Sunday, April 01, 2012

Vygotsky (1896-1934) - social construction, mediation, ZPD, language, play & special needs

Friday, June 09, 2023

Vygotsky, language, intelligence and AI

Vygotsky is an oft-quoted but rarely read learning theorist. Let me start by saying I am not a social constructivist but in using ChatGPT3.5 and 4, I have become more Vygotskian, as I have come to see ChatGPT as similar to the concept of the Vygotskian teacher. He gives us insights into why language is key to intelligence and why Generative AI may be the most powerful form of learning technology we have ever invented.

Learn from language

LLMs are fundamentally Vygotskian. They have been trained on data (language) as created and used by us, and therefore they learn from us. There is another step, where humans train the model further by making judgements to make the output more palatable through what is called Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

Knowledgeable other

Just as Vygotsky thought of language as a mediating source for learning, so LLMs use this form of mediation by language. It has been further trained by real humans to align it with our expectations. This is how babies and children learn. They listen, are spoken to and guided by adults. When we use a LLM we are like young children asking questions and being given responses by what Vygotsky calls a ‘knowledgeable other. That knowledgeable other is AI.

Ultimately the strength of Vygotsky’s learning theory stands or falls on the idea that learning is fundamentally a socially mediated and constructed activity. Psychology becomes sociology as all psychological phenomena are seen as social constructs. Vygotsky's theory does not propose distinct developmental stages, like Piaget, but instead emphasizes the role of social interaction and cultural context in cognitive development. He believed that social interaction plays a critical role in children's cognitive development and argued that children learn through interactions with more knowledgeable individuals, who provide guidance and support.

Generative AI

This is exactly what ChatGPT4 does, in general, but also in a more formal teaching experiences as in Khan Academies implementation, Duolingo and other second level implementations of Generative AI. It provides the ‘knowledgeable other’. In fact, this ‘knowledgeable other’ is better than any one teacher as it covers all subjects, at different levels, personalised, is available 365/24/7, is endlessly patient, polite, encouraging and friendly.

Mediation

The cardinal idea in Vygotsky’s psychology of learning is that knowledge is constructed through mediation, yet it is not entirely clear what mediation entails and what he means by the ‘tools’ he refers to as mediators. In many contexts, it simply seems like a synonym for discussion between teacher and learner. However he does focus on being aware of the learner’s needs, so that they can ‘construct’ their own learning experience and changes the focus of teaching towards guidance and facilitation, as learners are not so much ‘educated’ by teachers as helped to construct their own meaning and learning.

This is exactly what ChatGPT4 does as a ‘tool’. It mediates through dialogue and allows the learner to construct their own sense and meaning by driving the learning process through dialogue. It uses language, the key form of learning and social development for Vygotsky, to patiently go at the learners own pace, level and even identify mistakes. It can keep us in a useful Zone of Proximal Development, as the process of dialogue captures what has been said to guide what should be said next. Language is a form of action, where thought essentially involves manipulation of internalised language, and so can be seen as a form of inner action.

Tools

He often uses the word ‘tool’ which refers to any external artifact, symbol, or sign that individuals use to help them think, problem-solve and learn. Tools can be physical objects, as well as cultural and psychological tools. Tools help individuals interact with the world and transform their mental processes. They bridge the gap between a person's current cognitive abilities and their potential for higher-level thinking.

Cultural tools are the external artifacts and signs that are created and shared within a specific cultural context. Examples of cultural tools include writing systems, books, calculators, maps, computers, and language itself. He most likely would have included Generative AI as a useful tool for learning. Vygotsky also identified psychological tools, which are internalized cultural tools that become part of an individual's cognitive processes. Psychological tools include strategies, problem-solving techniques, mnemonic devices, and other mental processes that individuals acquire through social interaction and cultural learning.

Conclusion

Language shapes thought and therefore is intelligence. Both Wittgenstein and Vygotsky had this insight, that language is not an emergent quality of intelligence but is intelligence itself. This explains what LLMs are so powerful. Intelligence is embodied in language and we learn from language. If they are right, generative AI, using written or spoken language will prove to be the most powerful form of learning technology we have ever seen, as they are congruent with how we learn.

Wednesday, February 05, 2020

Vygotsky (1896-1934) - Social constructivism... Oft-quoted, rarely read...

Social constructivism

Mediation

Language and learning

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)

Special needs

Play

Influence

The oft-quoted, rarely read Vygotsky appeals to those who see instruction, and teaching, as a necessary condition for learning and sociologists who see social phenomena as the primary determinant factor in learning. As a pre-Chomsky linguist, his theories of language are dated and much of his thought is rooted in now discredited dialectical materialism. For Vygotsky, psychology becomes sociology as all psychological phenomena are seen as social constructs, so he is firmly in the Marxist tradition of learning theory. One could conclude by saying that Vygostsky has become ‘fashionable’ but not as relevant as his reputation would suggest.

Bibliography

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

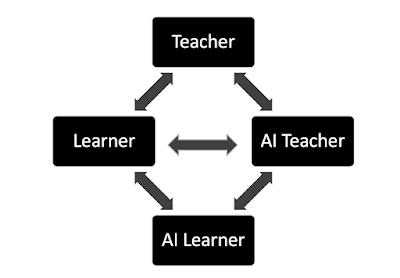

We've just gone from a simple teacher-learner model to a new world of AI teachers - a new pedAIgogy

As new products from OpenAI, Google, Khan Academy, Duolingo and others are launched, with hundreds of millions using them, the learning game has taken a shift. The new pedAIgogy has unleashed a wave of innovation that not only changes our relationship with knowledge away from transfer, search and access, to dialogue and co-creation.

This takes place at several levels. At the level of global culture as LLMs literally take all of our accumulated culture (language, images, audio, video) and mirrors it back to us. It takes place at the level of the individual who can use, talk to and co-create knowledge. This is what Vygotsky talked about with socially constructed learning, mediated by 'tools'.

The learning game used to be simple. We had 'Teachers' and 'Learners'.

Schools, Colleges, Universities and Workplace Learning (L&D) has this as its fundamental model or premise. This is still likely to continue as the model for young children, who have less autonomy in learning. But the world for everyone else has suddenly changed. Our whole relationship with knowledge and skills has changed. The nature of work will also change so how we learn will changed. We need less long-form courses and a more dynamic, personalised approach to learning, one that is also motivating and exciting.That brings us to a fresh and different model, as there are two new kids on the block.

- Human Teacher

- Human Learner

- AI Teacher (such as ChatGPT and its integration into tools such as Khan Academy & Duolingo)

- AI Learner (the AI model trained on a gargantuan amount of data and some human training)

We have moved from Human Teachers and Human Learners, as a diad to AI Teachers and AI Learners as a tetrad. But there is a twist to this tale.

Human Teachers are skilled but those skills tend to be subject specific, they know one topic really well and are not generalists. They also have valuable teaching skills but these level off or plateau.

Learners, however, need to learn more efficiently.

AI learns (see red arrow) and gets exponentially better, AI Teachers therefore get better as they draw upon these improvements from the AI learner.

This means that the balance between teachers and AI changes. Teacher skills plateau, whereas AI Teachers and Learners get better.

AI Teachers get better across ALL subjects. AI Teachers are also available 24/7/365 and are becoming multimodal to deliver speech, text, graphics and video. They also delver dialogue and effortful activity, such as case studies, examples, debate and assessment. We have a new pedagogy based on personal, one-to-one dialogue. This was something researched by Bloom in his paper, The 2 Sigma Problem (1984).

He compared a lecture, lecture with formative feedback and one-to-one tuition. Taking the lecture as the mean, he found an astonishing 84% increase in mastery above the mean fo the formative lecture and 98% increase in mastery for one-to-one tuition.

The final stage, and this is some way off, is the elimination of the human teacher, to provide one-to-one tuition using AI. W are now in that age.

This is an uncomfortable debate but we have now crossed that Rubicon. We can now see that the path to faster, cheaper and more effective learning is through faster, cheaper and smarter technology - that technology, as I've been saying for many years, is AI.

Can you name his two major works? Vygotsky is the most oft-quoted but rarely read learning theorist I know. Let me start by saying I am not an extreme social constructivist but in using ChatGPT3 and 4, I have become more Vygotskian. ChatGPT and Bard are the almost perfect examples of Vygotskian teachers. Let me explain.

This is the cardinal idea in Vygotsky’s psychology of education, that knowledge is constructed through mediation, yet it is not entirely clear what mediation entails and what he means by the ‘tools’ he refers to as mediators. In many contexts, it simply seems like a synonym for discussion between teacher and learner. However he does focus on being aware of the learner’s needs, so that they can ‘construct’ their own learning experience and changes the focus of teaching towards guidance and facilitation, as learners are not so much ‘educated’ by teachers as helped to construct their own meaning and learning.

Vygotsky also prescribes a method of instruction that keeps the learner in the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), an idea that was neither original to him nor even fully developed in his work. The ZPD is the difference between what the learner knows and what the learner is capable of knowing or doing with mediated assistance. To progress, one must interact with peers who are ahead of the game through social interaction, a dialectical process between learner and peer.

Bibliography

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Vygotsky - the Lysenko of learning

Why have learning academics been so keen to resurrect an old Marxist theorist, dress up half-baked sociology and pretend it’s psychology? I’m talking about the oft-quoted, seldom read Vygotsky.

Why have learning academics been so keen to resurrect an old Marxist theorist, dress up half-baked sociology and pretend it’s psychology? I’m talking about the oft-quoted, seldom read Vygotsky.Not content with fossilising 50 year old theory from Bloom, Gagne and Kirkpatrick, the learning world digs even deeper into the past to bring back to life a guy who died in 1934!

Having worked my way through 'Thought and Language' and 'Mind in Society' along with several other Vygotsky texts, I'll be damned if I can see what all the fuss is about. He is to the psychology of learning what Lysenko was to genetics. Indeed the parallel with Lysenko is quite apposite. Forgoing the idea of genetics he sees interventionist, social mediation as the sole source of cognitive development. Vygotsky is a sort of ‘tabla rasa’ Lamarkian learning theorist.

Vygotsky’s psychology is clearly rooted in the dialectical historicism of Hegel and Marx. We know this because he repeatedly tell us. His focus on the role of language, and the way it shapes our learning and thought, defines his social psychology and learning theory. Behaviour is shaped by the context of a culture, and schools reflect that culture. He goes further, driving social influence right down to the level of interpersonal interactions. These interpersonal interactions, he thinks, mediate the development of children’s higher mental functions, such as thinking, reasoning, problem solving, memory, and language. He took larger dialectical themes and applied them to interpersonal communication and learning. This is in direct contradiction to almost everything we now know about the mind and its modular structure.

For him, psychology becomes sociology as all psychological phenomena are seen as social constructs. In this respect he reverses Piaget’s position that development comes first and learning second. Vygotsky puts learning before development - asort of social behaviourist. He's simply wrong.

Very specifically he prescribes a method of instruction that keeps the learner in the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). This is the difference between what can be known on one’s own and what can potentially be known. To progress, one must interact with peers who are ahead of the game through social interaction, a dialectical process between learner and peer. This is not theory, it’s a trite observation.

The rarely read Vygotsky appeals to those who see teaching and instruction as a necessary condition for learning – it is NOT. It also appeals to sociologists who see culture as a the determinant factor in all learning – it is NOT . As a pre-Chomskian linguist, his theories of language are dated and still rooted in now discredited dialectical materialism.

Sorry - gone on a bit here - but soviet sociology is not psychology.

Thursday, November 21, 2013

10 reasons why I am NOT a Social Constructivist

Although Karl Marx wrote little on educational theory, his

influence on learning theory and practice has been profound. In The Communist

manifesto Marx states that education has a ‘social’ context, which is both

direct and indirect, ‘And your education! Is not that also social, and

determined by the social conditions under which you educate, by the

intervention direct or indirect, of society’. It was this idea that

underpinned the entire communist world’s view of learning in the 20th century,

especially through Marxist theorists such as Gramsci and Althusser. In Soviet

Russia and its satellite states education was remoulded around political aims

and when the Cultural Revolution in China between 1949 and 1966 was unleashed,

it had devastating consequences, the nadir coming with Pol Pot and the complete eradication of teachers and schools. Interestingly, when it came to re-education, Marxists states reverted to direct, didactic instruction. To this day Marxism, to a degree, persists

in educational and learning theory, most notably in Gramsci, Althusser and the

‘social’ constructivism of Piaget, Vygotsky and Bruner.

Although Karl Marx wrote little on educational theory, his

influence on learning theory and practice has been profound. In The Communist

manifesto Marx states that education has a ‘social’ context, which is both

direct and indirect, ‘And your education! Is not that also social, and

determined by the social conditions under which you educate, by the

intervention direct or indirect, of society’. It was this idea that

underpinned the entire communist world’s view of learning in the 20th century,

especially through Marxist theorists such as Gramsci and Althusser. In Soviet

Russia and its satellite states education was remoulded around political aims

and when the Cultural Revolution in China between 1949 and 1966 was unleashed,

it had devastating consequences, the nadir coming with Pol Pot and the complete eradication of teachers and schools. Interestingly, when it came to re-education, Marxists states reverted to direct, didactic instruction. To this day Marxism, to a degree, persists

in educational and learning theory, most notably in Gramsci, Althusser and the

‘social’ constructivism of Piaget, Vygotsky and Bruner. Jean Piaget claimed that cognitive development proceeds in

four genetically determined stages, and that they always follow the same order.

This theory of child development, he called ‘genetic epistemology’, and it saw

the minds of children as very different from those of adults. Importantly, this

perception must be taken into account in teaching and learning. Big problem –

he got it mostly wrong. His famous four ‘ages and stages’ developmental model

has been fairly well demolished. How did he get it so wrong? Well, like Freud,

he was no scientist. First, he used his own three children (or others from

wealthy, professional families) and not objective or multiple observers to

eliminate observational bias. Second, he often repeated a statement if the

child’s answer did not conform to his experimental expectation. Third, the

data and analysis lacked rigour, making most of his supposed studies next to

useless. So, he led children towards the answers he wanted, didn’t isolate the

tested variables, used his own children, and was extremely vague on his

concepts. What's worrying is the fact that this Piagean view of child

development, based on 'ages and stages' is still widely believed, despite being

wrong. This leads to misguided teaching methods. Education and training is

still soaked in this dated theory. However, on the whole, his sensitivity to

age and cognitive development did lead to a more measured and appropriate use of

educational techniques that matched the true cognitive capabilities of

children.

Jean Piaget claimed that cognitive development proceeds in

four genetically determined stages, and that they always follow the same order.

This theory of child development, he called ‘genetic epistemology’, and it saw

the minds of children as very different from those of adults. Importantly, this

perception must be taken into account in teaching and learning. Big problem –

he got it mostly wrong. His famous four ‘ages and stages’ developmental model

has been fairly well demolished. How did he get it so wrong? Well, like Freud,

he was no scientist. First, he used his own three children (or others from

wealthy, professional families) and not objective or multiple observers to

eliminate observational bias. Second, he often repeated a statement if the

child’s answer did not conform to his experimental expectation. Third, the

data and analysis lacked rigour, making most of his supposed studies next to

useless. So, he led children towards the answers he wanted, didn’t isolate the

tested variables, used his own children, and was extremely vague on his

concepts. What's worrying is the fact that this Piagean view of child

development, based on 'ages and stages' is still widely believed, despite being

wrong. This leads to misguided teaching methods. Education and training is

still soaked in this dated theory. However, on the whole, his sensitivity to

age and cognitive development did lead to a more measured and appropriate use of

educational techniques that matched the true cognitive capabilities of

children.10. Groupthink

I often ask what people who mention social contsructivism, what it emans to them, and almost universally get vague answers. I then ask for names, and often Vygotsky is mentioned. I then ask what Vygotsky texts they have read. At this point there's often a blank stare - they can rarely mention a title. My point is that social constructivism is itself a social construct, often just a phrase, certainly often a piece of groupthink, rarely thought through. It gets perpetuated in teacher training and many other contentxs as a universal truth - which it is not. It is a theory that on first hearing, flatters teachers as the primary 'mediators' in learning. In other words, it is a function of confirmation bias.

Monday, April 02, 2012

Bruner (1915-2016 ) constructivist scaffolder

Bruner, like Vygotsky, focuses on the social and

cultural aspects of learning but can also be seen as a cognitive psychologist. He suggests that people learn with meaning and

personal significance in mind, not just through attention to the facts.

Knowledge and memory are therefore constructed. Learning must therefore be a

process of discovery where learners build their own knowledge, with the active

dialogue of teachers, building on their existing knowledge. However, social

constructivism is sometimes in danger of producing a vocabulary that is used

without much reference to actual practice and detail.

Bruner, like Vygotsky, focuses on the social and

cultural aspects of learning but can also be seen as a cognitive psychologist. He suggests that people learn with meaning and

personal significance in mind, not just through attention to the facts.

Knowledge and memory are therefore constructed. Learning must therefore be a

process of discovery where learners build their own knowledge, with the active

dialogue of teachers, building on their existing knowledge. However, social

constructivism is sometimes in danger of producing a vocabulary that is used

without much reference to actual practice and detail.