Winston Churchill and Islam—Part Two

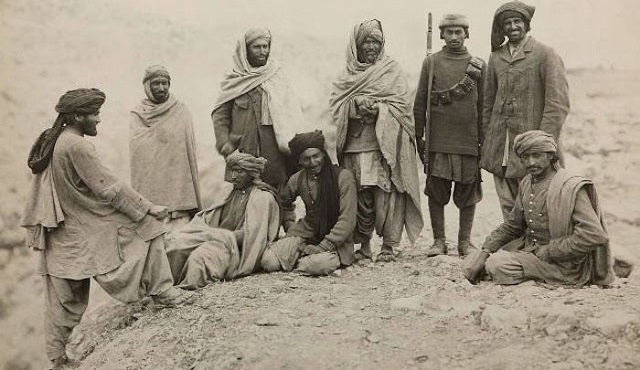

Churchill biographer Con Coughlin also describes their character in unflattering terms: “The Pashtuns invariably used violence to resolve their differences, which led to feuds between families lasting for generations. The Pashtun language even contains a specific word to define revenge between cousins. In many respects these frontiersmen were warriors in the Homeric sense, enjoying fighting for its own sake, often internecine, for the blood feud was central to their way of life. They took offence easily, were jealous of their personal honour and savagely cruel to any opponent no longer able to defend himself. They tortured, mutilated and killed without compunction.”[1] The modern-day “Taliban remains predominantly a Pashtun movement.”[2]

Churchill came to the same conclusion. Churchill begins his 1898 book, The Story of the Malakand Field Force: An Episode of Frontier War, by giving us the physical and anthropological context of the expedition:

Every tribesman has a blood feud with his neighbor. Every man’s hand is against the other, and all against the stranger….Every influence, every motive, that provokes the spirit of murder among men, impels these mountaineers to deeds of treachery and violence. The strong aboriginal propensity to kill, inherent in all human beings, has in these valleys been preserved in unexampled strength and vigour. That religion [Islam], which above all others was founded and propagated by the sword—the tenets and principles of which are instinct with incentives to slaughter and which in three continents has produced fighting breeds of men—stimulates a wild and merciless fanaticism. The love of plunder, always a characteristic of hill tribes, is fostered by the spectacle of opulence and luxury which, to their eyes, the cities and plains of the south display. A code of honour not less punctilious than that of old Spain, is supported by vendettas as implacable as those of Corsica.[3]

Churchill notes the Pathans’ (Pashtuns’) contradictory character, and, despite their chivalry, they treat their women as objects to be bought sold, or bartered.

We see them in their squalid, loopholed hovels, amid dirt and ignorance, as degraded a race as any on the fringe of humanity: fierce as the tiger, but less cleanly; as dangerous, not so graceful. Those simple family virtues, which idealists usually ascribe to primitive peoples, are conspicuously absent. Their wives and their womenkind generally, have no position but that of animals. They are freely bought and sold, and are not infrequently bartered for rifles. Truth is unknown among them. A single typical incident displays the standpoint from which they regard an oath. In any dispute about a field boundary, it is customary for both claimants to walk round the boundary he claims, with a Koran in his hand, swearing that all the time he is walking on his own land. To meet the difficulty of a false oath, while he is walking over his neighbor’s land, he puts a little dust from his own field into his shoes. As both sides are acquainted with the trick, the dismal farce of swearing is usually soon abandoned, in favor of an appeal to force.[4]

All are held in the grip of miserable superstition. The power of the ziarat, or sacred tomb, is wonderful. Sick children are carried on the backs of buffaloes, sometimes sixty or seventy miles, to be deposited in front of such a shrine, after which they are carried back—if they survive the journey—in the same way. It is painful even to think of what the wretched child suffers in being thus jolted over the cattle tracks. But the tribesmen consider the treatment much more efficacious than any infidel prescription. To go to a ziarat and put a stick in the ground is sufficient to ensure the fulfillment of a wish. To sit swinging a stone or coloured glass ball, suspended by a string from a tree, and tied there by some fakir, is a sure method of securing a fine male heir. To make a cow give good milk, a little should be plastered on some favorite stone near the tomb of a holy man. These are but a few instances; but they may suffice to reveal a state of mental development at which civilization hardly knows whether to laugh or weep.”[5]

Thus they are all held in the grip of superstition, which leaves them open to chicaneries of their mullahs, the religious class:

Their superstition exposes them to the rapacity and tyranny of a numerous priesthood ‘Mullahs,’ ‘Sahibzadas,’ ‘Akhundzadas,’ ‘Fakirs,’—and a host of wandering Talib-ul-ilms, [precursers of modern-day Taliban] who correspond with the theological students in Turkey, and live free at the expense of the people. More than this, they enjoy a sort of droit du seigneur, and no man’s wife or daughter is safe from them. Of some of their manners and morals it is impossible to write. As Macaulay has said of Wycherley’s plays, ‘they are protected against the critics as a skunk is protected against the hunters.’ They are ‘safe, because they are too filthy to handle, and too noisome even to approach.’[6]

AUTHOR

NOTE: Read Winston Churchill and Islam—Part One

[1] Con Coughlin, Churchill’s First War, p.127.

[2] Con Coughlin, Churchill’s First War, p.128.

[3] MFF, pp.3-4.

[4] MFF, Chapter 1, p.7.

[5] MFF, p.7

[6] MFF Chapter 1, pp.7-8.

EDITORS NOTE: This Jihad Watch column is republished with permission. ©All rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!