ProPublica’s scrupulously reported new piece on Justice Clarence Thomas’ decadeslong luxury travel on the dime of a single GOP megadonor will probably not shock you at all. Sure, the dollar amounts spent are astronomical, and of course the justice failed to report any of it, and of course the megadonor insists that he and Thomas are dear old friends, so of course the superyacht and the flights on the Bombardier Global 5000 jet and the resorts are all perfectly benign. So while the details are shocking, the pattern here is hardly a new one. This is a longstanding ethics loophole that has been exploited by parties with political interests in cases before the court to curry favor in exchange for astonishing junkets and perks. It is allowed to happen.

We will doubtless spend a few news cycles expressing outrage that Harlan Crow has spent millions of dollars lavishing the Thomases with lux vacations and high-end travel and barely pretended to separate business and pleasure, giving half a million dollars to a Tea Party group founded by Ginni Thomas in 2011 (which funded her own $120,000 salary). But because the justices are left to police themselves and opt not to do so, we will turn to other matters in due time. Before the outrage dries up, however, it is worth zeroing in on two aspects of the ProPublica report that do have lasting legal implications. First, the same people who benefited from the lax status quo continue to fight against any meaningful reforms that might curb the justices’ gravy train. Second, the rules governing Thomas’ conduct over these years, while terribly insufficient, actually did require him to disclose at least some of these extravagant gifts. The fact that he ignored the rules anyway illustrates just how difficult it will be to force the justices to obey the law: Without the strong threat of enforcement, a putative public servant like Thomas will thumb his nose at the law.

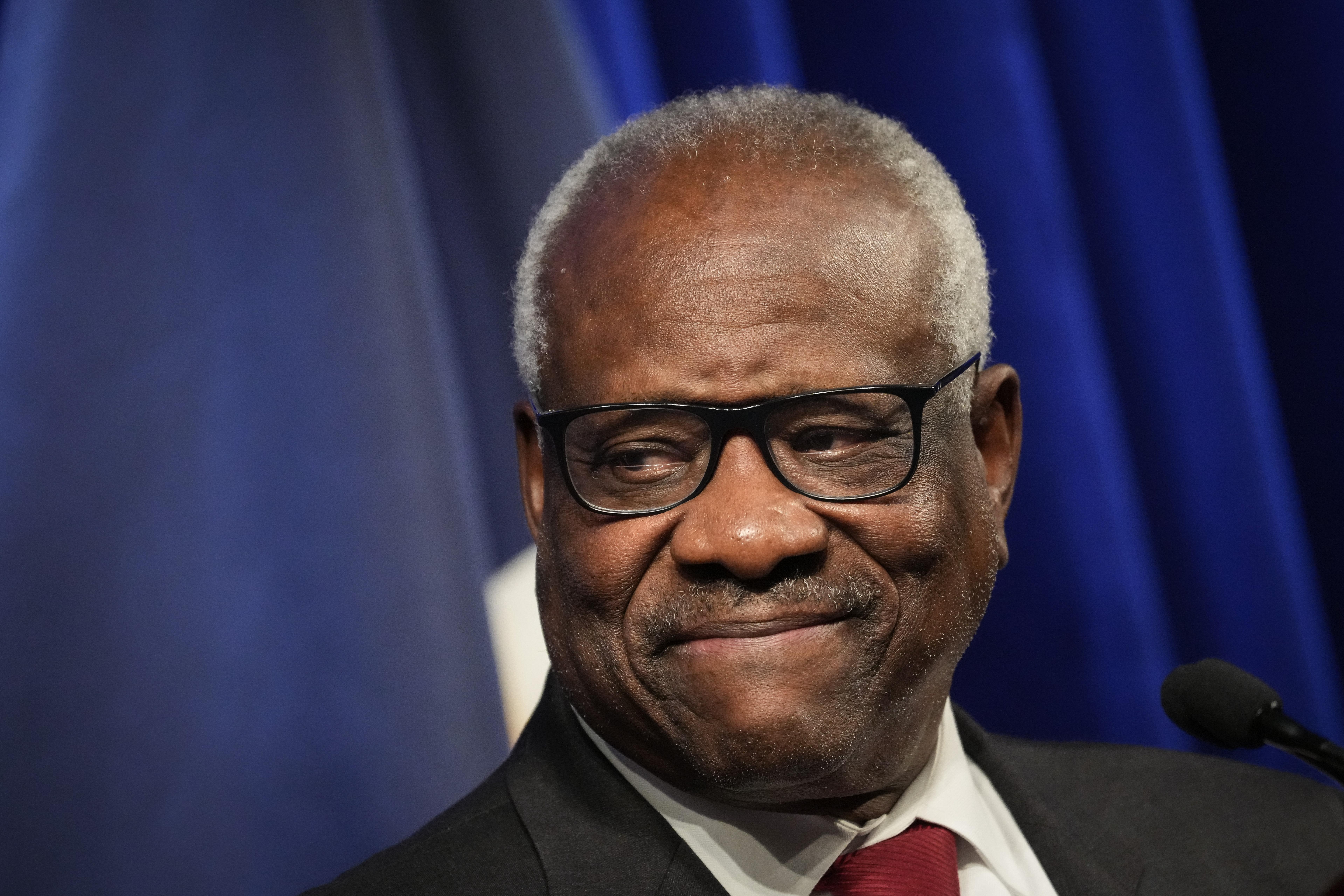

If there is a single image that captures this seedy state of affairs, it is a painting of Thomas hanging out with Leonard Leo (Federalist Society co-chair and judicial power broker) and Mark Paoletta (who has served as chief counsel to former Vice President Mike Pence and general counsel of Donald Trump’s Office of Management and Budget). Both are political operatives, though Crow assures us that they would never dare talk about Thomas’ work. This image should be enough to shock anyone into taking action against the spigot of dark money that flows directly from billionaire donors into the court, its justices, and their spouses’ pockets. Continuing to live as though there is nothing to be done about any of this is a choice. We make it every day.

In addition to working in the Trump-Pence administration, Paoletta serves as the Thomases’ longtime fixer, attack dog, and booster. He represented Ginni Thomas when she spoke to the Jan 6. committee about her support for overturning the 2020 election. He also edited a biography of Clarence Thomas based on an almost comically obsequious documentary (in which he was also involved). So it should not be a surprise that Paoletta has also testified against any ethics reform measures for the Supreme Court, dismissing the reform movement as part of “the coordinated campaign by some Democrats and their allies in the corporate media to smear conservative Justices with the goal of delegitimizing the court.”

The lack of a binding ethics code for justices redounds to Paoletta’s benefit: ProPublica reports that he joined the Thomases on a trip through Indonesia’s Lesser Sunda Islands on the Crows’ yacht. At the time, Paoletta was serving in the Trump administration, and was therefore subject to far stricter ethics rules than the justice; he told ProPublica that he reimbursed Crow for the trip, although he would not give a price tag. (It is an extraordinary feat for a public servant to be able to afford a private international yacht adventure; it also proves that even in government posts that actually have enforceable ethics rules, those rules may not be up to the job of policing corruption.)

This story is a perfect example, in miniature, of how Thomas’ network of benefactors ensure the justice’s billionaire lifestyle stays off the books. Paoletta testifies before Congress that ethics reforms are evil; Crow funds the Republican lawmakers who ensure ethics reforms don’t pass; and nobody knows the extent of Thomas’ unceasing stream of gifts until ProPublica reporters wrangle the details from yacht crews and flight records.

We should pause here to note that the situation is not entirely hopeless: Just last month, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts issued new guidance directing justices to disclose the kind of gifts that Thomas has enjoyed for decades. Indeed, in retrospect the guidance almost seems designed to force Thomas into reporting trips, flights, vacations, and other opulent presents from his pals. These rules have long exempted “personal hospitality” from disclosure requirements. But the new guidance clarifies that “personal hospitality” does not include “gifts other than food, lodging or entertainment, such as transportation that substitutes for commercial transportation.” And it explicitly states that stays at “property or facilities” owned by an entity (like the private resorts Thomas frequents) must be disclosed, even if they’re owned “wholly or in part by an individual.”

There is some dispute about whether the new guidance captures Thomas’ conduct for the first time ever, or if it merely bolds, italicizes, and underlines what should’ve already been obvious. ProPublica cites ethics experts who say that at least some of Thomas’ behavior was prohibited under the old guidance. NBC News cites an ethics expert who says the justice’s behavior was arguably permissible, even if it rested on an interpretation that was, at best, “a stretch.” This question is not academic: The answer determines whether Thomas’ conduct prior to the promulgation of the new rule was outright illegal or simply unseemly.

We align ourselves with the former view: Clarence Thomas broke the law, and it isn’t particularly close. The best argument in his defense is that the old definition of “personal hospitality” did not require him to disclose transportation, including private flights. This reading works only by torturing the English language beyond all recognition. The old rule, like the statute it derives from, defined the term as hospitality that is “extended” either “at” a personal residence or “on” their “property or facilities.” A person dead-set on defending Thomas might be able to squeeze these yacht trips into this definition, arguing that, by hosting Thomas on his boat for food, drink, and sightseeing, Crow “extended” hospitality “on” his own property. But lending out the private jet for Thomas’ personal use? Come on. There’s no plausible way to shoehorn these trips into the old rule—which quotes the statute verbatim—even under the most expansive interpretation imaginable. Letting somebody use your private jet to travel around the country is not “extend[ing]” hospitality “on” your property. It is lending out your property to someone else so they can avoid paying for a commercial flight. Thomas broke the law, a law which contains serious civil penalties, though the bogus technicality on which he relies, in addition to his political clout, will be more than enough to ensure that he never faces any actual legal consequences.

If you need further evidence, there’s another, equally clear indication about the nature of the hospitality exception to the disclosure requirement in a neighboring provision of the statute. This section explains which gifts, exactly, a justice must include in their annual report. It reiterates the exception for “personal hospitality,” but provides an even clearer definition of the types of hospitality at issue: “any food, lodging, or entertainment received as personal hospitality of an individual need not be reported.” (Emphasis added.) This language confirms the narrow scope of the hospitality exception: It covers housing, meals, and activities provided during a visit. It does not cover transportation. And even if you read an implied inclusion of transportation to reach the “lodging”—which is implausible, but whatever—that does not cover Crow lending Thomas his jet to fly around for the justice’s personal adventures.

For years we have been hearing from the justices that it’s not their fault so many parties with business before the court are also their best friends. We’ve heard that it’s not on them to stop generous pals from lavishing gifts upon them. We have been given to understand—as Justice Antonin Scalia explained in justifying his own travels with parties litigating before him—that justices need to hang out with fabulous and wealthy movers and shakers because who else is there to hang out with. Oh, and for years we have swallowed the pablum that these trips are so intrinsically fun and interesting that Clarence Thomas, Leonard Leo, Mark Paoletta, and a megadonor can sit around for hours chatting about sports, and not talking about any past, present, or future matter that may come before the court.

Within the legal community, this state of affairs is all justified on the grounds that no justice can retire to become a millionaire lobbyist or general counsel (because, naturally, they must protect the seat). And so unlike regular politicians—as well as other life-tenured judges who step down to take lucrative positions in private practice—the justices are tragically trapped in jobs that don’t pay what they think they are worth. The logic that allows interested parties to buy access by funneling cash to the Supreme Court Historical Society, or judicial spouses, or to million-dollar luxury travel is seen as perfectly acceptable. Indeed, it’s somehow seen as reasonable compensation for lost opportunities—a more dignified alternative to the revolving door. And so long as we believe Supreme Court justices are quasi-monarchs who are entitled to live like lords, they will find ways to live like lords. Those who can afford to purchase their lordliness will pony up whatever it takes. And we will all say that it’s awful. Until we learn about the next one, and the next one, and the one after that.