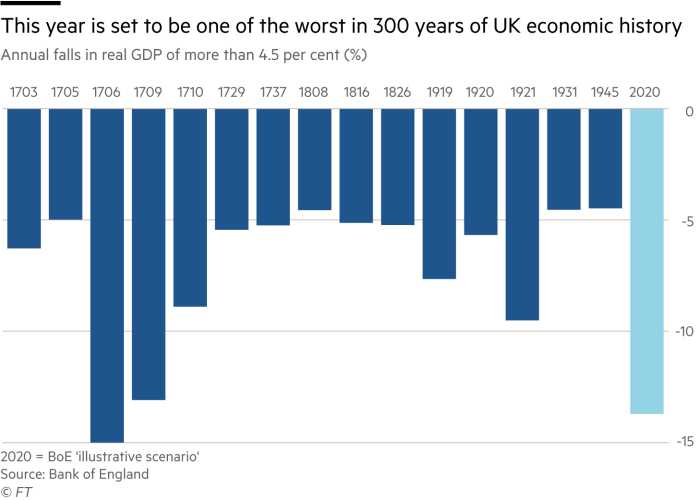

BoE warns UK set to enter worst recession for 300 years

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Bank of England has forecast that the coronavirus crisis will push the UK economy into its deepest recession in 300 years, with output plunging almost 30 per cent in the first half of the year, but it decided not to launch a new stimulus.

In its monetary policy report, the central bank presented rough and ready predictions for the economy, suggesting that output would slip 3 per cent in the first quarter followed by a further 25 per cent fall in the second. This would mean an almost 30 per cent drop overall in the first half of 2020, the fastest and deepest recession since the “great frost” in 1709.

The economic projections came with a warning to Britain’s banks that if they tried to stem losses by restricting lending, they would make the situation worse.

Andrew Bailey, the BoE governor, said a failure to lend would create a vicious circle of more bankruptcies and higher losses on loans that would come back to hit the banks themselves.

Speaking to journalists, Mr Bailey said: “The better path for banks is to keep lending . . . we keep banging this message home. If the system [ensures a good supply of loans], we’ll get a better outcome.”

Commercial banks responded that they were committed to lending through the crisis. Alison Rose, NatWest chief executive, said the bank was “committed to providing our customers, communities and colleagues with the support they need”.

Speaking at Barclays’ annual general meeting on Thursday, Jes Staley, chief executive, pledged that his bank would emerge with “a reputation as having stood with the citizens of Great Britain in this time of crisis”.

António Horta-Osório, chief executive of Lloyds Banking Group, last week said the bank was working with government and regulators “to ensure that we play our part in supporting our customers and the UK economy”.

But the BoE cautioned that, even with adequate lending, the economy was bound to take a big hit; household spending has dropped about 30 per cent since early March.

The central bank forecast that the UK’s unemployment rate was likely to rise to 9 per cent in 2021, even with the government’s job retention scheme protecting many employees from being laid off. That would mean a higher rate of joblessness than after the 2008-09 financial crisis.

The central bank also forecast that inflation would dip to 0.5 per cent in 2021, before returning to the 2 per cent target the following year.

In contrast to the gloomy assessment of the current economic position, the longer-term economic projections were more upbeat, with the BoE expecting “only limited scarring to the economy”.

The bank’s back-of-the-envelope scenarios assumed long-term damage to the economy would be only 1.5 per cent of gross domestic product and would come from missed business investment in 2020. Otherwise it predicted the economy would bounce back in a V-shaped recovery.

Mr Bailey said the economic rebound was likely to happen “much more rapidly than the pullback from the global financial crisis”.

The BoE said it stood ready to put more money into the economy should it be needed and had further meetings planned for June — before the £200bn it pledged in March to support economic activity by buying government bonds was likely to run dry.

Mr Bailey defended the decision not to take more immediate action, saying the measures announced in March had not been exhausted. “It’s a very aggressive [asset] purchasing programme . . . [and] we have made a very clear commitment to do what it takes to support the economy consistent with [meeting] the inflation target.”

Not all Monetary Policy Committee members supported the majority decision. Two of the nine members, Jonathan Haskel and Michael Saunders, voted to increase quantitative easing by another £100bn immediately, seeking more stimulus to prevent greater scarring of the economy later.

All MPC members agreed that more stimulus might be needed in future. In the minutes, the committee said: “For all members of this group, the prospective weakness in employment and inflation, and downside risks around aspects of the medium-term outlook, might necessitate further monetary policy action.”

Along with most economists, Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said he thought the central bank was signalling that “more QE is coming, if not in June, then in August”.

The BoE also undertook an exercise to test whether the financial system could cope with the expected once-in-a-century recession.

It assessed that banks would lose less money than in its latest stress test and concluded that “the core banking system has capital buffers more than sufficient to absorb losses”.

It did, however, stress the pandemic would severely hit corporate cash flow. It said that while UK companies normally operate with a cash flow deficit of £80bn, the crisis would raise that to £190bn. Government support would plug some of the gap, but there remained a £60bn additional deficit that banks would need to cover to stop viable businesses from going under.

In the financial stability section of its report, the central bank warned that if high-street lenders failed to provide credit to their business customers, they might see a short-term benefit in reduced losses, but would cause more companies to fail and unemployment to rise another 2 percentage points, ultimately leading to larger losses.

Additional reporting by Stephen Morris

Comments