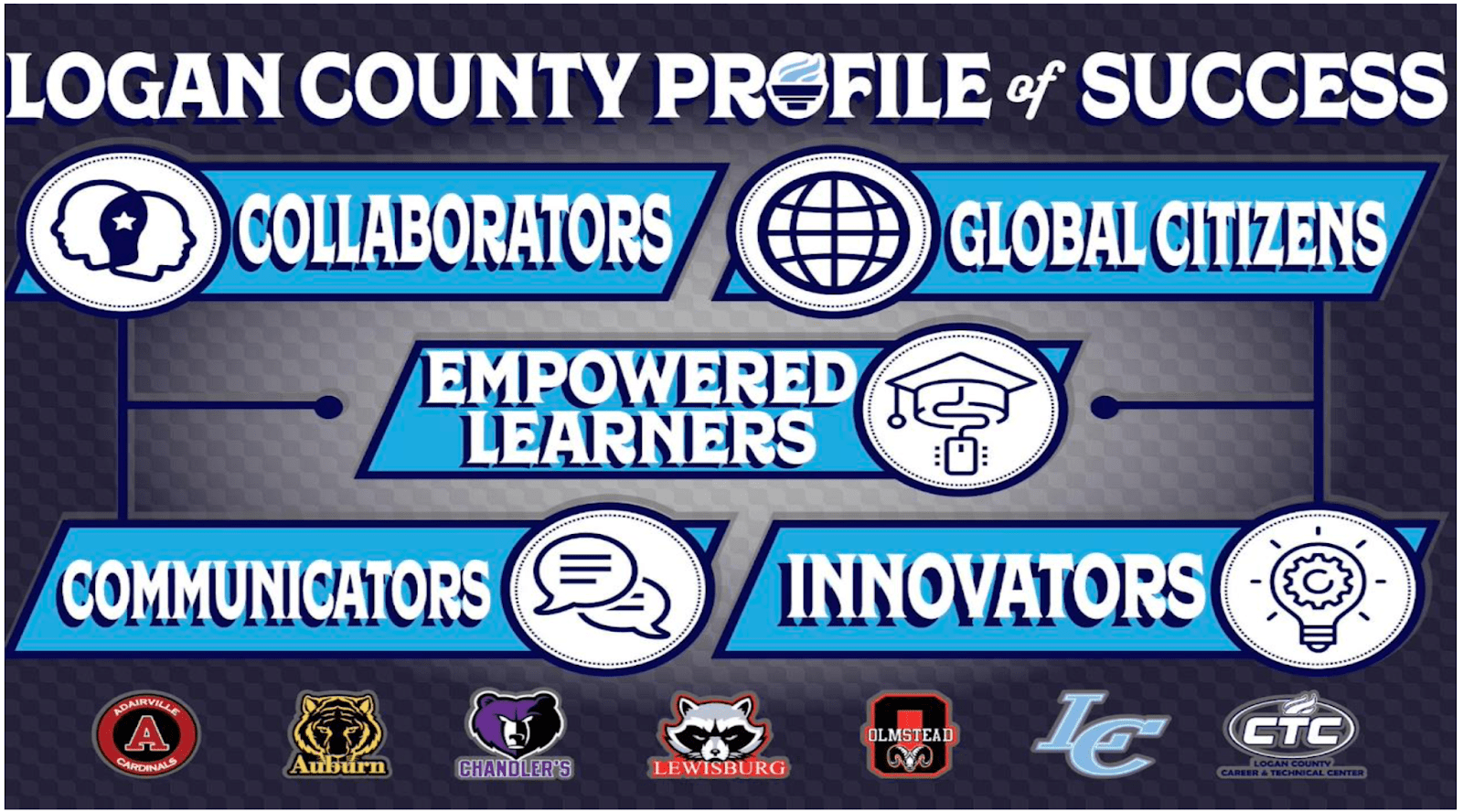

Expand our view of success: The pandemic has made it clear that we must focus on whole-child outcomes that include knowledge, habits, and skills. Logan County Schools in Kentucky has focused on developing their Profile of Success to name, teach, and grow skills beyond traditionally tested outcomes. Throughout the past year educators have come up with mentoring programs, varied schedules, leadership opportunities, personal schedules, and redesigned their class schedules to address the needs of the whole child. Many schools and systems have recognized the value of social-emotional learning, including building relationships and fostering both confidence and competence as learners. It is not sufficient to just teach the content. Instead, we have seen the value of teaching young people the skills to manage their responsibilities, find and use information, and learn to chart their own path to more holistic measures of success.

Adopt flexible learning schedules: The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provides funds to help schools set up extended learning this summer and in 2021-22—and many students will need this extra instructional time in order to accelerate back to grade-level after the interrupted learning of the last year. But even as they look for ways to offer more total instructional time, schools may want to consider maintaining some of the flexibility students experienced over the last year around exactly when they access lessons or complete assignments. For example, Guilford County Public Schools proposed hubs being in the evening for students whose life circumstances prohibit them from attending during the day. Bedford County Public Schools has eliminated master schedules at secondary schools, instead of assigning 12-15 students to a “learning coach” who meets with students routinely to promote connectedness and to develop flexible schedules that meet the needs of each learner.

Create a wider range of instructional roles: Schools will need as many great teachers as possible to help students recover from this crisis—but that’s just a starting point. Over the last year, many communities recruited college students, parents, grandparents, clergy, retired educators, and professionals whose jobs were disrupted by the pandemic to offer mentoring, tutoring, and support for virtual learning. There’s no reason these partnerships shouldn’t continue—and expand—in the years ahead . Central Falls has hired people from the community to serve as “pod leaders.” Most hubs have students doing remote learning provided by the district, sometimes supported by non-certified staff (The Mind Trust / IPS, Miami-Dade, Cleveland, Chicago). Over the long run, these and other new roles may provide models for a more formalized “apprentice” approach to the teaching profession.

Deliver instruction in more ways: School systems and local governments have prioritized expanding access to high-speed internet connections and devices during the pandemic. Some students who thrived doing more self-directed virtual learning may benefit from having it remain part of their school experience even after buildings reopen. And there’s certainly no reason to undo the progress we’ve made narrowing the digital divide just because the pandemic is waning. For example, Dallas ISD is building on their personalized learning school model with a distance learning option for families. More flexible instructional delivery models could also help ensure fewer students drop out simply because they can’t be in a school building for six or seven hours a day—for example, high school students who work during the day to help support their family financially.

Strengthen partnerships with families: When school buildings closed, many families and caregivers took on new roles as assistant teachers. Schools relied on families to make virtual learning possible—which meant prioritizing clearer communication and greater transparency about the work students were expected to do in their classes each day. This focus on authentic partnership with families should continue even after in-person learning resumes—and no family should accept a return to being in the dark about their child’s day-to-day school experiences. To promote strong family partnerships, Oakland is hiring “family liaisons” to support parents and Vista Unified School District has developed a network of Family and Community Engagement (FACE) specialists.

Not all these approaches will work for every school system—or even for every school within a given system. Leaders should take stock of what they piloted over the last year and zero in on the options that showed the most promising results for students. Above all, that means asking students and families from all parts of the communities directly about what worked and what didn’t before making any decisions, rather than relying on assumptions.

While many systems have evolved specific aspects of their previous school model, others have completely redesigned their conception of the school itself. These innovations are also coming together in new models of “school,” including pandemic pods, hubs, and micro-schools that can leverage many of the flexible benefits of personalization with the important social elements of learning communities. In these new models, staffing and family engagement structures are also modified, frequently promoting higher levels of connectedness between students and adults. Leveraging the recent infusion of ARPA funding, educators anywhere and everywhere can make small steps to implement these new models by running afterschool and summer programs that incorporate elements of these innovative models.

Let’s not aspire to return to “normal” and instead use what we have learned and expand promising innovations to better serve all students. At this moment, with the challenges so daunting and the stakes for students so high, school systems can and should create a new and better normal to move forward.

For more, see:

- Why Instructional Design Matters In Your Content Plan

- Reimagining Family Engagement in the Time of Covid

Dan Weisberg is the CEO of TNTP, an education nonprofit that helps school systems across the country address educational inequities and achieves their goals for students.

Tim Hughes is the West Vice President at TNTP.

Katie Martin is the Chief Impact Officer of Altitude Learning and the author of Learner-Centered Innovation.

Devin Vodicka is the CEO of Altitude Learning and the author of Learner-Centered Leadership.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.