Music

VANISHING POINT: Will the RIAA and MPAA Wipe International Music Off the Globe?

In Hollywood and the Recording Industry Association of America’s unchecked attempt to keep the world safe for Lady Gaga and Harry Potter, we’re seeing the beginning of the possible destruction of the web as a site for virtual libraries, archives, and—most important—community.

It’s impossible to measure the full impact of the January 19 FBI shutdown of the Megaupload site (often referred to by users as MU). Incorporated in Hong Kong but run out of New Zealand, MU was the most popular file-sharing site on the web, with more than 180 million registered users. According to MU’s founder, Kim Dotcom, some 50 million of those people were using the site for perfectly legal storage and sharing; but even if it were really a much smaller percentage—let’s say one or two percent—at least a couple of million totally innocent people had everything they’d parked in MU’s sizeable corner of the cloud rendered inaccessible overnight, without warning, and apparently with no way of getting any of it back.

Among the hardest hit were the collectors, sharers, listeners, and scholars who make up the international music blogging community. Literally overnight, tens of thousands of long out-of-print and unavailable musical treasures were rendered inaccessible, historical artifacts of expressive and once-popular culture from around the world.

Sharity Begins at Home

Music bloggers are not universally loved, not even by the people who benefit from their activities—and not even by everyone with a music blog. In his book Retromania, music critic Simon Reynolds admits to, at one point, downloading 30 full-length albums simultaneously, and describes the sharity (“sharing” + “rarity”) music blog phenomenon as yet another symptom of our oversaturated, ADD-plagued age, and sharity bloggers themselves as competitively generous show-offs who want the world to know how cool and esoteric their taste is.

Eric Lumbleau, whose popular Mutant Sounds site (mutant-sounds.blogspot.com) lost at least 150 albums in the FBI’s MU shutdown, is unconcerned about his own loss and that of the music community’s generally. “Things have been lost in the short term, but an infinite number of enterprising music blogger hamsters on an infinite number of spinning wheels will surely see fit to create a new informational tsunami in no time.”

Going forward, Eric says Mutant Sounds plans to avail itself of the soon-to-be-launched Righthaven.com, which promises to be a kind of Swiss bank for cyberlocker users. “The United States is, let’s face it, the leading source and exporter of frivolous intellectual property litigation in the world,” Righthaven explains on their temporary homepage. “Therefore, we are beyond pleased to have retained the services of internationally known First Amendment and IP lawyer Marc J. Randazza, of the Randazza Legal Group, and Kenneth White, a Partner at Brown White & Newhouse LLP, whose practice includes First Amendment and federal criminal defense.” That (and the fact that they actually are located in Switzerland) could make them a future favorite with sharity bloggers trafficking in legally gray-area works.

The Burning of the Alexandrian Library

Being relatively new to music blogging myself, I don’t yet share Reynolds’s jaundiced view of the medium, nor Lumbleau’s devil-may-care attitude about the recent MU shutdown, which practically decimated some of my favorite sites, including Global Groove, Holy Warbles, and—above all—Madrotter.

Henk den Toom, who curates Madrotter (madrotter.blogspot.com), lost 1,500 albums. All but the most recent links on his blog (he’s switched, temporarily, to Mediafire) are dead. A self-described “Dutch guy living in Bandung since 1996,” Henk began collecting out-of-print Indonesian cassettes and vinyl while producing music for local hip-hop acts.

“I bought some traditional records to sample from,” he told me recently via e-mail. “The records that really hit me hard were by Titim Fatimah. I started asking about her and discovered that almost nobody had ever heard of her, which amazed me, because in her day she was really one of the biggest stars here.”

Henk was already blogging, mostly sharing hip-hop. “There isn’t really that much good Indonesian hip-hop, at least not enough to keep a blog running,” he explained. “So I just started blogging about Indonesian music I liked. Pretty soon I was buying stuff left and right. I got very lucky: A seller called me and said he knew a radio station that was closing up near Cirebon. I went there with him and got my hands on 1,200 albums, all for around 400 U.S. dollars.”

Henk’s collection swelled to some 3,000 records and just shy of 700 cassettes, about a third of which he’d made available on Madrotter. (Compare that to the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Music of Indonesia series—a mere 20 CDs, or about 1/100 of what Madrotter offered for free.) Now in its fourth year of operation, the blog receives an average 45,000 visitors a month, many of them appreciative listeners in Henk’s adopted archipelago. As international music, including Indonesia’s rich and varied history, becomes increasingly sought-after globally, Henk notices it’s getting harder to find things to share. Most buyers are scooping up product at dirt-cheap prices to resell at handsome profits on eBay.

As a result, Henk argues, “Indonesia is losing a part of its cultural treasure, and the result is that Indonesians can’t find or even afford to buy this stuff anymore. There’s one foreigner living not that far from Bandung who has been buying thousands of cassettes of traditional Sundanese music and shipping them off to his homeland. People from the local traditional music communities feel that he’s robbing them of their culture. He actually has a website where he claims he’s ‘preserving Sundanese culture,’ but has so far shared only 50 songs out of the tens of thousands he’s taken out of circulation.”

I asked Henk how he’s managed to maintain enthusiasm for his blog for so long and especially after having his online library wiped out. “The incredible love I get from people who love what I do, especially from Indonesian people. I feel that, in some way, what I’m doing is important. A lot of this music was really just vanishing.”

The Assassination of Owl Qaeda

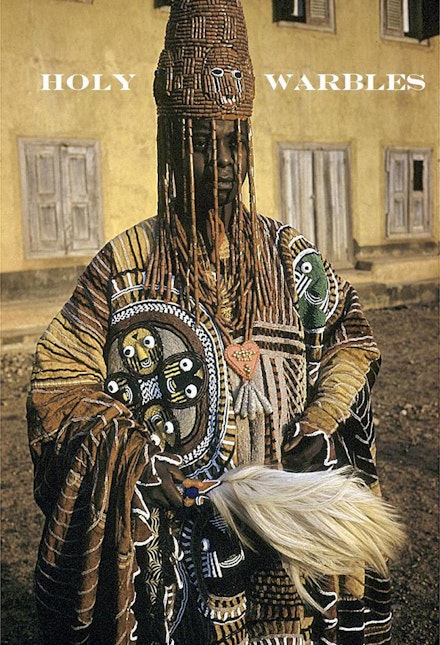

Not everyone is as resilient as Henk. One of the most beloved music archives on the web, Holy Warbles (holywarbles.blogspot.com) lost everything in the FBI’s MU raid. As if that weren’t enough, days later Blogger shut down the blog itself, claiming multiple instances of copyright infringement. Run by the colorfully monikered Owl Qaeda, whose avatar is a real (possibly stuffed) owl in turban-y headdress, Holy Warbles trafficked in rare and out-of-print 20th-century popular and folk music from all over the world.

The last thing I downloaded from the Owl was an out-of-print album by Marie Jubran, a Syrian artist active from the 1920s up until her death in the 1950s, who doesn’t have so much as an English-language Wikipedia page (though there is one in French). I have a lot of Arabic music from the period and a couple of related books, and this was the first time I’d heard of her. Jubran’s voice is extraordinary. But, like a lot of other extraordinary singers from the Middle East of that time, her career was eclipsed by superstars like Oum Kalsoum and the monopoly of Sono Cairo, which—until the advent of the cassette and a subsequent flourishing of labels—ensured that all but a handful of singers from the region would vanish into obscurity. (Ever wonder why you’ve only ever heard of Kalsoum, Fairuz, Asmahan, Farid El-Atrache, and Abdel Halim Hafez? It’s virtually the same reason that the only Indian singers you’re likely to know are Lata Mangeshkar, her sister Asha Bhosle, and Mohammad Rafi. Monopolies, corporate or otherwise, have a way of making their voices, and only their voices, heard.)

Doug Schulkind, who DJs and blogs for WFMU in New Jersey, devoted his January 27 broadcast to Holy Warbles, playing some of his favorite finds from the now-defunct blog over the years. (The show is archived at wfmu.org/playlists/shows/43637.) I asked Schulkind what made the Owl’s sharing unique.

“Holy Warbles was, first and foremost, a hub of communal celebration,” he said. “Host Owl Qaeda took great pleasure in presenting each new selection and treated the artists and their recordings with utmost respect. His choices were so uniformly thrilling that being presented at Holy Warbles became a kind of imprimatur of excellence. Owl Qaeda took the time to tell a story about each offering, reprinting the best available descriptions from other sources and always adding a brief personal bit of irreverent commentary, the perfect frame for enjoying and appreciating the sounds on display.”

Schulkind was not the only person to publicly mourn the loss of Holy Warbles—all over the internet eulogies and rants were posted on an almost hourly basis.

“Holy Warbles was the source of outrageous pleasure-taking for a worldwide audience of the open-minded,” Schulkind explained. “Threads of discussions about the music on display unfolded in the comments to many posts, with visitors enhancing the experience with additional information and links to further sources of discovery. The shuttering of Holy Warbles is a smack in the face of all who came to the site for the love of the music. For readers, the loss of Holy Warbles is like the loss of a friend—a smart, thoughtful, conscientious, and occasionally hilarious friend. For the artists and their creations, it’s just another in a long line of corporate interests screwing them out of something.”

The Blog as Public Square

Schulkind’s description of Holy Warbles makes it sound more like a public square, a place of communal gathering, than a music blog—or even a library. This sense of the music blog as meeting place for like-minded people is shared by others, including Deejay Moos, who runs Global Groove (globalgroovers.blogspot.com) and lost 1,200 files housed on MU—nearly four years’ worth of work, 98 percent of which he claims was “otherwise unobtainable.”

Moos started blogging in 2008, inspired by the Brazilian sharer Zecalouro’s Loronix (loronix.blogspot.com). When ill health forced Zecarlouro into retirement, Moos visited him in Rio; when he returned, he launched Global Groove. For Moos, who says he sometimes feels like a “music missionary,” sharity blogging seems as much about the creation of community as anything else.

“I could never find anyone in my immediate surroundings who shared my passion for this music,” he told me. The expressions of love and thanks Moo receives from visitors—many with blogs of their own—compel him to continue, even in this uncertain, post-MU world. “What a shame if all of the music I’ve found just stays on my shelf—music belongs to everyone.” Sharing, for Moos, is a form of communication. And, as American existential psychologist Rollo May once wrote, “Communication leads to … understanding, intimacy and mutual valuing”—the very essence of community.