This is the book of a journey: young American reporter identifies a puzzle, and sets out to solve it, mostly by talking to the people who set him the puzzle – and therefore must have the answers – and then by trying for himself, and discovering he can do it.

It's a good way to explore a certain kind of science, especially the essentially subjective science of memory. It's a good way to introduce a new readership to new research: the reporter becomes an innocent, a Candide figure, to whom things happen, good and bad; who listens to everybody, both the wise and the wise guys.

The downside is that if you've already read a book about memory, you'll have been on some of the journey already. The upside is the reminder that discovery is fun.

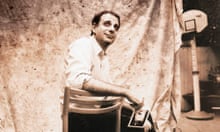

At its best, Moonwalking with Einstein is a delightful book. It begins with a young stay-at-home who goes out on an interview, gets to thinking distractedly about superlatives of strength and intellect, goes home again, searches Google for the cleverest human, and discovers "if not the smartest person in the world, at least some kind of freakish genius" who can memorise 1,528 random digits in one hour and any poem handed to him. It ends with Foer – who cannot remember where he put his car keys – in the finals of the USA Memory Championship, the product not so much of intellectual firepower as determination, technique and luck.

Early in the story he observes astonishing feats of mental athletics at a memory championship – someone recites back 252 random digits as effortlessly as if it had been his own telephone number – and is told that "anybody can do it". He encounters Ed, a shambling 24-year-old from Oxford who becomes his mentor; he meets Tony Buzan, the trim 67-year-old English self-help guru who founded the World Memory Championships in 1991 and who insists the brain is "like a muscle": exercise it and it gets stronger.

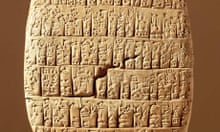

These twin starting points take Foer back in time to the classical world, and the first essay on memory, in a little Latin textbook from 82 BC; and to the legend of Simonides of Ceos, the poet from the 5th century BC who is credited with inventing the notional "memory palaces" in which contestants "place" the objects or abstractions they wish to remember, first having given them physical characteristics with which to recall them. The memory palace technique exploits the fact that we have a better memory for spaces, places and faces than for names and numbers: it's much easier to recall that someone is a baker, than that his surname is Baker.

It also takes him to the laboratories of cognitive science, and to the literature of memory: to the famous Russian journalist identified in 1928 who could remember everything; and to those tragic victims of illness and injury who can recall nothing for more than a few seconds.

He gets to know the psychologist who first identified the "phenomenon of seven" – the number of things you can keep in your head at any time, give or take one or two – and explores the still uncertain mechanics and neuroscience of short-term, working and enduring memory.

He recalls Jorge Luis Borges's famous story Funes the Memorious. He explores the historic past: the traditions of memory that existed before the invention of writing. He contemplates the bardic tradition of recited poems; he reflects on Homer and the repetitive insistence on a sea that is wine-dark and a dawn that is rosy-fingered.

He discovers, to his surprise, that learning a poem is harder than memorising a string of nonsense numbers or the order of a shuffled deck of cards. He crosses the Atlantic and puts himself under the tutelage of Ed, and gets to know the eccentric collection of souls who compete in the memory championships: "a bunch of guys (and a few ladies) widely varying in both age and hygienic upkeep".

Moonwalking with Einstein is huge fun to read, intellectually rewarding and chronicles a lot of drunk and nerdy behaviour. But what in the end does Foer gain from his newfound capacity for total recall under testing conditions? A good book, certainly, and a better memory – but not vastly better. He goes to dinner with friends and afterwards doesn't just forget where he parked his car: he goes home by subway having forgotten that he drove to dinner in the first place.

Tim Radford's The Address Book: Our Place in the Scheme of Things (Fourth Estate) was longlisted for the Royal Society Winton Science Book prize

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion